Operation Crusader

Operation Crusader opened in the pale dawn light of 18 November 1941 in the Western Desert with a violence and breadth of movement that genuinely shocked Erwin Rommel. For weeks before, the Afrika Korps commander had fully convinced himself that the British Eighth Army, worn by losses and timid in his view, could not launch a major offensive before December. The British meanwhile deliberately fed this belief. Radio deception units, dummy lorries and tanks, false supply dumps, and carefully staged non-activity signals traffic all made Rommel believe the main British armour sat around Mersa Matruh far to the east, immobile and resting. In reality General Alan Cunningham had been placed in command of Eighth Army and was preparing three full corps to roll west at first light across a 100 mile front.

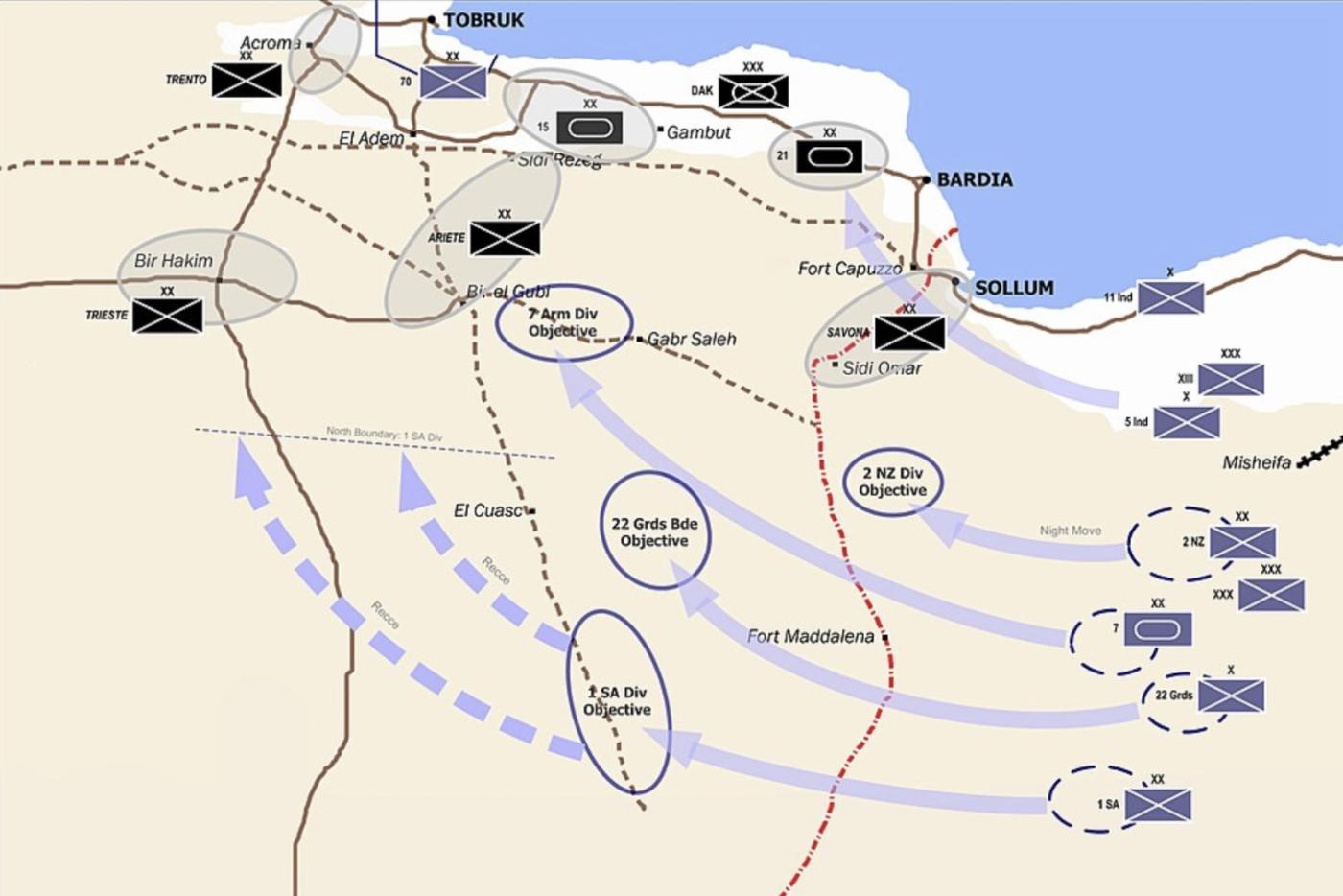

The plan was a classic Brooke and Auchinleck conception: an armoured wing sweep south and west far out in the open desert, then turn north to hit the German armour in its soft rear country, cut it from its supply, and simultaneously relieve Tobruk by pressure from outside as the garrison of Tobruk would make its own sortie. The striking power in tanks was considerable. In the main strike, 7th Armoured Division brought its armoured brigades of Crusader tanks and Stuarts, with some remaining Matildas in support; 1st South African Division and 4th Indian Division furnished the infantry weight on the inland flank; 13 Corps to the north with New Zealand Division and 1st Army Tank Brigade, built around infantry tanks Matilda II and the newer Valentine, would drive towards Tobruk’s wire and force the garrison and outside columns together. British artillery was plentiful and mobile, mostly 25-pounders well drilled in desert gunnery, with medium batteries backing them. Air cover existed in the shape of the Desert Air Force, which by this date had reorganised enough to put Hurricanes and Tomahawks constantly over the battlefield in cab-rank fashion. Crucially the RAF also had the bomber element to keep hammering Luftwaffe forward strips and Axis motor columns on the Via Balbia. It was not full air superiority, but it was far from the helplessness of early 1941. The RAF was now a decisive battlefield arm.

The surprise for Rommel came from two things at once: the sheer early date of the attack, and the direction of the main armoured thrust. His focus was on his siege of Tobruk and his own planned offensive eastward. His armour was deployed pointed towards the coast and the Tobruk line, not deep in the desert to guard his southern flank. When the British armour came sweeping through the emptier desert, literally by the end of the first day, on the evening of 18 November, they were already well inside his operational rear areas, on lines he had not thickly picketed. Signals intelligence later showed that on the morning of the 19th the German command net was full of urgent queries trying to find out where exactly the British main body even was.

Crusader was not a perfect tidy thrust. The armoured battles over the next days would dissolve into confused brigade-level swirls of dust, sudden clashes, and abrupt withdrawals, with 7th Armoured paying heavily to learn how to handle German 88 mm and 50 mm anti-tank guns properly. But the essential thing was achieved: Rommel’s timetable was smashed, his confidence shaken, and the siege of Tobruk broken by the end of the month when the New Zealanders linked up. Crusader forced Rommel to abandon his siege and retreat across Cyrenaica. The snapping open of this desert campaign on 18 November is significant because it marks the first true large scale modern combined arms offensive by the British in North Africa: armour moving fast in deep desert space, infantry divisions pressing on the coastal axis, artillery flexible and professionally handled, and air support synchronised enough to make the Luftwaffe feel hunted. Rommel was shocked because on that single dawn Britain had abruptly seized the initiative, and for the first time in the desert war it would not let go of it lightly.