Proximity charge fuse ordnance

The proximity (VT, or Variable Time) charge fuze was one of the quiet revolutions of the Second World War, a small electronic device that changed the lethality of artillery and anti-aircraft fire almost overnight. It was introduced late in the war, first at sea against Japanese aircraft, then over Europe, and finally in massed artillery form during the Battle of the Bulge, where its debut on land was so devastating that German commanders believed the Americans had developed a new kind of chemical or fragmentation shell.

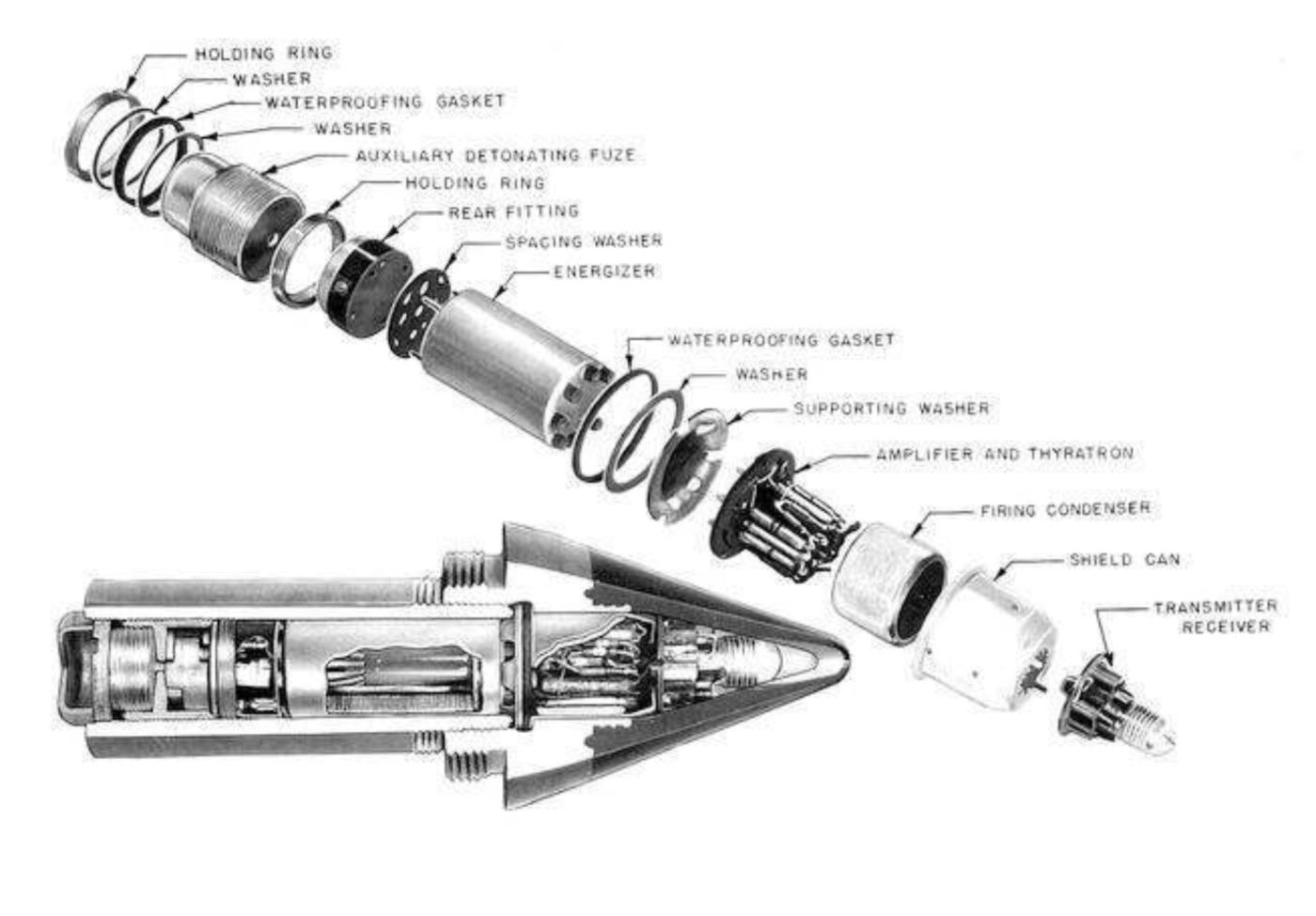

The fuze was born from the work of American physicist Merle Tuve and his team at the Carnegie Institution’s Department of Terrestrial Magnetism, working under the Office of Scientific Research and Development. Under contract, Section T refined the concept of a small, rugged radio device that could survive the violent acceleration of firing and still function reliably in flight. The principle was simple but revolutionary: instead of relying on timed or impact detonations, the fuze sent out a miniature radio signal that reflected off a nearby aircraft, tree line, or ground surface. When the returning signal reached a specific amplitude—meaning the shell was very close to the target—the fuze triggered detonation. This allowed shells to burst at the most destructive point, showering targets with fragments rather than burying their lethal effect in the soil.

Turning this delicate electronics package into something that could be mass-produced was a major challenge. The manufacturing effort involved a consortium of American firms including Crosley Corporation, Eastman Kodak, General Electric, Emerson Radio, RCA, and Sylvania, among others. The assembly required miniature vacuum tubes, tiny batteries, and careful production tolerances. These tubes had to be tough enough to endure forces of more than 20,000 g at firing, an engineering feat of its own. By the end of the war roughly 22 million proximity fuzes had been produced, a scale of output that matched the urgency of stopping kamikazes in the Pacific and breaking German defensive concentrations in Europe.

The Battle of the Bulge marked the first large-scale land deployment of the fuze. Artillery units were ordered to use it only when absolutely necessary, as the Allies feared any unexploded fuzes could be recovered and copied. When the German offensive broke out in December 1944, that restriction was lifted. American gunners began firing airburst shells that detonated above advancing infantry, shredding exposed troops and even those who thought they were protected in shallow foxholes. German soldiers frequently reported hearing shells explode before impact, something they were not accustomed to, and the psychological effect was profound. Entire attacks were broken up by bursts that bracketed and blinded units in white-hot fragmentation clouds before they could reach American lines.

In anti-aircraft roles the fuze had already shown its power. Against V-1 flying bombs it raised the kill rate dramatically, allowing guns to destroy more enemy missiles with fewer rounds. At sea, carriers and destroyers suddenly found they could bring down diving aircraft at ranges that previously would have required impossible accuracy. At one point in 1944–45, more Japanese planes were destroyed by naval guns with VT fuzes than by fighters, an almost unthinkable shift given the speed of aircraft.

One of the interesting aspects of the fuze’s development was the secrecy surrounding it. Scientists joked that the fuze was the “one weapon we must not let fall unexploded,” because if the enemy recovered even a single intact unit they could learn the principle. Fortunately for the Allies, none of the land-service fuzes failed in such a way, and when Germany tried to examine naval examples, they often found the internal components destroyed or waterlogged.

Another lesser-known fact is that the fuze helped shorten engagements simply because artillery became far more efficient. Instead of firing long barrages to achieve a destructive effect, a smaller number of shells could achieve airburst patterns that suppressed or eliminated enemy troops instantly. In forests like the Ardennes, where tree bursts were already feared, the proximity fuze turned every shell into a perfectly timed canopy explosion, increasing lethality beyond what German planners expected.

To the soldiers who witnessed its introduction, the proximity fuze appeared almost magical, but its impact was very real: improved anti-aircraft defense, more effective artillery, and a decisive edge in defensive battles. Many historians place it alongside radar, codebreaking, and the atomic bomb as one of the war’s true technological game changers.