Words Are Weapons

Long before radio, social media, or even reliable loudspeakers, armies discovered a simple truth: a sheet of paper can travel further than a soldier, slip past a front line, and get inside someone’s head. Leaflet drops are one of the oldest tools of psychological warfare. They are designed to influence how people think, what they believe is true, and which choices feel safest or most inevitable. Sometimes the aim is direct persuasion, sometimes it is doubt, fear, reassurance, or confusion. Very often it is simply to make sure the enemy knows they are being watched and addressed personally.

The idea began before powered flight. In the late nineteenth century, military planners experimented with balloons to carry messages across defended territory. If a balloon could deliver mail or news, it could just as easily deliver propaganda. Early leaflet use appeared in conflicts such as the Franco-Prussian War, where balloons were among the few ways to bypass blockades and fixed defenses. Even at this early stage, the psychological value was clear: messages arriving from the sky felt intrusive and unsettling, and they could reach people no army could physically reach.

The First World War turned leaflet dropping into a systematic military practice. Aircraft made it possible to deliver propaganda repeatedly and over wide areas. From about 1915 onwards, planes regularly carried bundles of leaflets instead of, or alongside, bombs. These were aimed at soldiers in trenches and civilians behind the lines. The messages promised food, safety, or humane treatment if troops surrendered, highlighted enemy casualties, or spread bad news that censorship kept from the public. Toward the end of the war, unmanned balloons were used extensively to scatter leaflets deep into enemy territory. By the final year of the conflict, tens of millions of leaflets were being released in single campaigns, showing how quickly the practice had scaled up once its usefulness was recognized.

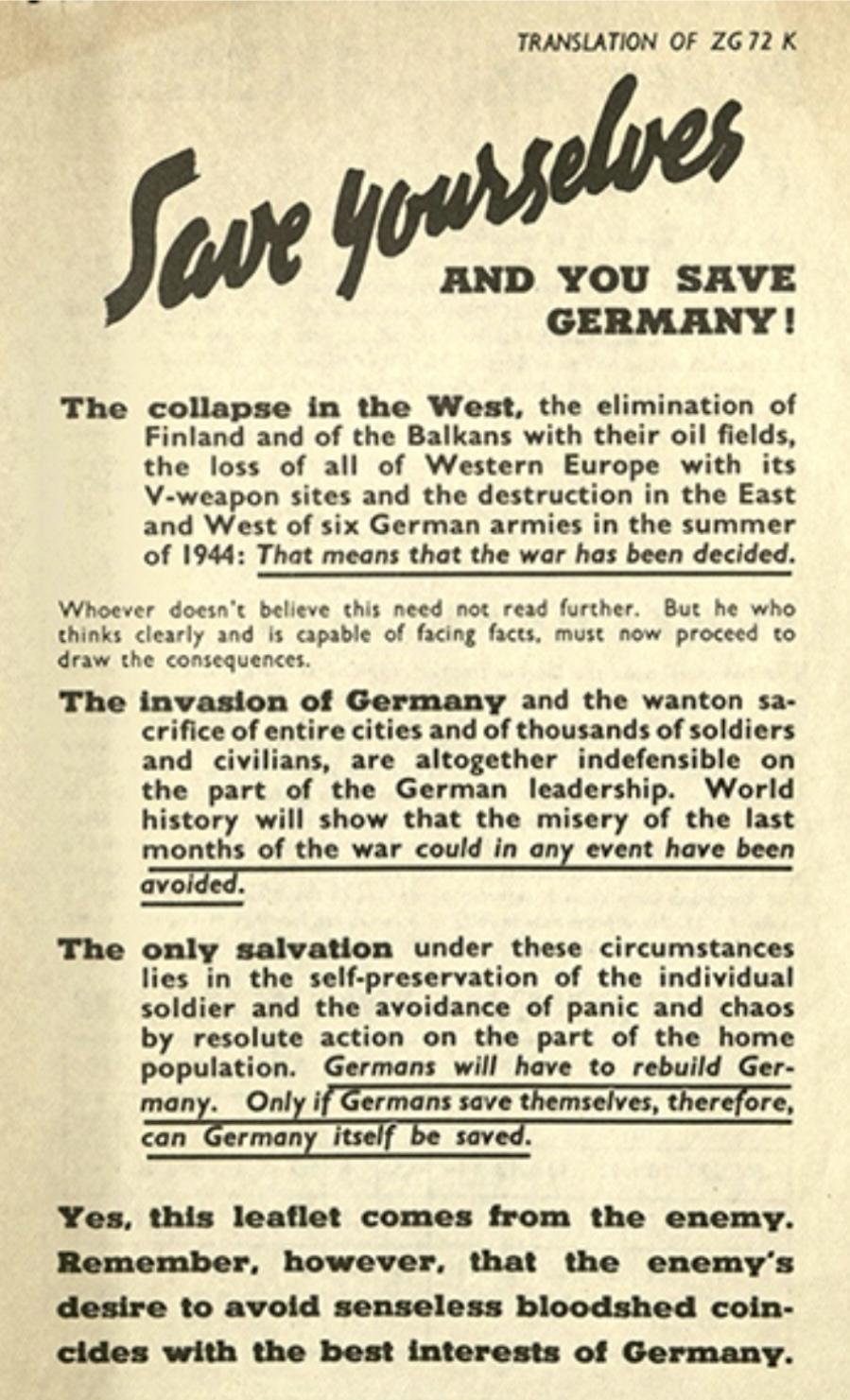

Between the two world wars, leaflet propaganda became more refined. Militaries learned that effectiveness depended less on slogans and more on understanding the audience. Language, dialect, humor, and cultural references mattered. Leaflets began to fall into recognizable types. Some acted as safe conduct passes, meant to be carried by surrendering soldiers to reduce the risk of being shot. Others provided news the enemy tried to hide, instructions on how to avoid danger, or messages designed to create resentment between ordinary soldiers and their officers. Civilian-focused leaflets aimed to weaken morale, slow production, or encourage people to pressure governments and armies from within.

The Second World War marked the peak of leaflet production in sheer scale. Printing presses ran constantly, and bombers were routinely dispatched on missions whose primary payload was paper. By the end of the war, Allied forces alone had dropped billions of leaflets across Europe. Some estimates put the figure at around six billion. The volume was staggering, but so was the variety. Leaflets were printed in many languages and tailored to specific regions, units, and moments in the fighting. The famous safe conduct passes were especially important, because they gave soldiers a clear and concrete method to surrender without panic. In many cases, surrender rates increased sharply after such leaflets were distributed, not because the messages were inspirational, but because they reduced uncertainty in terrifying circumstances.

After 1945, leaflet campaigns did not fade away. Instead, they became more closely measured and analyzed. During the Korean War, leaflet use expanded even further. Over the course of the conflict, more than two billion leaflets were produced and distributed. Military planners tracked printing numbers, drop locations, and even attempted to measure how enemy behavior changed afterward. One lesson became increasingly obvious: sheer quantity did not guarantee success. Leaflets worked best when their message matched what people could already see with their own eyes. When propaganda contradicted lived reality, it was ignored or mocked.

The Vietnam War saw another dramatic escalation. Over several years, billions of leaflets were dropped across Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia. The United States alone printed well over six billion. What made this period distinctive was the extreme targeting. Hundreds of different leaflet designs were created, many aimed at very narrow audiences such as local villagers, specific military units, or fighters considering defection. A major focus was encouraging defections by emphasizing safety, family reunification, and decent treatment. Again, the psychology was less about ideology and more about making one option feel safer than the alternative.

By the late twentieth century, leaflet drops had become a standard feature of modern warfare. During the 1991 Gulf War, tens of millions of leaflets were dropped in just a few weeks. They warned troops about impending attacks, explained how to surrender, and instructed civilians to stay away from military targets. The speed of modern campaigns made leaflets especially useful: they could rapidly tell large populations what to do right now, without relying on electricity, radios, or trust in official broadcasts.

This pattern continued into conflicts in the Balkans, Afghanistan, and Iraq. Short wars often produced enormous leaflet numbers in compressed timeframes, sometimes exceeding one hundred million leaflets in only a couple of months. In Iraq in 2003, tens of millions were dropped even before major combat began, followed by many more during the invasion itself. Leaflets were used to prepare the psychological environment in advance, shaping expectations before the first shots were fired.

Psychologically, leaflets work by shifting mental frames rather than winning arguments. War narrows people’s thinking to survival, loyalty, and fear of consequences. Effective leaflets speak directly to those pressures. They reduce uncertainty, offer clear instructions, promise safety, highlight isolation, or suggest that resistance is pointless. They often separate soldiers from their leaders, implying betrayal or incompetence at the top while offering an honorable way out at the bottom. Even when they fail to persuade, leaflets can still disrupt, forcing armies to spend time confiscating them, punishing possession, and countering their messages.

There is also a moral complexity to leaflet warfare. Some leaflets save lives by warning civilians away from danger. Others deliberately frighten populations or spread false information. Because leaflets are physical objects, they can be kept and shared, turning promises into evidence. This permanence gives them power, especially when they promise humane treatment or safety and those promises are kept.

Despite the rise of digital communication, leaflets have not disappeared. In some regions, they have returned to balloons, precisely because balloons can cross borders quietly and reach places where broadcasts are blocked. The technology may be old, but the psychological logic remains the same.