Jewish Commandos

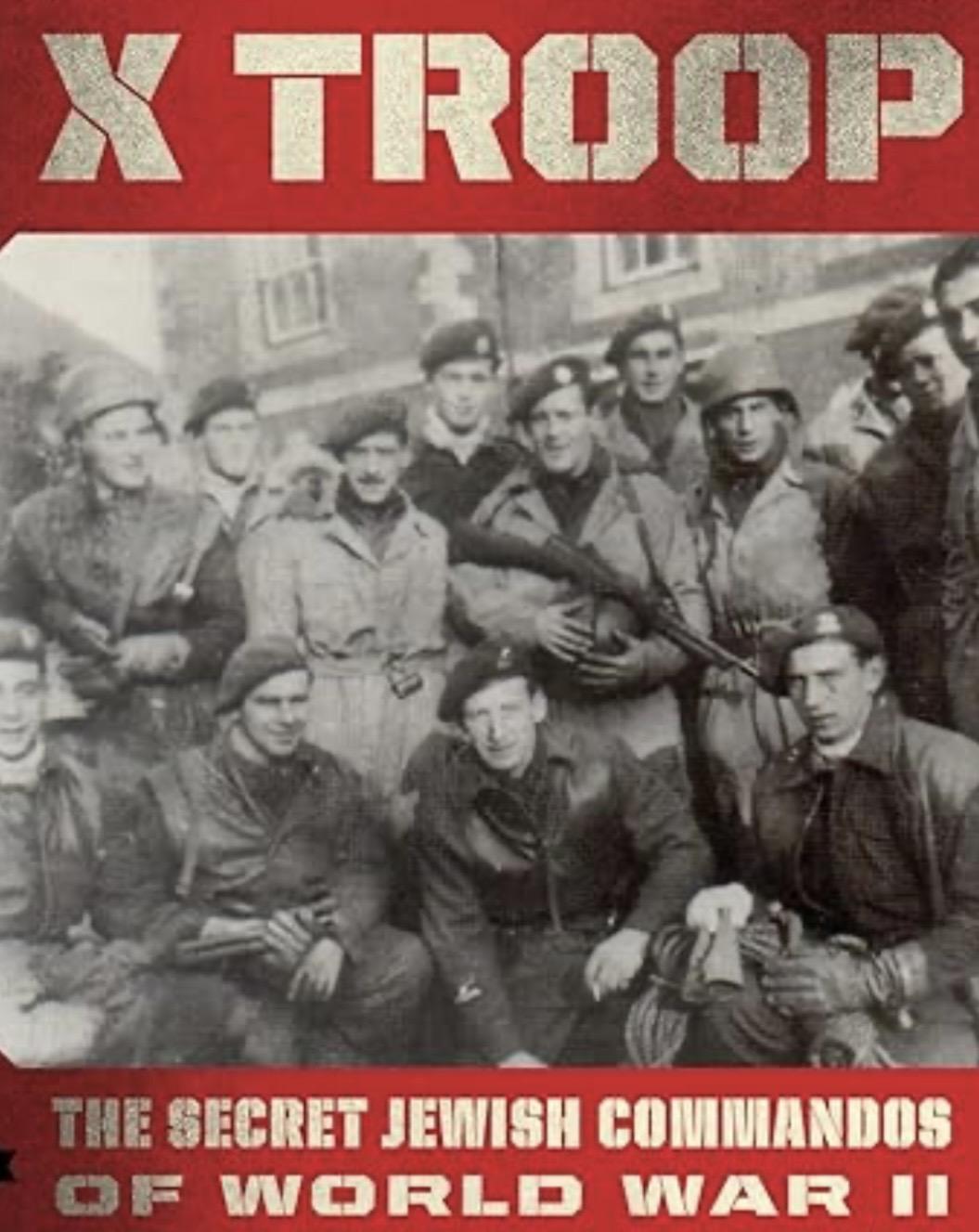

X Troop was one of the most unusual and morally charged units created by Britain during the Second World War. It was a small group of Jewish soldiers, most of them refugees from Nazi Germany and Austria, who volunteered to fight the regime that had destroyed their families and stripped them of their citizenship. Officially, they were designated 3 Troop of No. 10 (Inter-Allied) Commando, but within the army they were usually referred to simply as X Troop, a deliberately vague title chosen to conceal their identity and purpose.

The men who formed X Troop had fled Europe in the 1930s as antisemitic laws hardened into state violence. Many arrived in Britain as teenagers or young adults, often alone, having left parents and siblings behind. When war broke out, some were initially treated as “enemy aliens” because of their German or Austrian birth. Over time, British intelligence and the army came to realise that these men represented an extraordinary and largely untapped resource. They spoke flawless German, understood German military culture, and knew the mentality of the enemy from the inside. Just as importantly, they had a fierce personal motivation to defeat Nazism.

The idea of forming a dedicated troop of German-speaking Jewish soldiers emerged as Britain expanded its special forces and commando capability. This thinking was strongly encouraged by Lord Louis Mountbatten, who believed that modern warfare required imagination, speed, and the intelligent use of specialist knowledge. Within the framework of No. 10 Commando, which already consisted of foreign nationals fighting for Britain, it made sense to group these Jewish volunteers together for training, security, and operational effectiveness. Their Jewish background was kept officially secret. Many were given Anglicised names, both to protect surviving relatives in occupied Europe and to reduce the risk of immediate execution if captured.

Selection for X Troop was ruthless. Language ability alone was not enough. These men were required to pass the same demanding commando training as British-born volunteers, including endurance marches, amphibious assaults, weapons handling, and close-quarters combat. Those who succeeded proved that they were not simply interpreters in uniform, but fully qualified commandos. As a result, members of X Troop were frequently attached to front-line units, particularly those operating within 3 Commando Brigade, where their skills could be used directly in combat.

Operationally, X Troop did not function as a separate strike force. Instead, its men were embedded within commando operations across northwest Europe. During the Normandy landings and the fighting that followed, they landed with assault troops, interrogated prisoners under fire, translated captured documents, and identified enemy units within minutes of contact. Their ability to recognise accents, slang, and unit insignia often exposed German deception or prevented ambushes. In fast-moving operations, this kind of intelligence could mean the difference between success and disaster.

As the Allied advance continued through France, Belgium, and the Netherlands, members of X Troop were increasingly used to screen civilians, refugees, and prisoners. Europe was filled with displaced people, collaborators, and German agents attempting to escape capture. The men of X Troop could often tell, from a single sentence or mannerism, whether someone was who they claimed to be. They also assisted in liaison with resistance groups and in securing key infrastructure before German forces could destroy it.

The danger they faced was extreme. If captured by the Germans, these men would not have been treated as ordinary prisoners of war. As German-born Jews fighting in Allied uniform, they were viewed as traitors and racial enemies. Many were aware that capture would almost certainly mean torture and execution. Some made private agreements never to surrender alive. Despite this, they continued to serve on the front line, disciplined and professional, rarely allowing personal hatred to interfere with military judgement.

After the war, X Troop quietly disappeared from public view. Official secrecy, combined with the survivors’ reluctance to revisit traumatic memories, meant that their story was largely forgotten for decades. Britain celebrated victory, but paid little attention to the refugees who had helped make it possible. Only later did historians begin to recognise the significance of what these men had achieved.