On this day in military history…

On 12 January 1943 the long, suffocating ring around Leningrad was finally split, not by a sudden collapse of German will but by a carefully prepared Soviet offensive that brought together experience, massed firepower, and a ruthless understanding of the ground. For nearly a year and a half the city had survived on starvation rations, improvised ice routes, and sheer endurance. What the Red Army set out to do that winter was not yet the complete lifting of the siege, but something just as vital: to punch a narrow land corridor through the German positions south of Lake Ladoga and restore a reliable supply route into the city.

The operation was known as Operation Iskra, and its objective was brutally simple. German forces held a narrow but heavily fortified strip of land between the town of Shlisselburg and the settlement of Mga, sealing Leningrad off from the rest of the Soviet Union. This bottleneck, only about sixteen kilometres wide, was defended by dug-in infantry, artillery positions frozen into the earth, and minefields laid in depth. Previous Soviet attempts to break through here had failed at enormous cost, but by January 1943 the balance of skill and preparation had shifted.

On the Soviet side, coordination was far better than in earlier efforts. The attack was planned jointly by the Leningrad Front and the Volkhov Front, with overall direction shaped by Georgy Zhukov, whose recent experience at Stalingrad had reinforced the importance of overwhelming force applied at a narrow point. On the western side of the corridor, troops under Leonid Govorov attacked eastward from the Leningrad perimeter. From the east, formations commanded by Kirill Meretskov advanced westward. The intention was not a sweeping breakthrough but a precise meeting of the two fronts, cutting the German line like a blade.

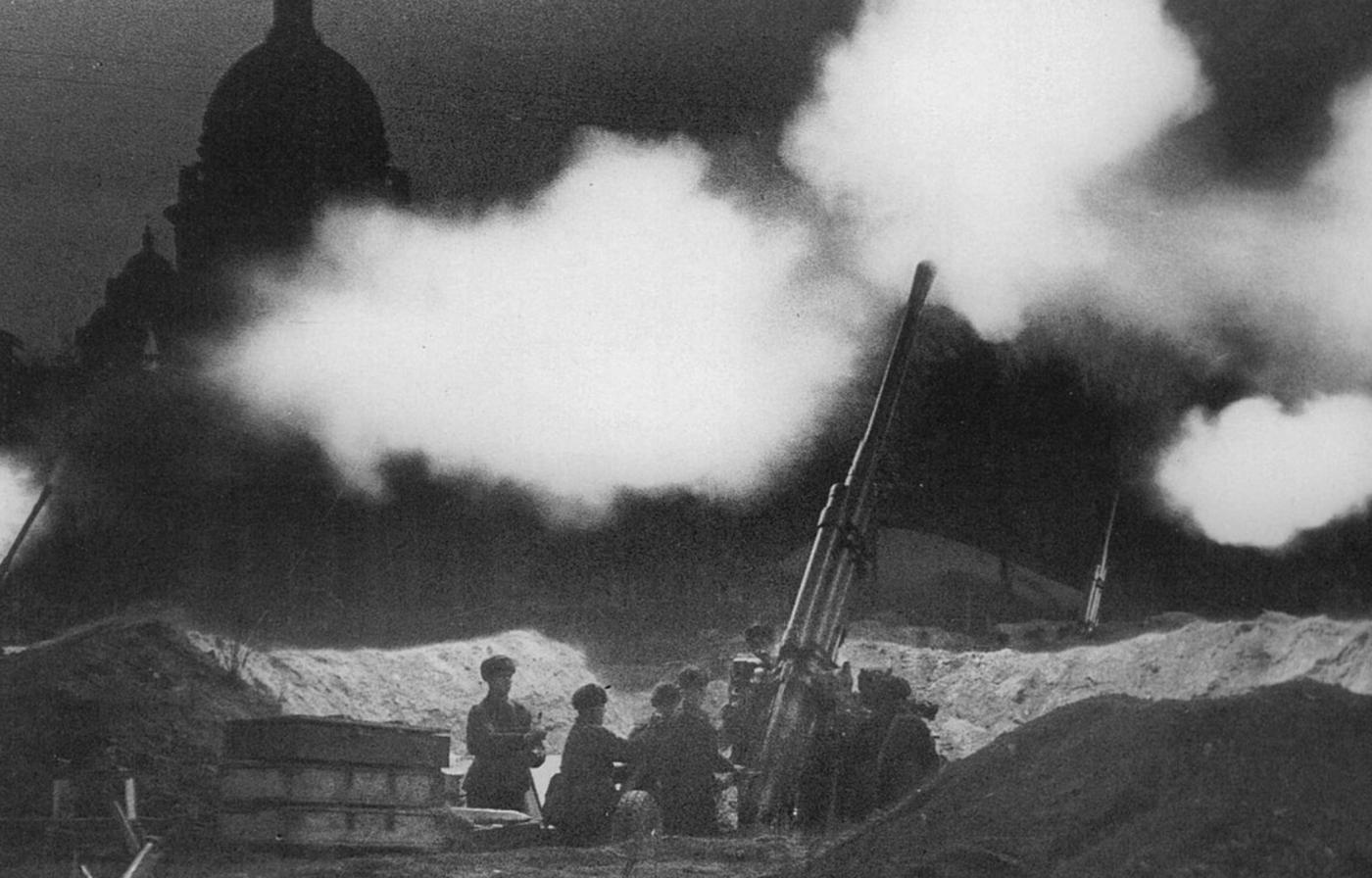

What made the assault different from earlier failures was the scale and concentration of firepower. Soviet artillery was massed in unprecedented density for this sector, with thousands of guns and mortars registered in advance on known German positions. Katyusha rocket launchers, whose shrieking salvos had both physical and psychological impact, saturated trenches and rear areas. When the barrage opened in the early hours of 12 January, it was not a brief preparation but a sustained, methodical destruction of wire, bunkers, and communication lines. German defenders later described entire trench systems simply vanishing under the bombardment.

Infantry assaults followed closely behind the fire, advancing over frozen ground under cover of smoke. Engineers played a crucial role, clearing paths through minefields while under fire and bridging anti-tank ditches so armour could follow. Soviet tanks, including T-34s adapted as best as possible for winter fighting, were committed in support of the infantry rather than in reckless charges. Though the terrain of forests, swamps, and frozen marshes limited their manoeuvre, their presence helped suppress German strongpoints that had survived the initial artillery storm.

Fighting was savage and close-range. Villages such as Lipka and workers’ settlements along the Neva changed hands multiple times, and progress was measured in hundreds of metres per day. German resistance was stubborn, but the defenders were short of reserves and increasingly isolated by Soviet fire that severed supply routes. Crucially, Soviet command resisted the temptation to widen the attack too early. Everything was focused on forcing the corridor open, no matter how narrow, and holding it.

On 18 January the two Soviet fronts finally linked up near Shlisselburg. The land corridor they created was only about eight to ten kilometres wide, well within range of German artillery, but it was enough. Almost immediately, work began on building a road and a railway line through the gap, often under shellfire. Within weeks, trains were running into Leningrad, bringing food, ammunition, fuel, and reinforcements in quantities that had been impossible during the worst months of the siege.

The effect on the city was dramatic. Rations increased, industrial output recovered, and the constant fear of total starvation began to recede. Militarily, the Germans now faced a Leningrad that could be supplied and reinforced, making the siege far more costly to maintain. Although the city was not fully liberated until a year later, the psychological and strategic balance had shifted decisively. The siege no longer felt like an inescapable death sentence but a problem that could be solved by force.

What made 12 January 1943 so significant was not just the breakthrough itself, but what it represented. The Red Army demonstrated that it had learned from earlier disasters: how to coordinate fronts, how to use artillery scientifically, how to match objectives to available strength. The narrow strip of frozen ground south of Lake Ladoga became a lifeline, and from that moment the slow crumbling of the German position around Leningrad was no longer a matter of hope, but of time.