On this day in military history…

Operation Bodenplatte was the last major Luftwaffe offensive against Allied forces in the west and took place at dawn on 1 January 1945, during the final phase of the Battle of the Bulge. It was conceived as a single, large-scale surprise attack intended to cripple Allied tactical air power at a moment when German ground forces were still struggling to regain the initiative in the Ardennes. By late 1944 the Luftwaffe was no longer capable of sustained air combat, so Bodenplatte was designed as a one-day blow that would temporarily neutralise Allied air superiority and reduce the constant pressure of fighter-bomber attacks on German troops.

The objective was to strike Allied aircraft while they were parked and vulnerable on their airfields. In total, approximately 17 major Allied airfields in Belgium, the Netherlands, and northern France were targeted, with some sources counting up to 18 depending on how satellite and emergency strips are included. These airfields were used primarily by the RAF Second Tactical Air Force and the US Ninth Air Force, whose fighters and fighter-bombers had played a decisive role in disrupting German movements throughout the campaign. The Luftwaffe hoped that destroying aircraft on the ground would reduce close air support, reconnaissance, and interdiction long enough to allow German ground units either to stabilise the front or withdraw more effectively.

The operation was ordered by Hermann Göring and planned by Generalmajor Dietrich Peltz, commander of II. Jagdkorps. Adolf Galland, the General der Jagdflieger, strongly opposed the plan, arguing that the remaining experienced pilots were too valuable to be risked in a single operation with little chance of lasting success, but his objections were ignored. Planning was conducted in great secrecy, with strict radio silence imposed and many pilots given only limited information shortly before take-off.

Around 900 Luftwaffe aircraft were committed to Bodenplatte, of which roughly 850 were operational fighters. The force consisted almost entirely of single-engine aircraft, primarily Messerschmitt Bf 109s and Focke-Wulf Fw 190s, including both the radial-engined A-series and the newer Fw 190 D-9. More than thirty Jagdgeschwader took part, including JG 1, JG 2, JG 3, JG 4, JG 6, JG 11, JG 26, JG 27, JG 53, and JG 54, as well as units such as KG(J) 6, which despite its bomber designation operated fighters in this attack. Each wing was assigned specific airfields, with detailed routes planned to keep aircraft at very low altitude to avoid radar detection.

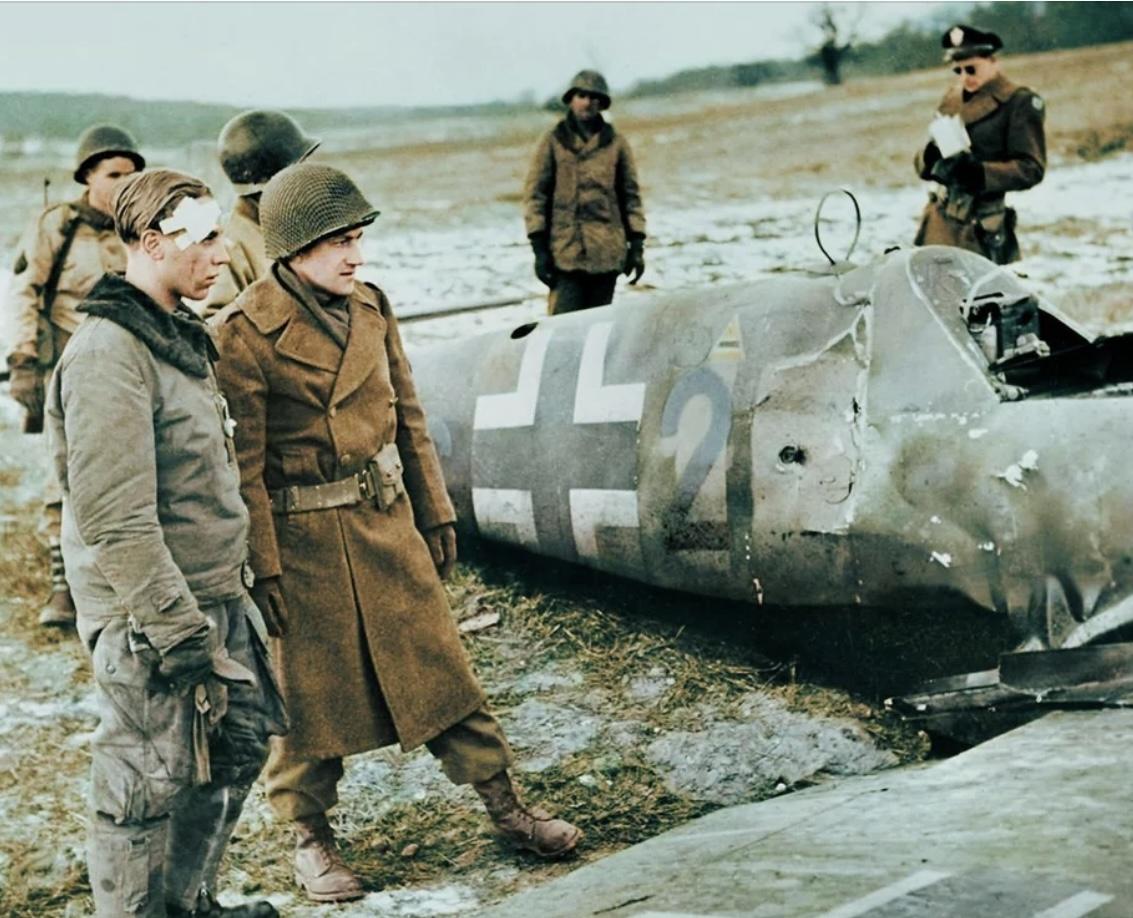

At first light, German fighters crossed the front lines at treetop height, navigating by rivers, roads, and railways. Surprise was achieved at several airfields, where strafing attacks destroyed aircraft lined up on dispersals and runways. However, the operation quickly descended into confusion. Poor weather, inadequate navigation training, and the inexperience of many pilots led to widespread errors. Some units attacked the wrong airfields, others failed to locate their targets at all, and returning aircraft were frequently engaged by German anti-aircraft batteries that had not been informed of the operation. Friendly fire accounted for a significant proportion of Luftwaffe losses.

In numerical terms, Bodenplatte inflicted substantial damage on the Allies. Approximately 300 Allied aircraft were destroyed on the ground and a similar number damaged, including Spitfires, Typhoons, Tempests, Mustangs, and Thunderbolts. Several airfields were temporarily put out of action. However, the impact was short-lived. Most Allied losses were of aircraft rather than pilots, and the Allies had vast reserves of both. Many damaged aircraft were repaired, replacements arrived quickly, and most airfields resumed operations within days or even hours.

The Luftwaffe’s losses were devastating by comparison. Around 280 German aircraft were destroyed or damaged, but the most critical losses were the pilots themselves. A very high proportion of those killed or captured were experienced leaders, including numerous Staffelkapitäne and Gruppenkommandeure. These men were irreplaceable at this stage of the war, and their loss shattered what remained of the Luftwaffe’s operational effectiveness in the west.

One of the most striking ironies of Bodenplatte is that it was launched on New Year’s Day in the belief that Allied forces would be relaxed or distracted, yet many Allied units were on alert, and some pilots managed to take off under fire and immediately engage the attackers. Adolf Galland later described the operation as the moment the Luftwaffe effectively “bled to death,” not because it failed to destroy enemy aircraft, but because it destroyed the last experienced core of its own fighter force. Within days, Allied air superiority was fully restored, and the Luftwaffe never again mounted an operation on such a scale in the western theatre.