On this day in military history…

On 1 February 1917, Germany announced that it would resume unrestricted submarine warfare, a decision that marked a dramatic escalation in the First World War and reflected how desperate the situation had become for the German leadership. By this point, the war had dragged on for more than two and a half years, far longer than any of the major powers had expected in 1914. Germany was increasingly strained by the British naval blockade, which limited food and raw materials entering the country and caused serious hardship for civilians. Many German military leaders believed that only a bold and ruthless strategy at sea could break the deadlock and force the war to end on Germany’s terms.

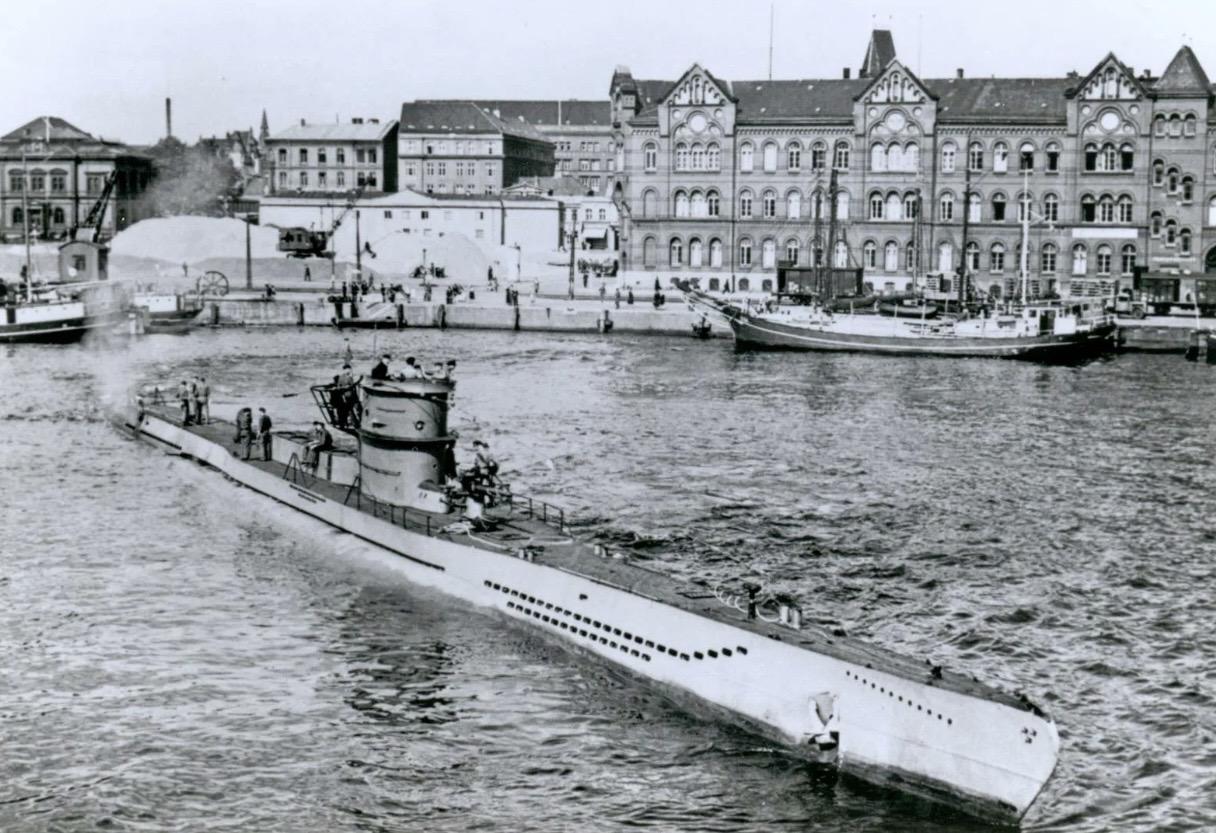

Unrestricted submarine warfare meant that German U-boats would attack any ship approaching Allied ports, regardless of whether it was a military vessel, a merchant ship, or even a neutral ship. Unlike traditional naval warfare, submarines could not easily follow established rules such as warning ships before attack or allowing crews to escape safely. Surfacing to give warnings made U-boats extremely vulnerable, so German commanders argued that effectiveness required surprise and total freedom of action. The goal was to sink merchant shipping faster than Britain and its allies could replace it, thereby starving Britain into submission within a matter of months.

This decision was widely seen, even at the time, as an act of desperation. Earlier in the war, Germany had already experimented with submarine attacks on merchant shipping, most famously in 1915 when the British passenger liner Lusitania was sunk, killing nearly 1,200 people, including American citizens. International outrage followed, particularly from the United States, which was still neutral at the time. As a result, Germany temporarily pulled back from unrestricted attacks and issued pledges, such as the Sussex Pledge in 1916, promising to limit submarine warfare and protect civilian lives. By early 1917, however, German leaders concluded that these restraints were no longer sustainable if they were to win the war.

Other nations strongly objected to the renewed policy. Neutral countries, especially the United States, warned Germany that attacking civilian and neutral shipping violated international law and basic humanitarian principles. President Woodrow Wilson had repeatedly told Germany to stop such practices, emphasizing that the loss of civilian life at sea was unacceptable. Germany was well aware that resuming unrestricted submarine warfare would almost certainly bring the United States into the conflict, but military leaders calculated that Britain would collapse before American troops could make a decisive difference.

There are several interesting and revealing aspects of this decision. German planners estimated that Britain would be forced to surrender within six months due to food shortages if shipping losses reached a certain level. Initially, U-boats were highly successful, sinking enormous amounts of Allied and neutral shipping in the spring of 1917. However, this success also pushed neutral opinion firmly against Germany. The United States broke off diplomatic relations with Germany shortly after the announcement, and in April 1917 formally entered the war on the Allied side. At the same time, the Allies began to adapt by introducing convoy systems, improved anti-submarine tactics, and new technologies, which gradually reduced the effectiveness of the U-boat campaign.

In hindsight, the decision of 1 February 1917 is often viewed as a turning point in the war. While it was intended to bring about a swift German victory, it instead helped unite world opinion against Germany and brought a powerful new enemy into the conflict. The policy highlighted how total and unforgiving the war had become, with civilian lives increasingly caught in the middle. What began as a calculated gamble born out of frustration and scarcity ultimately contributed to Germany’s defeat,