WW1 War Loan

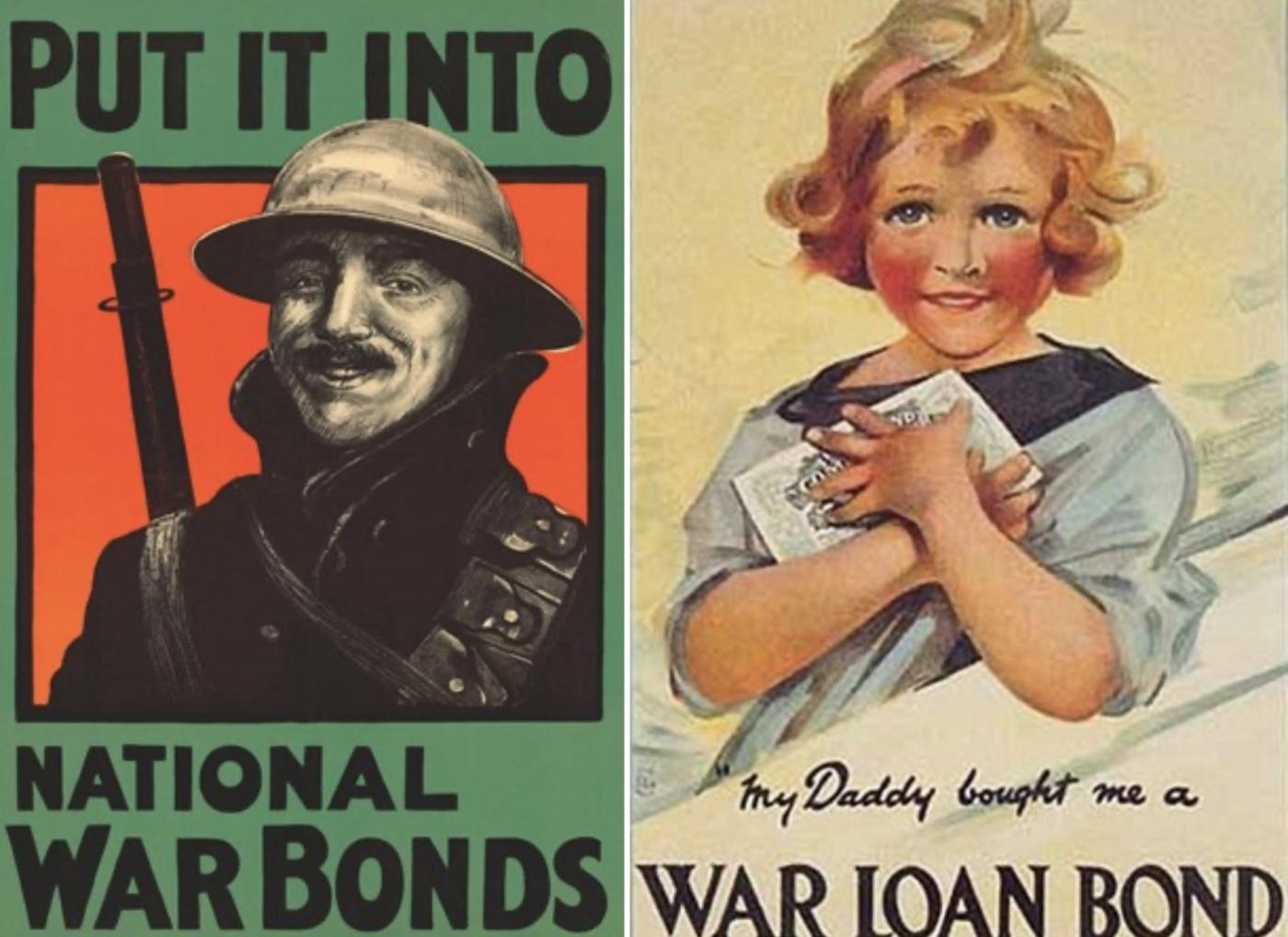

During the First World War, the British government faced unprecedented financial demands to support its vast military operations, both at home and across the world. Traditional methods of funding through taxation alone were insufficient, leading to the need for large-scale borrowing from the public. One of the primary ways Britain raised money was through the issuance of War Loans and War Bonds, which became essential instruments in financing the conflict. These schemes involved the government borrowing money from individuals, businesses, and institutions with the promise of repayment after a set period, along with interest. The first major War Loan was issued in November 1914, shortly after the outbreak of the war. This initial offer promised an interest rate of 3.5% and aimed to raise £350 million, an enormous sum at the time. The campaign was largely successful, supported by extensive government propaganda and patriotic appeals urging citizens to lend their savings to support the war effort. As the war intensified and the financial strain grew, further loans were issued, including the better-known 1917 War Loan, which offered a 5% interest rate and was open-ended, allowing the government to keep drawing funds. These loans were heavily promoted through posters, newspaper advertisements, public speeches, and even door-to-door canvassing. The government framed the act of purchasing War Bonds or subscribing to a War Loan as a patriotic duty, with slogans like “Lend to Defend the Right to be Free” and “If You Cannot Fight, You Can Help by Lending.” The effort was bolstered by a well-coordinated publicity machine that presented lending as a form of national service. Even schoolchildren were encouraged to participate through War Savings Certificates, making the appeal cross-generational. War Bonds were usually short-term securities with lower yields than the larger War Loans but were easier for ordinary citizens to purchase. They were often sold in small denominations, allowing those of modest means to contribute. The introduction of War Savings Committees throughout the country helped organize local efforts, with banks, post offices, and employers playing active roles in facilitating purchases. Beyond private citizens, major financial institutions, companies, and even local authorities invested heavily in these schemes, sometimes under social or political pressure. The financial strategy not only allowed the government to maintain its war expenditure but also helped control inflation by drawing excess money out of circulation. However, the loans came with long-term consequences. After the war, the debt burden from these borrowings contributed to Britain’s interwar economic struggles. Some of the loans, such as the 5% War Loan of 1917, were not fully repaid until nearly a century later, with a final repayment made in 2015. Despite this, the war financing campaign is remembered as one of the most ambitious and wide-reaching efforts in British financial history, an operation that combined economic necessity with national unity and mass participation.

Do