Napalm

Napalm is one of those weapons whose name alone instantly conjures images of blazing jungles and the haunting human cost of the Vietnam War. Although it is now permanently tied to that conflict, the story of napalm actually begins decades earlier, in the early 1940s, inside a Harvard University laboratory. A team of chemists led by Louis Fieser had been tasked by the U.S. military with creating a more effective incendiary—something that would burn hotter, spread farther, and cling to its target instead of quickly evaporating like ordinary gasoline. Their solution was a thickened incendiary gel made by combining gasoline with a mixture of aluminum salts derived from naphthenic and palmitic acids. This unusual combination created a sticky, jelly-like substance that burned ferociously and adhered to anything it touched. They named it “napalm” by merging fragments of its two key components.

Although most people associate napalm with Vietnam, its first major use came in World War II. It was packed into canisters and dropped over Japanese cities, including Tokyo in 1945, where it helped fuel devastating firestorms. Military strategists quickly recognized how effective it was, and by the time the United States entered the Vietnam conflict, the formula had evolved into a cheaper, more potent version known as Napalm-B. This newer variant relied on a mixture of benzene, gasoline, and polystyrene. The polystyrene gave it the notorious glue-like consistency, the benzene helped it flow and spread, and the gasoline acted as the fuel. When ignited, it reached temperatures between 800 and 1,200 degrees Celsius and could continue burning for minutes, sticking to metal, buildings, and human skin alike.

The decision to use napalm in Vietnam was not accidental or incidental; it was formally approved at the uppermost levels of the U.S. government. Under President John F. Kennedy in 1962, the first large shipments were sent to support the South Vietnamese regime. As the war escalated under President Lyndon B. Johnson, its deployment widened dramatically. Senior defense officials, including Robert McNamara, authorized extensive use by the Air Force, Navy, and Marine Corps. The rules of engagement permitted the targeting of enemy positions, supply networks, and suspected Viet Cong hideouts, though in practice the areas struck often included towns, hamlets, and farmland filled with civilians.

Napalm became a standard tool in the U.S. arsenal throughout the war. Fighter-bombers such as the F-4 Phantom and A-1 Skyraider frequently carried 500- and 750-pound napalm canisters for close air support missions. It was used to clear jungle cover, opening up lines of sight and burning away hiding spots that traditional bombs or small-arms fire couldn’t reach. Aircrews also used it to prepare helicopter landing zones by scorching potential ambush sites before troop insertion. Its psychological effect was so powerful that some commanders openly acknowledged the fear it produced as part of its intended impact. A napalm drop created a rolling, roaring fireball that could demoralize even well-entrenched troops.

Estimating how much napalm was actually produced and dropped in Vietnam is challenging because records varied between branches and suppliers, but historians agree that millions of gallons were manufactured during the conflict. Hundreds of thousands of individual canisters were likely deployed between 1963 and 1973. Dow Chemical is often remembered as the principal manufacturer, but it was not alone—Hercules Inc. and Monsanto also produced substantial quantities. Workers at Dow later recalled that public protests over the company’s involvement were unlike anything they had experienced before, signaling a major shift in how society viewed corporate responsibility during wartime.

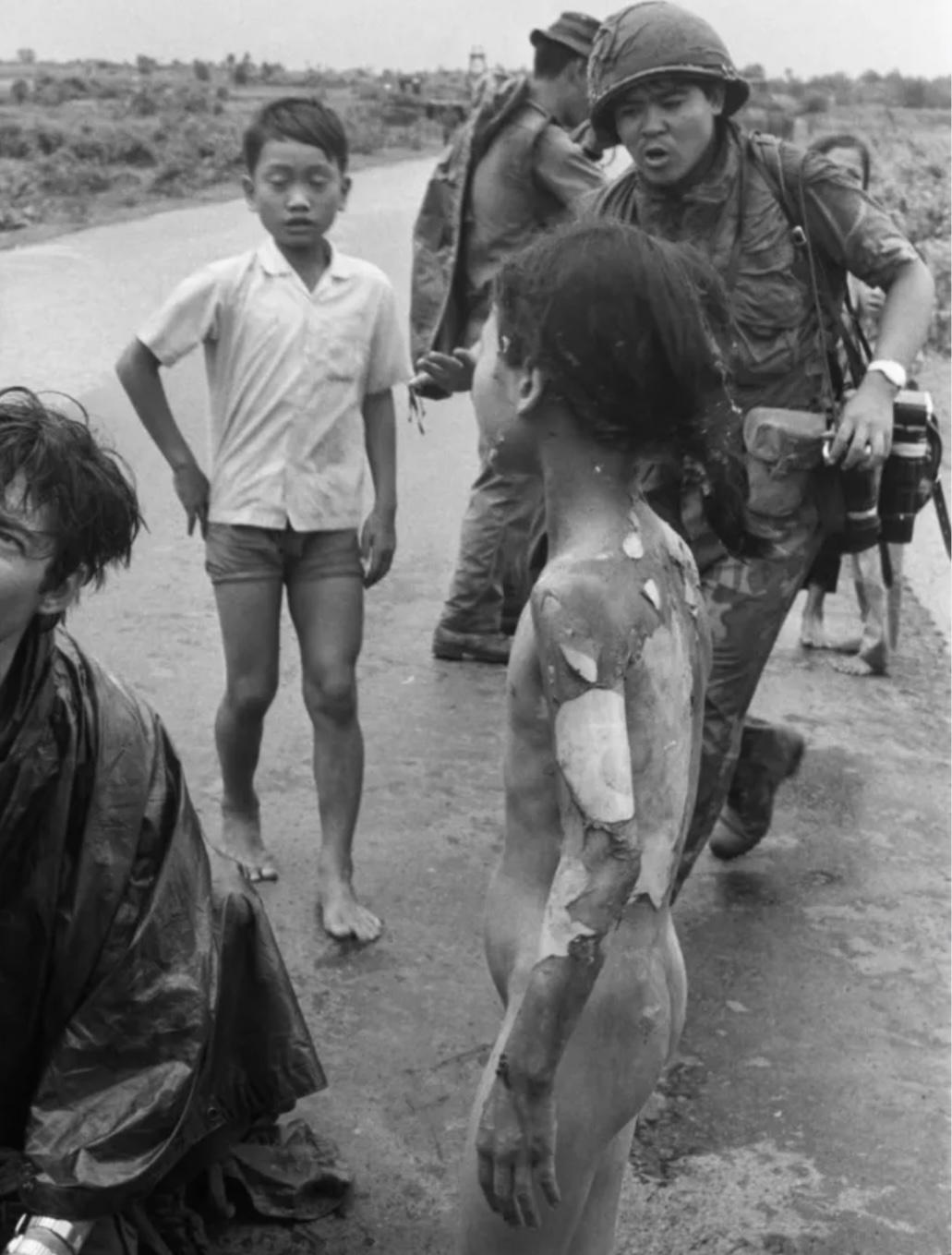

The effects of napalm on the ground were horrific. On people, it caused deep burns that could char flesh to the bone, often killing through shock, suffocation, or fumes. Those who survived typically faced lifelong pain, disfigurement, and medical complications. Perhaps no single image captured its impact more than the 1972 photograph of young Phan Thi Kim Phúc, running naked and screaming after being burned. That photo traveled the world, reshaping attitudes toward the war and fueling anti-war movements.

On the landscape, napalm left behind blackened zones of ash, destroyed crops, and areas of dead jungle that took years to recover. It could burn even on water, making it effective in marshes and rivers common in Vietnam’s geography. Strategically, it achieved short-term results—destroying bunkers, clearing vegetation, and breaking up enemy formations—but it also alienated large numbers of civilians, pushing many toward supporting the very forces the United States was attempting to defeat.

A few lesser-known facts add depth to its story. Pilots often had mixed reactions to deploying it, describing the fireball as visually stunning yet sickening once they saw the aftermath. Kim Phúc eventually survived, emigrated, and became a humanitarian advocating for children in war-torn regions. The U.S. military officially removed napalm from its inventory in 2001, replacing it with newer incendiary weapons that, although still destructive, avoided the infamous name that had become synonymous with the brutal face of modern warfare.