Tyre Rationing

On 26 December, in the tense days following the United States’ entry into the Second World War, the federal Office of Price Administration announced the introduction of tyre and rubber rationing as an essential measure to support the war effort. The decision reflected a sudden strategic reality: rubber, though commonplace in peacetime America, had become one of the most critical and vulnerable materials of modern warfare. Tyres were indispensable not only for civilian transport but for trucks, tanks, aircraft, and virtually every branch of military logistics. With overseas supply lines cut or threatened, conservation at home became a matter of national security.

The Office of Price Administration, commonly known as the OPA, had been created earlier in 1941 to prevent inflation and shortages caused by wartime pressures. Its remit was broad and powerful. The agency was responsible for setting price ceilings, preventing hoarding, and later administering rationing systems for scarce goods. After Pearl Harbor, its role expanded rapidly. The rubber crisis brought the OPA to the forefront of daily American life, as tyres were among the first major civilian items to come under strict federal control.

Rubber was particularly vulnerable because the United States relied heavily on imports from Southeast Asia, especially British Malaya and the Dutch East Indies. When Japanese forces swept through these regions in early 1942, more than 90 percent of America’s natural rubber supply was effectively cut off. Even before those territories fully fell, planners understood what was coming. The 26 December announcement was therefore both urgent and preventative, aiming to stretch existing stocks for as long as possible while alternative solutions were developed.

The rationing plan focused not only on limiting the sale of new tyres but on reducing wear on those already in use. One of the earliest and most striking measures was the call for motorists to limit or abandon non-essential driving. The slogan “When you ride alone, you ride with Hitler” soon became one of the most memorable propaganda messages of the war, linking everyday behaviour directly to enemy advantage. Though not exclusively an OPA slogan, it worked hand in hand with tyre rationing by discouraging unnecessary mileage and encouraging carpooling.

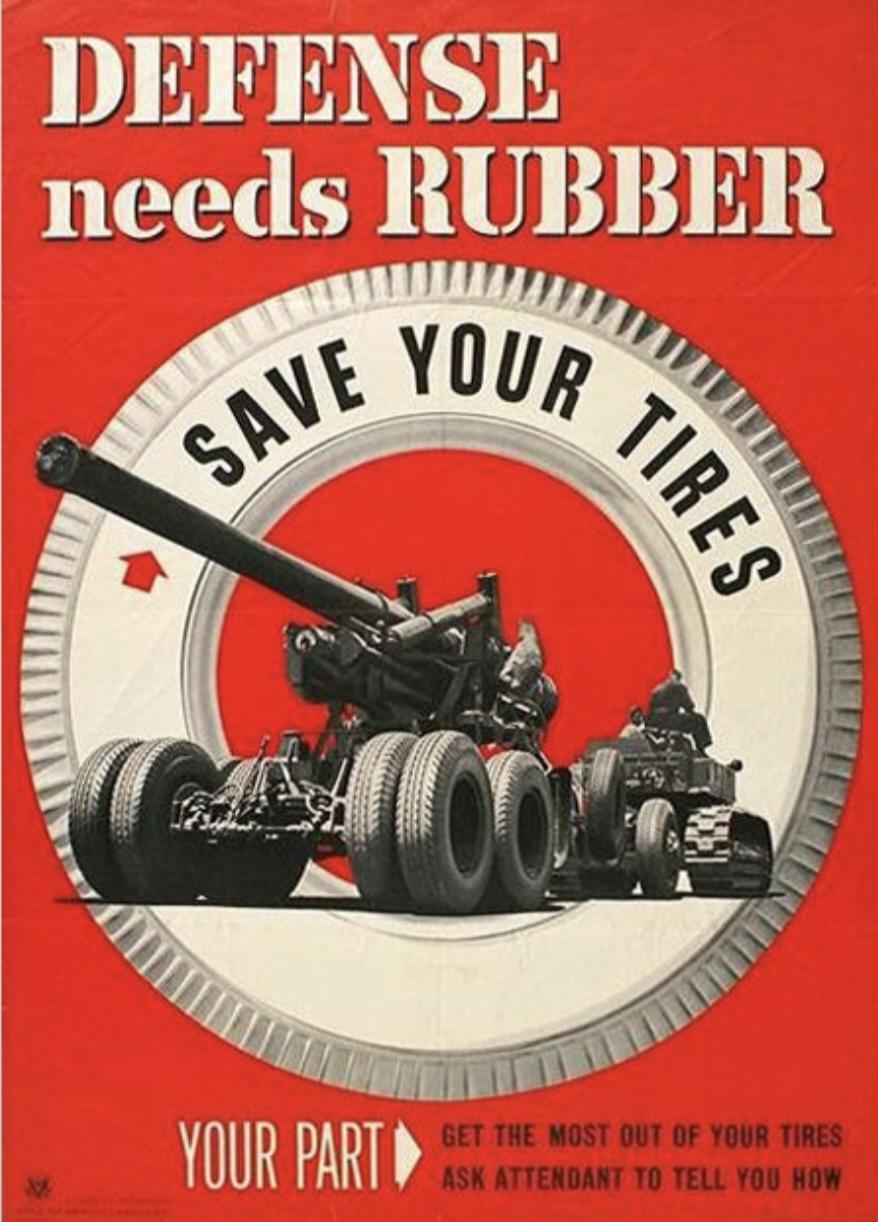

Advertising and public messaging were central to the OPA’s approach. The agency used newspapers, radio broadcasts, posters, and pamphlets to explain the rubber shortage and to persuade the public that compliance was patriotic rather than punitive. Advertisements often featured stark imagery of military vehicles immobilised for lack of tyres, contrasted with civilian cars idling uselessly on empty roads. The message was simple and emotional: every mile driven unnecessarily shortened the life of a tyre that might otherwise support a soldier overseas.

Implementation of tyre rationing was deliberately bureaucratic, designed to prevent abuse while maintaining a sense of fairness. Motorists were required to register their vehicles, after which tyres were classified according to condition. Poorly maintained or excessively worn tyres could disqualify a driver from receiving replacements, an incentive that encouraged better upkeep. New tyres could only be purchased with official ration certificates, issued primarily to those whose driving was deemed essential, such as doctors, farmers, delivery drivers, and defence workers.

To enforce the system, the OPA relied on a network of local rationing boards staffed largely by volunteers. These boards reviewed applications, issued certificates, and served as the human face of federal control. Their decisions could be strict and sometimes unpopular, but they also allowed rationing to reflect local needs. In rural areas, for example, farmers were often prioritised because their vehicles were critical to food production, itself a key part of the war effort.

An interesting and lesser-known aspect of tyre rationing was how it reshaped American habits and infrastructure. Public transport use increased, bicycles enjoyed a resurgence, and many families simply stayed closer to home. Tyre repair, retreading, and patching became routine, with garages encouraged to extend the life of existing rubber rather than sell replacements. The phrase “use it up, wear it out, make it do, or do without” became an unofficial motto of the home front.

The rubber crisis also accelerated scientific and industrial innovation. While rationing conserved supplies, the federal government poured resources into developing synthetic rubber. By the end of the war, the United States had built a massive synthetic rubber industry virtually from scratch, a direct response to the shortages that made the December 26 decision so necessary. In this sense, tyre rationing was not just a temporary hardship but a catalyst for long-term industrial change.

The introduction of tyre and rubber rationing by the Office of Price Administration marked one of the first moments when American civilians felt the war intrude directly into everyday life. It demonstrated how total war blurred the line between front lines and home front, turning routine activities like driving into acts with national consequences. Through regulation, persuasion, and a powerful appeal to shared sacrifice, the OPA transformed a looming material crisis into a collective effort, reminding Americans that victory depended as much on restraint at home as on force abroad.