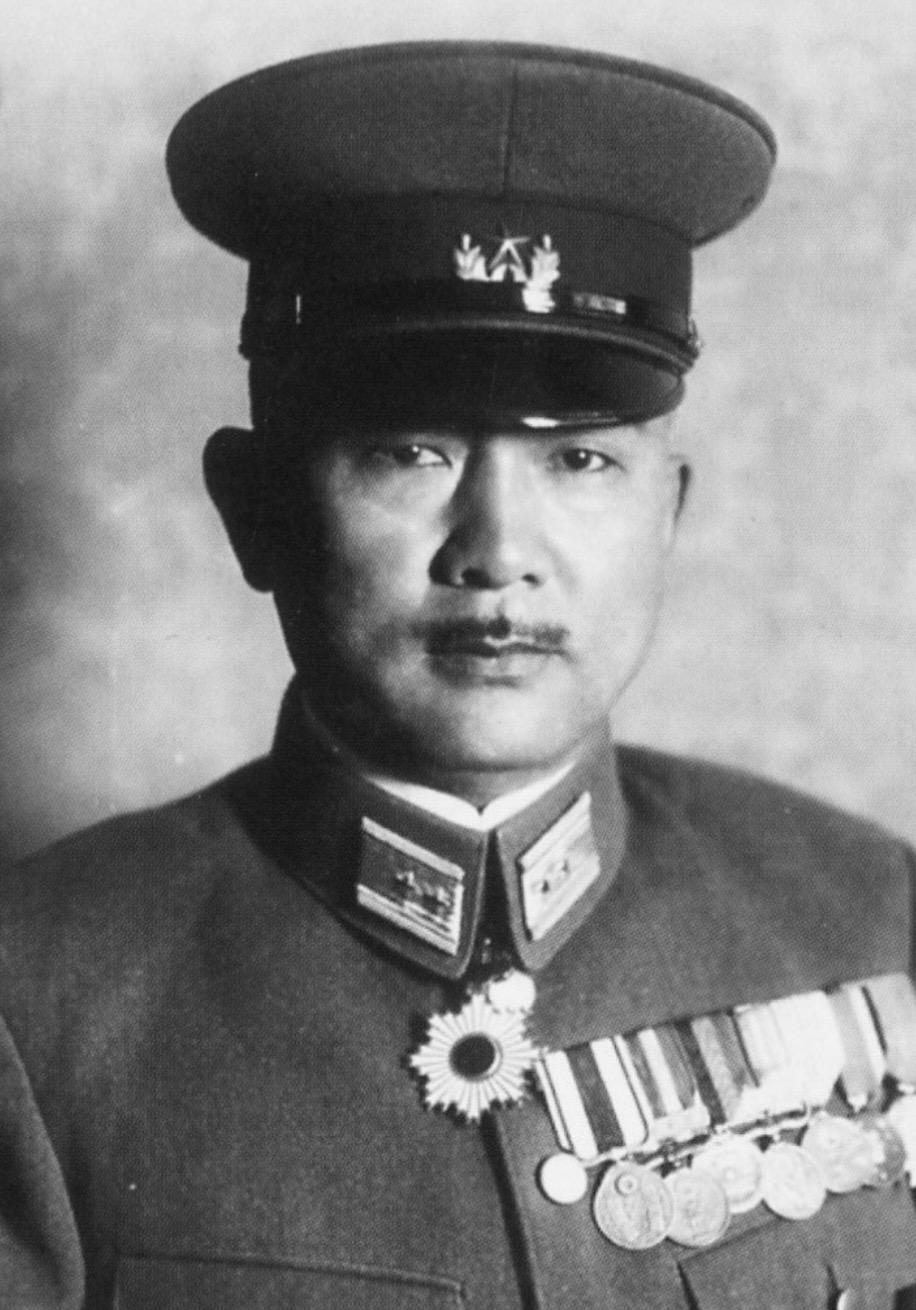

Lt General Tadamichi Kuirbayashi

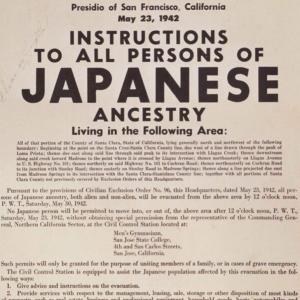

Tadamichi Kuribayashi was born on July 7, 1891, in Nagano Prefecture, Japan, into a family of former samurai background. From childhood he was raised in an environment that valued discipline, education, and loyalty to the emperor. Japan at the time was rapidly modernising, and a military career offered both prestige and opportunity. Kuribayashi proved to be an able student and entered the Imperial Japanese Army Academy, graduating in 1914 as a cavalry officer. He began his service during a period when Japan was expanding its military influence and modernising its armed forces along European lines.

In his early career he developed a reputation for seriousness, intelligence, and reliability rather than flamboyance. He attended the Army War College, graduating with distinction and marking himself as an officer suited for higher command and staff responsibilities. His rise through the ranks was steady. He served in various cavalry units and staff positions and was known for careful planning and organisational skill. During the 1920s he was selected for overseas duty, an opportunity given only to promising officers. From 1928 to 1930 he served as a military attaché in the United States and Canada. This period had a profound influence on his thinking. He travelled extensively, studied English, and observed American industry and society. He came to admire the immense industrial capacity of the United States and concluded that Japan would struggle to win any prolonged conflict against such a powerful nation. Despite these personal conclusions, he remained loyal to his country and continued his military career with dedication.

Returning to Japan, Kuribayashi continued to advance. He held positions within the Imperial Guard, one of the most prestigious formations in the Japanese Army, entrusted with protecting the emperor and the imperial palace. Service in this unit reflected both competence and trustworthiness. Throughout the 1930s he held command and staff roles as Japan expanded its operations in China and across Asia. He gained experience in logistics, administration, and operational planning. His approach to leadership emphasised discipline, preparation, and efficiency rather than reckless aggression. By 1940 he had been promoted to major general and later commanded the 2nd Imperial Guard Division. His ability to organise and lead large formations brought further recognition, and by 1943 he had reached the rank of lieutenant general.

Among his notable accomplishments before the end of the war was his role in modernising aspects of Japan’s cavalry and adapting traditional units to the realities of mechanised warfare. He also proved effective in staff positions, improving planning and coordination within the units he oversaw. His understanding of industrial warfare and logistics set him apart from many contemporaries. These qualities led to his selection for one of the most difficult assignments in the Pacific War. In June 1944 he was appointed commander of Japanese forces on Iwo Jima, a small but strategically important island located between the Mariana Islands and the Japanese mainland. The island served as an early warning station and fighter base against American bombing raids, and Japanese high command expected it to be targeted by U.S. forces.

When Kuribayashi arrived on Iwo Jima he quickly realised that defending the island using traditional Japanese tactics would result in swift defeat. Drawing on his knowledge of modern warfare and his understanding of American firepower, he devised a new defensive strategy. He ordered the construction of a vast network of tunnels, bunkers, and fortified positions across the island. More than eleven miles of tunnels were dug through volcanic rock, connecting command posts, ammunition depots, and defensive strongpoints. Mount Suribachi and other key areas were heavily fortified with concealed artillery and observation posts. He instructed his troops to avoid wasteful banzai charges and instead focus on disciplined, coordinated resistance designed to inflict maximum casualties and delay the enemy as long as possible.

When American forces landed on February 19, 1945, they encountered one of the most formidable defensive systems of the war. Kuribayashi ordered his troops to hold their fire until the landing beaches were crowded, then unleash concentrated artillery and machine-gun fire. The resulting battle lasted more than a month and became one of the bloodiest in the Pacific. American forces eventually captured the island after intense fighting, suffering heavy casualties. Kuribayashi directed the defence from underground headquarters as long as possible, but by late March Japanese resistance had been largely crushed. He is believed to have died during the final stages of the battle in March 1945, either leading a final attack or taking his own life when defeat became unavoidable. His body was never definitively identified.

Because he died before Japan’s surrender in August 1945, Kuribayashi did not live to see the end of the war or the postwar transformation of Japan. After the war, however, his reputation gradually emerged from both Japanese and American accounts. American commanders and historians recognised the effectiveness of his defensive strategy and the discipline he imposed on his troops. His leadership at Iwo Jima was studied in military academies as an example of innovative defensive warfare against overwhelming odds.

In Japan, Kuribayashi came to be regarded as one of the most capable and realistic commanders of the conflict. Personal letters he wrote to his family during the war were later discovered and published. These letters revealed a thoughtful and humane individual who cared deeply for his family and soldiers and understood the likely outcome of the war. His writings expressed concern for Japan’s future and sorrow over the suffering caused by the conflict. They helped shape a more nuanced view of him as not merely a determined military leader but also a reflective and compassionate man caught in the tragedy of war.