Fire Guards

During the Second World War, one of the least celebrated but most essential elements of Britain’s civil defence was the unpaid fire guard. These volunteers stood watch over rooftops, factory yards, and residential streets during and after air raids, looking specifically for the incendiary devices that German bombers dropped in vast numbers. Their role emerged not from military doctrine but from urgent necessity. When the Blitz began in 1940, the authorities quickly realised that while high-explosive bombs caused major destruction, the small magnesium and thermite firebombs were responsible for a far greater proportion of large, spreading fires. Fire brigades could not be everywhere at once, especially when whole districts were alight, so a decentralised system of immediate local response was required.

The initial concept came from the British government’s Air Raid Precautions (ARP) planners during the late 1930s. They predicted that incendiaries would be among the greatest threats to cities and believed that every street, building, and workplace needed its own first line of defence. The Ministry of Home Security was responsible for shaping this into a nationwide scheme. At first the volunteers were called fire watchers, and later, under the Fire Prevention (Business Premises) Order of 1941, they were officially termed fire guards. What began as a small, rather informal arrangement became compulsory service for many people by 1941, especially those working in factories, offices, and warehouses in target areas.

Training for fire guards was practical rather than extensive. Volunteers were taught how to deal with different types of incendiary bombs, how to use stirrup pumps, sand, and water jets, and how to work safely on rooftops during blackouts. A typical session included practising extinguishing burning thermite in controlled conditions and learning to recognise when a firebomb might explode after an initial burn. Many fire guards were ordinary civilians with no technical background, yet by repetition and necessity they learned how to neutralise a device before it ignited a full-scale fire. Larger buildings often had organised squads with a simple chain of command, fire points stocked with equipment, and patrol routes.

Their presence made a measurable difference. Incendiary bombs were designed to ignite quickly and spread through roofs and attics, places difficult for fire brigades to reach in the chaos of a raid. Fire guards, however, were already in position and equipped to act within seconds. In countless cases, a single volunteer with a bucket of sand or a stirrup pump stopped a blaze that might otherwise have consumed a whole block. Industrial sites, which were prime targets, particularly benefited from this rapid response. Some factories credited their continued operation to their fire guard units, which kept small outbreaks under control until professional crews could attend.

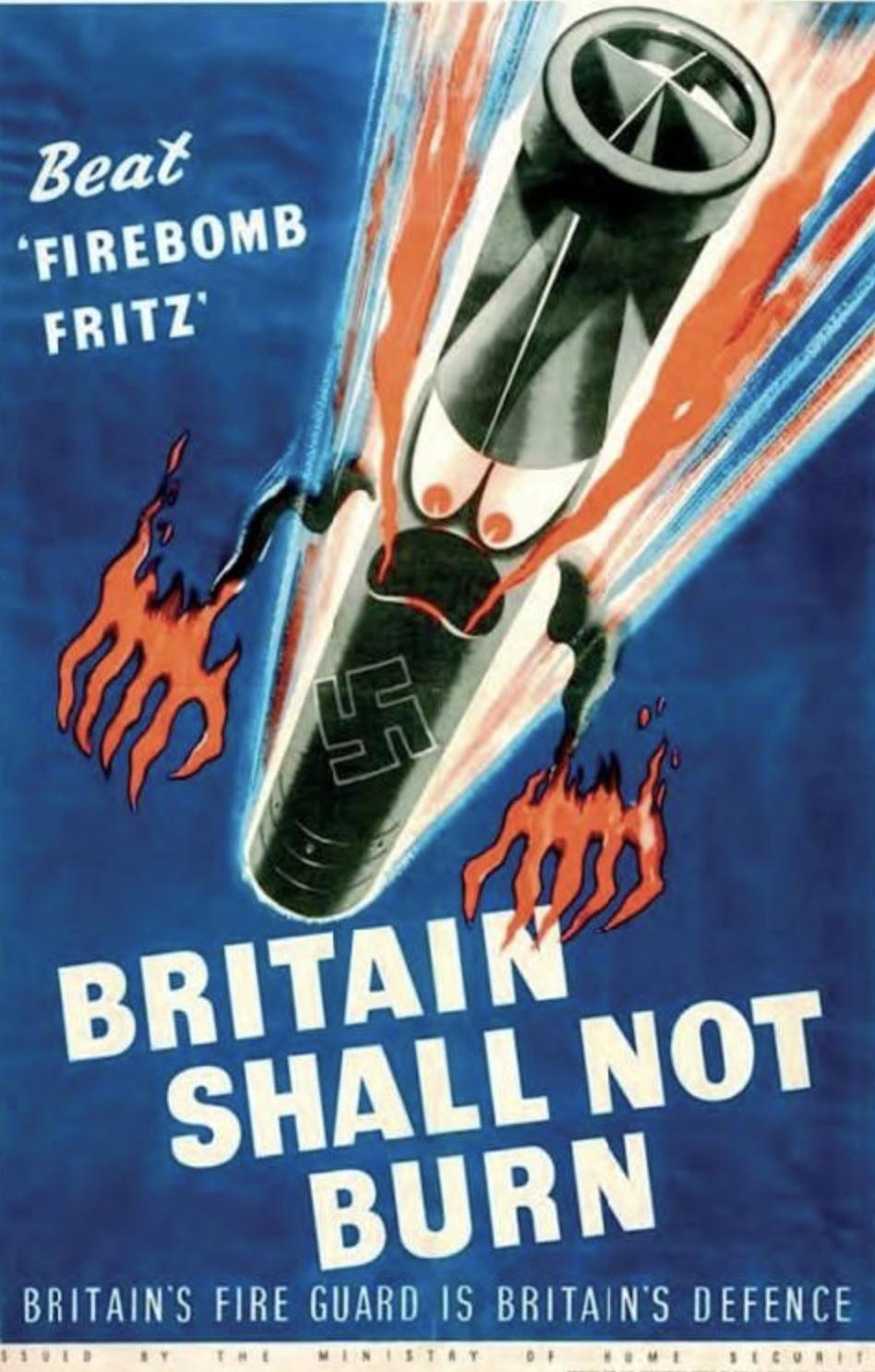

Beyond the practical work, there was a strong public morale component. Posters, pamphlets, and radio announcements promoted the importance of fire guarding as a patriotic duty. One well-known poster showed an incendiary bomb with the caption this is the enemy, reminding citizens of the need for vigilance. Another urged don’t let a spark become a fire, emphasising that any unattended bomb could destroy whole neighbourhoods. Recruitment materials often portrayed fire guards as ordinary people doing extraordinary work, reinforcing the idea that protecting Britain’s cities was a shared civilian responsibility.

Interesting, too, is how social dynamics shaped the service. Fire guarding brought together people who might never otherwise have met: office clerks, factory labourers, retired men, young women, and even teenagers in auxiliary roles. Night watches became times for conversation, community, and mutual support during the darkest hours of the war. In heavily bombed areas such as London, Coventry, and Hull, fire guard posts sometimes functioned as small social hubs, providing a sense of solidarity in a period of relentless threat.

While the fire guards were not part of the armed forces, their contribution was indispensable. They operated in danger, often without recognition, and their quick actions prevented untold destruction. By the end of the war, Britain’s official reports acknowledged that the fire guard system had saved thousands of buildings and helped keep vital wartime production running. Their story remains a compelling example of civilian courage and organisation in the face of extraordinary circumstances, a reminder that the defence of a nation can depend as much on ordinary citizens with simple tools as on soldiers and weapons.