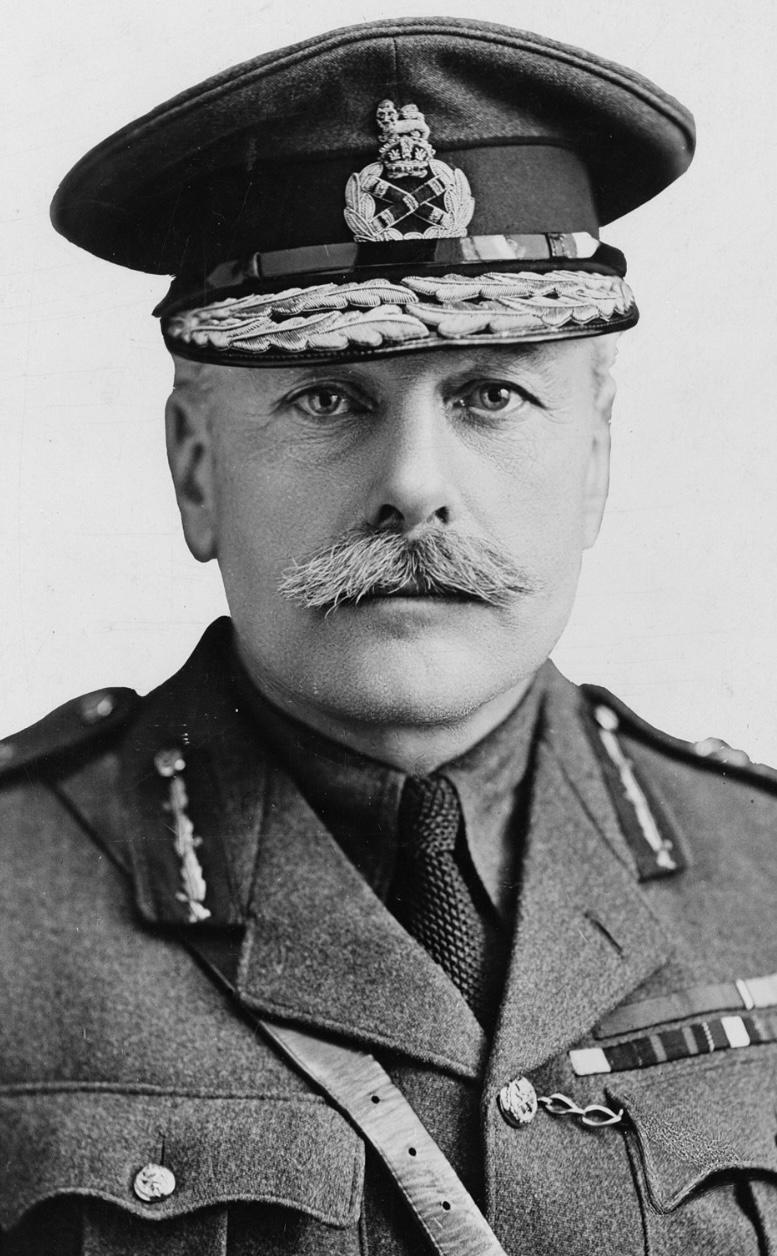

Field marshal Douglas Haig

Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig died on 29 January 1928, closing the life of one of the most consequential and controversial British commanders of the First World War. By the time of his death he was a national figure, honoured with the highest military rank and titles, yet also shadowed by a reputation that had grown steadily harsher in the years after 1918. He had become, in popular memory and later debate, “Butcher Haig”, a nickname rooted in the appalling losses of the Western Front and especially the Somme, where his approach to command and tactics has been argued over for more than a century.

Haig was born in Edinburgh on 19 June 1861 into a wealthy family with strong social and business connections. He was educated at Clifton College and then at Brasenose College, Oxford, before training at the Royal Military College, Sandhurst. He joined the 7th (Queen’s Own) Hussars and came of age in a British Army that still thought in terms of cavalry shock action, imperial policing, and short wars. Early service in India and Sudan helped shape his habits of discipline and staff work, and he built a reputation as a diligent officer with an instinct for organisation and a cool temperament under pressure.

A defining early influence on his career was his involvement in the South African War (1899–1902), where he served in staff roles and saw, at first hand, how modern rifles, artillery, and entrenchments could blunt traditional attacks. After the war he rose through important staff appointments, including work at the War Office and with the British Expeditionary Force in its pre-war planning. When the First World War broke out in August 1914, Haig was already a senior commander. He led I Corps in the opening campaigns, then commanded First Army, and by December 1915 he replaced Sir John French as Commander-in-Chief of the British Expeditionary Force, putting him in overall charge of Britain’s main effort on the Western Front.

It was in this role that Haig became inseparable from the great battles of attrition: the Somme in 1916, Passchendaele (Third Ypres) in 1917, and the response to Germany’s major offensives and eventual defeat in 1918. Haig’s supporters have long argued that his central problem was strategic reality: Germany could not be beaten quickly, and Britain’s army, rapidly expanded from a small professional force into a mass citizen army, had to learn grim lessons against an enemy dug into deep defences. His critics have argued just as forcefully that he too often treated enormous casualties as the unavoidable price of progress, clung for too long to optimistic assessments, and relied on plans that underestimated the strength of modern defensive firepower.

The Somme remains the fulcrum of his reputation. The offensive began on 1 July 1916 as a joint British-French effort intended to relieve pressure on the French at Verdun and to break German lines in Picardy. The first day alone became the darkest in British military history: tens of thousands of British soldiers were killed, wounded, or missing in a single day. Haig did not create the Somme plan on his own, but as commander-in-chief he approved the broad approach and persisted with the offensive for months. Supporters argue that the Somme forced Germany to commit reserves, wore down experienced German formations, and accelerated the shift toward a more modern British army, improving artillery coordination, tactics, and the use of creeping barrages and bite-and-hold methods. Critics respond that early assumptions about the effect of the preliminary bombardment were wrong, that infantry were sent forward too rigidly against intact machine-gun positions, and that senior command underestimated how difficult it would be to exploit any breakthrough across shattered ground under fire. The core of the “Butcher Haig” image comes from this collision between high command plans and the human cost borne by battalions on the ground.

The nickname itself gained power in later decades, but the disquiet about casualties was not only a later invention. Even during the war there were arguments within government and the press about strategy, manpower, and the balance between Western Front offensives and other theatres. Haig was criticised for the scale of losses at the Somme and again at Passchendaele, where the battlefield became synonymous with mud, shell holes, drowning, and stalled advances. His defenders have often countered that the Allies were fighting an industrial war in which no side found a painless solution, that the technology and tactics of 1916–17 were in a difficult transitional phase, and that by 1918 the British Army had become markedly more effective, using improved artillery methods, tanks, aircraft reconnaissance, and more flexible infantry tactics. Even so, the central moral and historical question remains: whether Haig made the best of grim necessities or whether he prolonged suffering through avoidable decisions.

Haig’s own personality and style fed the controversy. He was known for a reserved manner, a strong belief in duty, and an unshakable confidence in ultimate victory. He was also a cavalryman by background and continued to speak of breaking through and exploiting with mounted forces, even as the war’s reality repeatedly showed how hard it was to convert limited tactical gains into a decisive operational rupture. He relied heavily on staff work and on reports that sometimes painted a hopeful picture, and he could be slow to accept bad news when it conflicted with plans already set in motion. Yet he was not simply static: the British Army’s gunnery, counter-battery techniques, logistics, medical evacuation systems, and combined-arms coordination all advanced substantially under his command. Whether these improvements came because of Haig, in spite of him, or as an inevitable evolution of wartime learning is part of why his legacy remains so disputed.

After the Armistice in November 1918, Haig remained a famous public figure. He was granted titles and honours, and he became deeply involved in the welfare of ex-servicemen. One of the most lasting and significant parts of his post-war life was his role in veteran support and remembrance. He served as a leading figure in the British Legion (founded in 1921), and he was closely associated with the “poppy appeal”, which became an enduring symbol of remembrance and fundraising for veterans and their families. Whatever people think of his wartime decisions, his post-war work helped shape how Britain cared for those who had served and how the nation publicly remembered the fallen.

By the late 1920s Haig’s health declined. When he died on 29 January 1928, the event was treated as the passing of a major national leader of the war years. There was a large public response, with ceremonies and crowds reflecting both respect for his rank and the scale of the war he represented. The funeral became a significant occasion of state and military mourning, with the rituals of empire and the sombre memory of the trenches meeting in public view.

Haig was buried at Dryburgh Abbey in the Scottish Borders, a historic abbey beside the River Tweed. The choice of Dryburgh connected him to Scotland and to a landscape associated with national history and reflection. His grave there became a place of memory, visited by those interested in the First World War, British military history, and the continuing debate about how to judge commanders whose decisions were made in conditions of extreme uncertainty and relentless pressure.

In the decades after his death, Haig’s public image moved in waves. For a time, especially in the immediate post-war period, he was celebrated as the soldier who had helped deliver victory in 1918. Later, as the war came to be seen more and more as a tragedy of mismanagement and mass slaughter, the harshest interpretations hardened, and “Butcher Haig” became a shorthand condemnation. More recent historical work has often tried to weigh competing realities: the murderous effectiveness of entrenched defence, the political demands placed upon Allied commanders, the growing sophistication of the British Army over the course of the war, and the question of what alternatives were realistically available. That argument is unlikely to end, because it is not only about Haig as a man, but about how societies judge leadership amid catastrophe.