On this day in military history…

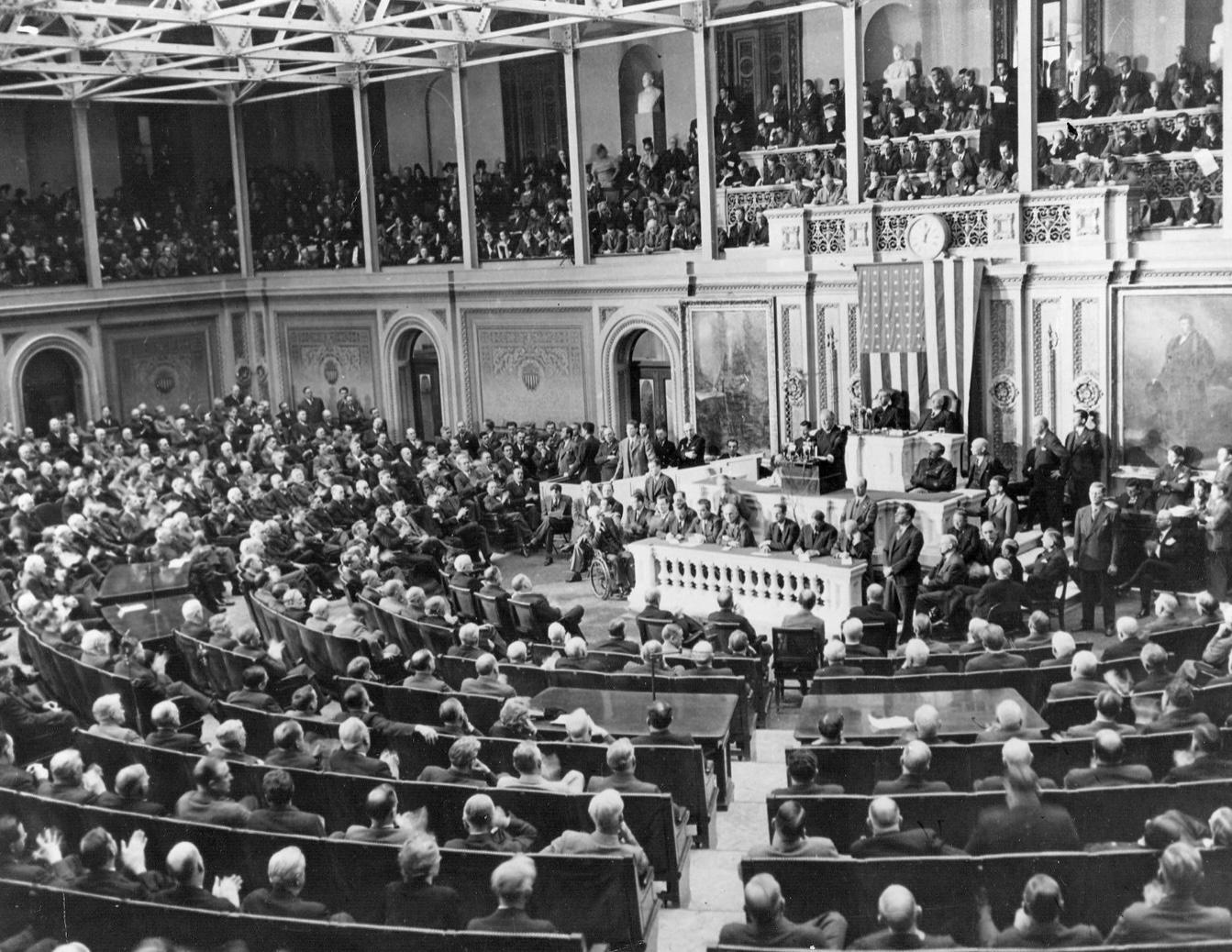

On 6 January 1941, Franklin D. Roosevelt addressed a joint session of the United States Congress in what became one of the most important speeches of his presidency. Often remembered for its articulation of the “Four Freedoms,” the address also laid out the moral, strategic, and economic case for providing large-scale aid to Britain through what soon became known as the Lend-Lease scheme. Although the United States was still officially neutral in the Second World War, Roosevelt used the speech to argue that American security was inseparable from the survival of nations resisting aggression, especially United Kingdom.

Roosevelt spoke at a moment of acute international danger. By early 1941, most of continental Europe had fallen under Nazi control, and Britain stood largely alone against Germany. The United States was deeply divided: many Americans supported helping Britain, but a powerful isolationist movement opposed any step that might drag the country into war. Roosevelt framed the crisis not as a distant European conflict but as a direct threat to the American way of life. He argued that modern warfare meant oceans no longer guaranteed safety and that a world dominated by aggressive dictatorships would eventually endanger the United States itself.

Central to this argument was the proposal that the United States should act as what Roosevelt soon famously called the “arsenal of democracy.” Instead of sending American troops, the nation would supply weapons, equipment, food, and industrial materials to Britain and other countries fighting the Axis powers. The idea behind Lend-Lease was deliberately pragmatic: if a neighbor’s house was on fire, Roosevelt said in a later radio address, you did not argue about payment for the hose, you helped put out the fire. In the congressional speech, he emphasized that aiding Britain was far cheaper and safer than waiting until the United States had to fight alone.

The speech went beyond strategy and economics by grounding the policy in universal values. Roosevelt described four essential freedoms that people everywhere ought to enjoy: freedom of speech, freedom of worship, freedom from want, and freedom from fear. By linking Lend-Lease to these freedoms, he transformed what might have seemed like a technical supply program into a moral crusade. Supporting Britain was presented not merely as helping an ally, but as defending a vision of global order based on rights, security, and human dignity.

The immediate reception of the speech reflected the tensions of the time. Many members of Congress, particularly internationalists and Democrats, welcomed Roosevelt’s clarity and urgency. Editorials in major newspapers praised the president for giving moral direction and for explaining why neutrality no longer meant safety. However, isolationist politicians and groups such as the America First Committee were alarmed. They argued that Lend-Lease would entangle the United States in war and accused Roosevelt of edging the country toward conflict without an explicit declaration.

Public opinion gradually shifted in Roosevelt’s favor. Polls in early 1941 showed growing support for aiding Britain, especially after the president’s repeated explanations of the policy in speeches and radio “fireside chats.” When the Lend-Lease bill was formally debated in Congress, the ideas first set out in the January address dominated the discussion. Despite fierce opposition, the legislation passed in March 1941, giving the president sweeping authority to supply Britain and other nations with war material.

In hindsight, the significance of the speech is difficult to overstate. It marked a decisive step away from American isolationism and redefined national interest in global terms. The Four Freedoms became enduring symbols of Allied war aims and later influenced the language of the United Nations and postwar human rights thinking. Lend-Lease itself proved crucial to Britain’s ability to continue fighting during its most vulnerable period, providing everything from aircraft and tanks to food and raw materials.

An interesting and often overlooked aspect of the speech is how carefully Roosevelt balanced reassurance with warning. He repeatedly insisted that he was not asking Congress to declare war, yet the logic of his argument made clear that neutrality in the old sense was no longer possible. Less than a year later, the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor brought the United States directly into the conflict, and Roosevelt’s January 1941 address came to be seen as the moment when the nation was intellectually and morally prepared for that step.

Ultimately, Roosevelt’s speech to Congress was not just a policy proposal but a turning point in American political culture. By presenting aid to Britain as both a practical necessity and a moral obligation, he reshaped how Americans understood their role in the world, setting the stage for the United States’ emergence as a global leader during and after the Second World War.