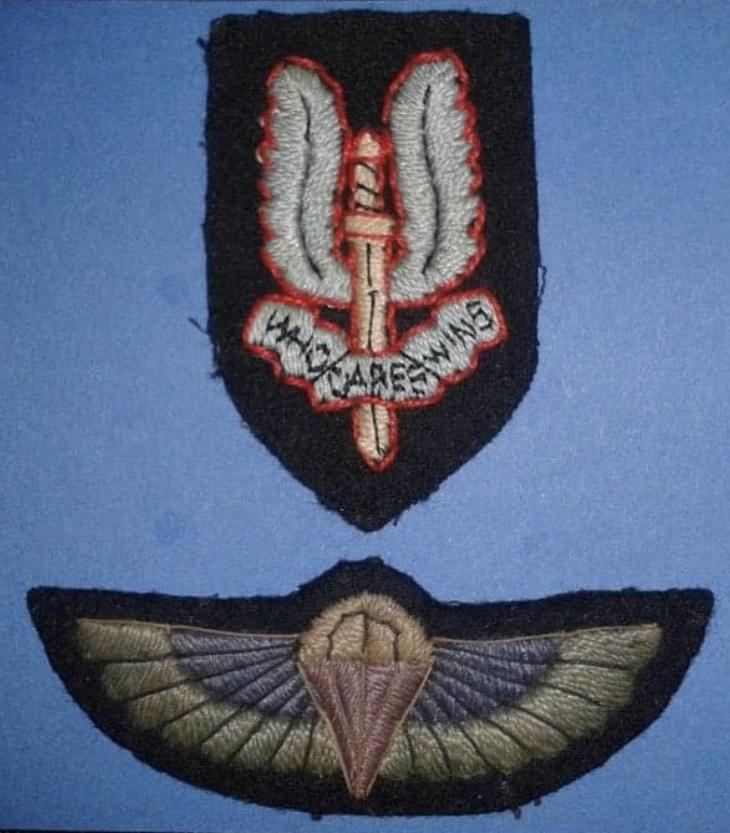

SAS Cap Badge

The cap badge of the Special Air Service is one of the most recognisable military insignia to emerge from the Second World War, and its design can be traced very precisely to the unit’s chaotic and improvised beginnings in the Western Desert in 1941. The badge was conceived shortly after the formation of “L Detachment, Special Air Service Brigade”, when its founder, David Stirling, realised that a distinctive emblem was essential if his new force was to develop a sense of identity separate from conventional units.

The actual design work was carried out by Bob Tait, a Scottish artist and illustrator who was serving in the Middle East at the time. Tait had known Stirling before the war and was brought into the project because Stirling wanted something symbolic rather than heraldic in the traditional British Army sense. Stirling’s instructions were simple but specific: the badge should suggest stealth, speed, independence, and a connection to Britain without copying existing regimental devices.

Tait produced the now-famous winged dagger, officially described as a flaming sword but more commonly associated with Excalibur, the legendary sword of King Arthur. The dagger symbolised sudden violence and precision, while the wings represented airborne insertion and freedom of movement behind enemy lines. The choice of Excalibur was deliberate, reflecting Stirling’s romantic belief that the SAS should see itself as a modern band of warrior-knights operating by initiative rather than rigid doctrine. The flames along the blade were intended to convey destruction and relentless attack rather than chivalry.

The badge was first produced locally in Cairo using whatever materials were available, and early examples varied considerably in size, finish, and quality. Some were crudely cast, others hand-cut, and many were privately purchased rather than officially issued. This lack of standardisation mirrored the early SAS itself, which was initially viewed with suspicion by conventional commanders and existed largely outside normal administrative systems. Despite this, the badge quickly became a powerful symbol within the unit, worn with pride and guarded fiercely as a mark of belonging.

The question of SAS wings during the Second World War is more complex. Contrary to popular belief, there were no unique SAS parachute wings officially designed or issued during the war itself. SAS personnel who qualified as parachutists wore standard British Army or Royal Air Force parachute wings, depending on their training and parent arm. Many early SAS men completed RAF parachute courses and therefore wore RAF-style wings, while others trained under Army schemes and wore the Army parachutist badge.

This situation reflected the unconventional nature of the wartime SAS. It was not a formally recognised regiment for much of the war, and uniform regulations were applied loosely, if at all. Photographs from North Africa, Sicily, and France show SAS soldiers wearing a wide mix of insignia, or sometimes none at all, particularly when operating behind enemy lines where concealment mattered more than appearance.

The distinctive SAS wings familiar today were a post-war development, created when the regiment was reconstituted and formalised in the late 1940s and early 1950s. These wings drew inspiration from wartime experience but were not worn during combat operations in the Second World War. Their later introduction often leads to confusion, with modern imagery retroactively applied to wartime SAS soldiers who never actually wore them.

An interesting aspect of both the badge and the later wings is how closely they are tied to the personality of David Stirling. Stirling was not interested in military tradition for its own sake, but he understood the psychological value of symbols. The winged dagger became a rallying point for men operating in extreme isolation, often in small groups far from friendly forces, and it helped foster the intense loyalty and self-belief that became hallmarks of the SAS.

Another notable detail is that the badge was never meant to be decorative. Early SAS doctrine emphasised anonymity and deception, and the badge was as much an internal symbol as an external one. In some operations, men removed or concealed it entirely. Its power lay not in public recognition but in what it meant to those who had earned the right to wear it.

By the end of the war, the SAS cap badge had already achieved a status far beyond its humble origins as a sketch made in Cairo.