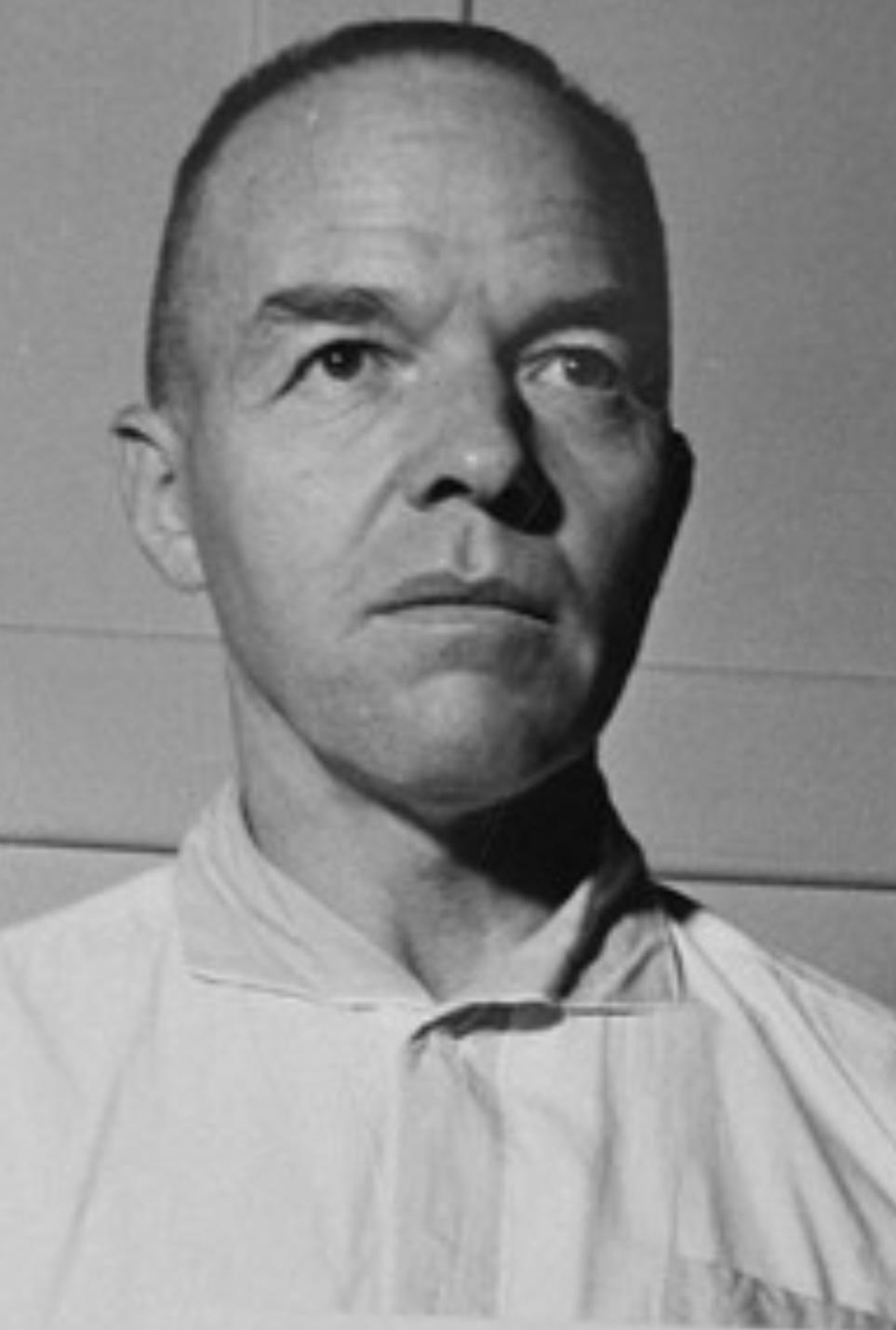

Otto Rasch

Otto Rasch was not a flamboyant ideologue or a crude thug elevated by chaos. He was a trained jurist and administrator who embodied the dangerous fusion of education, obedience, and ideology that allowed genocide to function as routine state policy. As commander of Einsatzgruppe C during the German invasion of the Soviet Union, Rasch bore responsibility for some of the worst mass killings carried out by Nazi mobile murder units.

Otto Rasch was born on 7 December 1891 in Friedrichsruh, in the German Empire. He grew up in a society shaped by militarism and hierarchy and came of age during the First World War, serving as a naval officer. Like many men of his generation, Germany’s defeat left him disoriented and resentful, receptive to nationalist explanations for collapse and humiliation.

After the war Rasch pursued higher education, earning advanced degrees in law and related disciplines. He belonged to a cohort of educated professionals who felt alienated by the instability of the Weimar Republic and drawn toward movements that promised order, authority, and national revival. Unlike many early Nazis who emerged from street violence or paramilitary politics, Rasch’s path was bureaucratic and professional.

He joined the Nazi Party in 1931, before Hitler seized power, and soon entered the SA and then the SS. Once the Nazis took control in 1933, Rasch’s education and administrative competence made him useful. He was appointed to municipal leadership roles, including mayoral positions, where he demonstrated ideological reliability and organizational efficiency. These roles served as stepping stones rather than endpoints.

By the mid-1930s Rasch transitioned fully into the expanding Nazi security apparatus. He moved through the State Police, the Security Police, and the SD, integrating himself into the system that oversaw political repression, surveillance, and the identification of “enemies of the state.” His rise was not marked by dramatic gestures but by steady compliance and effectiveness within an increasingly radicalized bureaucracy.

When Germany invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941, the Nazi leadership deployed the Einsatzgruppen, mobile units tasked with eliminating perceived enemies behind the front lines. In practice, this meant systematic mass murder, especially of Jewish civilians. Rasch was appointed commander of Einsatzgruppe C, which operated primarily in northern and central Ukraine in the wake of Army Group South.

Under his command, Einsatzgruppe C carried out numerous mass shootings in towns, villages, and execution sites across the region. The most infamous atrocity associated with his command was the massacre at Babi Yar near Kyiv in late September 1941, where more than 33,000 Jewish men, women, and children were murdered over two days. Although multiple German police and security formations participated, Rasch was the senior Einsatzgruppen commander in the area and bore command responsibility for the unit’s actions.

Rasch did not design the Einsatzgruppen system or originate its ideological goals. Those directives came from higher authorities in Berlin. His role was to ensure that the system functioned effectively on the ground. One of the most chilling aspects of his leadership was his insistence that officers and men personally participate in shootings. This was not training in a formal sense, but a deliberate method of conditioning. By requiring direct involvement, Rasch helped create shared guilt, reduced resistance, and transformed mass killing into routine duty.

This approach bound the unit together through complicity and normalized extreme violence. Killing was no longer an exceptional act but an expected component of professional conduct. In this way, Rasch helped harden his men psychologically and ensured the continued pace of murder.

Rasch did not personally recruit most of the men under his command. Einsatzgruppen personnel were assigned through central security and police channels. Core members came from the SS, SD, Gestapo, and Criminal Police, many of them educated professionals and career officers rather than untrained extremists. Once deployed, Einsatzgruppe C worked closely with Order Police battalions, Waffen-SS units, and locally recruited auxiliary police in occupied territories. These auxiliaries assisted with roundups, guarding, and shootings, greatly expanding the killing capacity of the unit.

While staffing decisions originated above him, Rasch exercised authority over how these men were used, how often operations occurred, and how fully violence permeated daily routines. His leadership shaped the tempo and intensity of the killings.

After Germany’s defeat, Rasch was arrested and indicted in the postwar Einsatzgruppen Trial, part of the subsequent Nuremberg proceedings aimed at prosecuting those responsible for mass murder in Eastern Europe. However, he never faced a completed trial. Declared medically unfit due to severe physical and mental illness, his case was suspended. He died in custody in 1948, escaping formal judgment and sentence.

Rasch matters not because he was uniquely sadistic or theatrically evil, but because he demonstrates how genocide can be administered by educated, disciplined, and outwardly unremarkable men. His career shows how legal training, bureaucratic competence, and ideological obedience can combine to make mass murder function smoothly. He did not shout slogans or revel publicly in violence. He organized, supervised, and ensured that killing was carried out efficiently and repeatedly. In that quiet efficiency lies the most disturbing lesson of his life.