On this day in military history…

On October 14, 1962, a routine American surveillance mission over the island of Cuba would trigger one of the most dangerous confrontations of the Cold War. On that day, a U-2 reconnaissance aircraft flew high above Cuban territory, its powerful cameras snapping images of the ground below. At first glance, the photos seemed unremarkable, but upon analysis, they revealed something that sent shockwaves through the United States government: the unmistakable signs of Soviet medium-range ballistic missile installations under construction.

The pilot of the aircraft was Major Richard Heyser, flying at an altitude of around 70,000 feet, far above the range of Cuban or Soviet air defenses. The aircraft he was flying was the Lockheed U-2, a high-altitude reconnaissance plane designed to avoid radar detection and gather photographic intelligence over enemy territory. The mission had been carefully planned, part of a series of surveillance flights meant to verify reports of increasing Soviet military presence in Cuba.

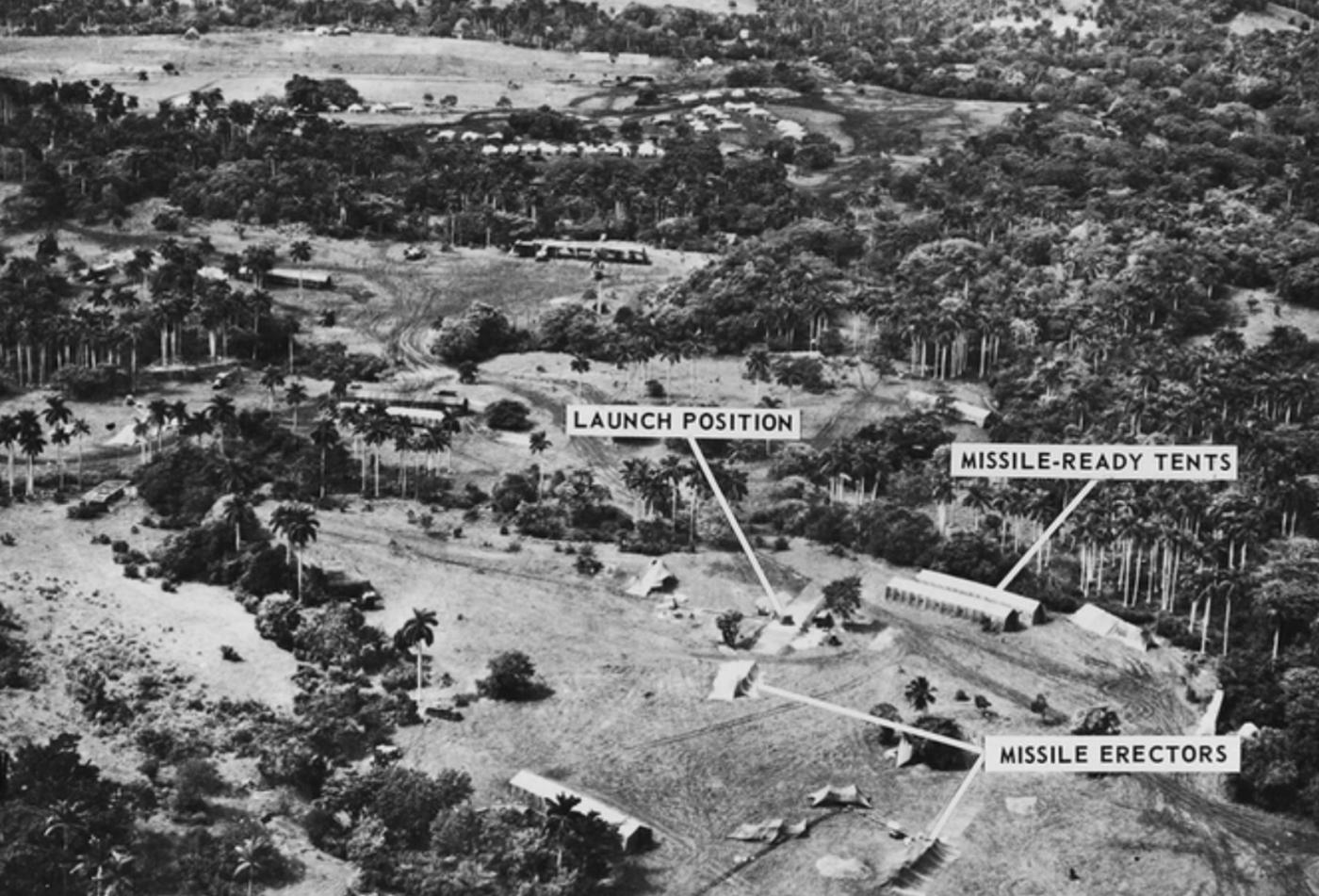

When Heyser returned with his film, analysts at the National Photographic Interpretation Center in Washington, D.C., began their meticulous review. Within hours, they identified long, canvas-covered missiles, support vehicles, and launch pads at a site near San Cristóbal in western Cuba. These were SS-4 medium-range ballistic missiles, capable of carrying nuclear warheads to much of the eastern United States within minutes. It was now irrefutable: the Soviet Union, under Nikita Khrushchev, was actively installing nuclear weapons just 90 miles from American shores.

The implications were staggering. The United States had long been concerned about Soviet intentions in the Western Hemisphere, but this was a direct challenge. President John F. Kennedy was informed of the discovery on the morning of October 16, and over the next several days, he convened a group of senior officials and advisors known as the Executive Committee of the National Security Council, or ExComm. Their task: determine how to respond to this extraordinary threat without triggering a nuclear war.

Among the most forceful voices in the early days of the crisis was General Maxwell Taylor, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. He, along with many military leaders, advocated for immediate and decisive action, including airstrikes against the missile sites and even a full-scale invasion of Cuba. Their argument was clear: allowing the missiles to become operational would fundamentally shift the strategic balance of power in favor of the Soviet Union and make the U.S. vulnerable to a first strike.

Others within ExComm, notably Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara and Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, urged caution. They feared that a military strike could provoke a Soviet response in Berlin or even lead to a global nuclear exchange. After intense debate, President Kennedy opted for a middle course. On October 22, he addressed the nation in a televised speech, revealing the presence of Soviet missiles in Cuba and announcing the imposition of a naval "quarantine" to prevent further delivery of weapons to the island.

The decision to use the term "quarantine" instead of "blockade" was deliberate—blockades are considered acts of war under international law, and Kennedy was determined to avoid pushing the situation into open conflict. Over the following days, the world watched anxiously as U.S. Navy ships established a perimeter around Cuba and Soviet vessels carrying missile components approached the quarantine line.

Behind the scenes, a tense diplomatic standoff unfolded. Messages passed between Washington and Moscow, some conciliatory, others threatening. The crisis reached its peak on October 27, when another U-2 was shot down over Cuba and its pilot, Major Rudolf Anderson, was killed. Despite this escalation, cooler heads prevailed. The next day, Khrushchev agreed to dismantle the missile installations in exchange for a public U.S. pledge not to invade Cuba and a secret agreement to remove American Jupiter missiles from Turkey.

The reconnaissance flight by Major Heyser on October 14 was the spark that brought the hidden Soviet buildup into the light. Without it, the missiles might have become operational before the United States could react. The discovery set off thirteen days of unparalleled tension, where the threat of nuclear war loomed over the globe. In the end, the crisis was resolved through a mixture of resolve, restraint, and back-channel diplomacy—preventing catastrophe, but forever altering the nature of the Cold War.