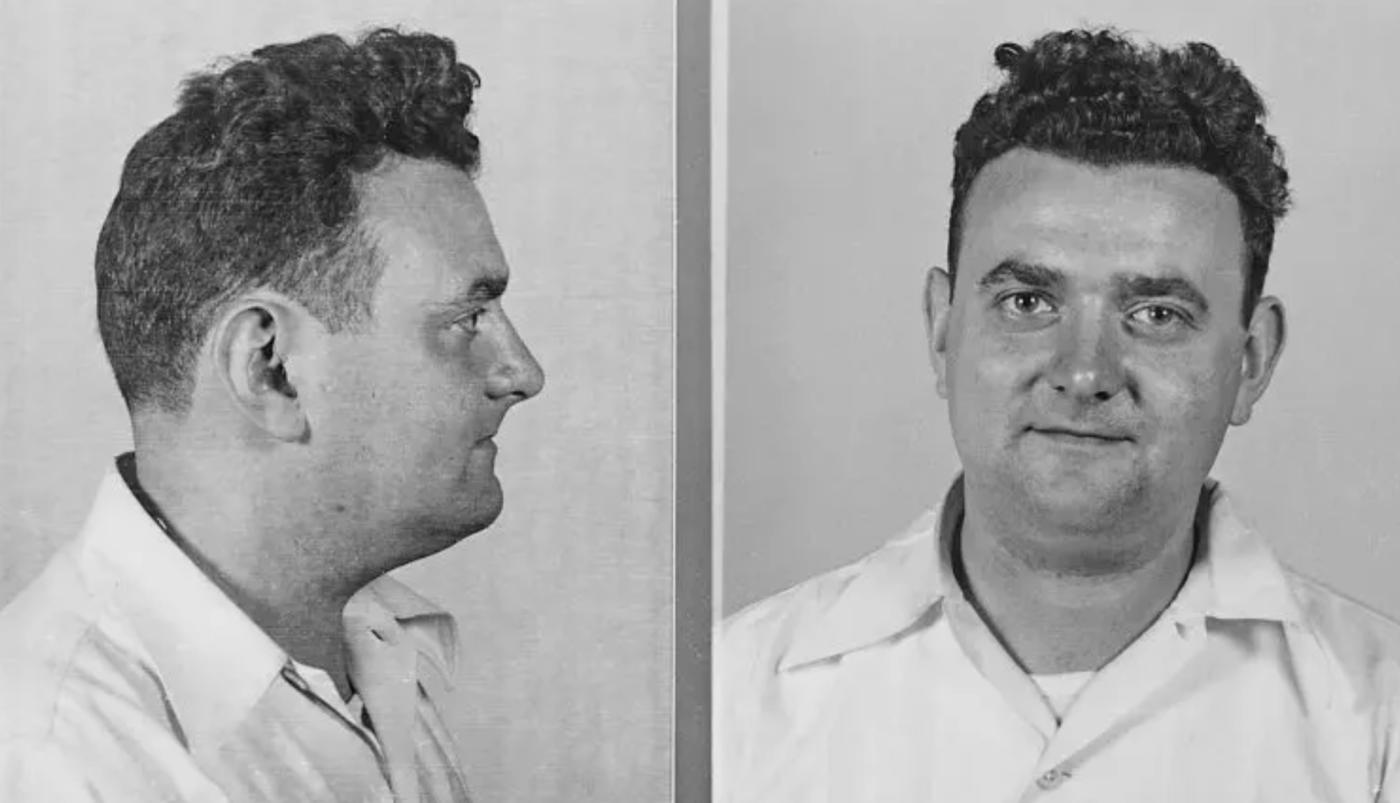

Harry Gold Spy

Harry Gold’s involvement in one of the most damaging espionage operations of the twentieth century stemmed from a mixture of personal insecurity, misplaced gratitude and a naïve belief that helping the Soviet Union would prevent nuclear domination by any single nation. Born Henrich Golodnitsky in 1910 to struggling Russian Jewish immigrants, he grew up in Philadelphia in a family that endured poverty, discrimination and constant instability. Gold was quiet, diligent and painfully eager to please. Throughout his life he carried a strong sense of indebtedness to anyone who showed him kindness, a trait that would be carefully and deliberately exploited by Soviet intelligence.

His route into espionage began during the hardships of the Great Depression. After losing a job, he was helped by a coworker with left-leaning political ties. Grateful and eager to belong, he drifted into circles sympathetic to the Soviet Union and eventually came to the attention of Jacob Golos, a senior figure for Soviet intelligence in America. Golos appealed to Gold’s desire to feel valued and useful. Gold never joined the Communist Party and was not motivated by ideology; he became a courier because he wanted to repay favors and because he convinced himself that sending technical information to the USSR was helping a friendly nation fight fascism.

The secret information he ultimately passed on was of extraordinary significance. During the Manhattan Project the Soviets were desperate for detailed, verified insights into the design, assembly and theoretical basis of the atomic bomb. Klaus Fuchs, the brilliant physicist working in the British delegation at Los Alamos, had access to virtually the entire scientific core of the project. To move the information to Soviet handlers, an American contact was needed—someone inconspicuous, obedient and unlikely to draw attention. Gold perfectly fit the role.

Gold met Fuchs in Santa Fe in June 1945. Fuchs handed him packets containing sketches of the implosion device, mathematical formulas explaining the timing mechanism, analyses of plutonium compression, and written summaries of experimental results conducted at Los Alamos. The documents were often extremely compact, sometimes folded into tiny envelopes or written in minuscule handwriting, and Gold carried them in the most mundane way possible—tucked inside a cheap paper shopping bag or concealed in his coat pockets. Gold typically received these items during short, discreet street encounters and then delivered them to Soviet contacts in New York. He handled the material with care but never fully appreciated its gravity. Decades later declassified Soviet archives confirmed that the data Fuchs passed—transported through Gold—allowed Soviet scientists to validate their theoretical models and drastically shorten the development time of their first atomic bomb.

Gold also moved industrial and scientific intelligence unrelated to the bomb, including details of chemical processes and factory output, much of which he collected from acquaintances or workplaces. But nothing compared to the atomic material, which he treated with the same almost clerical sense of duty he applied to every task in his life. He later remarked that he assumed the Soviets already possessed the essentials and that he was simply reinforcing information they likely knew. This was a profound self-deception, and it spared him from confronting what he was really doing.

The unraveling began when Fuchs was arrested in Britain and confessed in January 1950. He described his American courier in detail, enabling the FBI to track Gold down. Gold was arrested in Philadelphia on May 23, 1950. Realizing the evidence against him was overwhelming, he immediately cooperated. His guilty plea was entered before Judge James P. McGranery in federal court in Philadelphia on June 22, 1950. His sentencing took place on December 21, 1950, when he received thirty years in federal prison, the maximum sentence possible under the charges.

Gold’s cooperation became a major turning point in the early Cold War spy investigations. His careful, exhaustive testimony laid bare numerous clandestine networks and directly contributed to the uncovering of David Greenglass, whose statements led to the prosecution of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg. Although Gold never meant to destroy the lives of others, his complete confession made him a critical figure in the most famous espionage case in American history.

He served his sentence at Lewisburg Federal Penitentiary, working quietly in the prison hospital laboratory. Guards and inmates described him as polite, remorseful and wholly non-confrontational. After fifteen years, the parole board concluded that he presented no threat. He was released on parole in May 1965 and formally completed his sentence in 1966.

Gold returned to a modest, anonymous existence in Philadelphia, working once again as a medical laboratory technician. He avoided publicity and rarely spoke about his past. Those who interacted with him in his later years often never knew he had carried some of the most important scientific secrets of the century in a humble paper bag. He remained filled with regret, insisting that he had never intended to alter the course of world politics and had believed he was helping a wartime ally rather than enabling a nuclear arms race. He lived quietly until his death in 1972 at age sixty-two.