Claymore Mine

The Claymore antipersonnel mine occupies a particular place in modern military history because it represents a shift away from buried, indiscriminate mines toward a weapon designed to be directional and deliberately controlled. Most people encounter it first as a name, or as a prop in films and games, but its real-world origins lie in Cold War military thinking and the search for more predictable ways to defend positions and control movement on a battlefield.

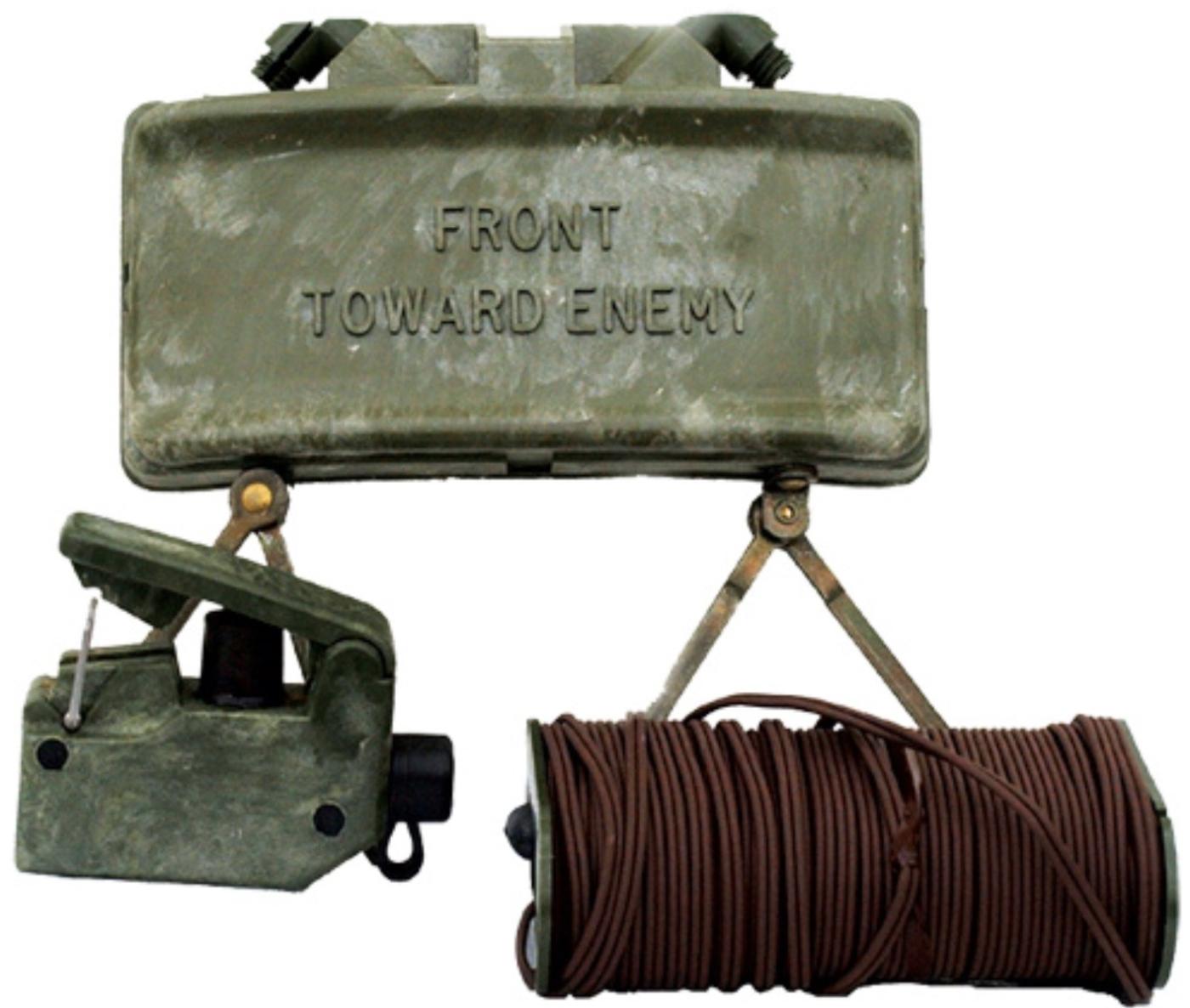

The best-known version, the M18A1 Claymore, was developed in the United States during the 1950s and formally adopted by the United States Army. Rather than being triggered by someone stepping on it, the Claymore was conceived as a command-detonated device, meaning it would be set up, aimed, and fired intentionally by a soldier. Its curved rectangular shape reflects its core design idea: to focus its effect in a specific direction instead of spreading it randomly in all directions. Even its name is symbolic, taken from the Scottish two-handed sword, which reinforces the idea of a single, forward-facing strike.

There is no single famous inventor behind the Claymore. It emerged from institutional military research and ordnance development rather than from an individual designer. Earlier concepts of directional explosives and fragment projection already existed, but the Claymore was the first widely standardized and mass-issued version of this idea. Once adopted, it became a standard item in U.S. inventories and influenced similar designs elsewhere.

Manufacturing followed the usual pattern for military equipment of the era. Production was handled by defense contractors working under government contracts, rather than by a single permanent manufacturer. Over time, other countries developed their own Claymore-type devices or close copies, sometimes with small changes in materials or external appearance. As a result, the term “Claymore” is often used generically, even though many similar devices were produced outside the United States.

The Claymore became especially well known during the Vietnam War period, when it was widely issued and frequently mentioned in soldiers’ accounts. Its reputation grew because it fit the realities of jungle warfare and base defense, where forces wanted a way to cover likely approaches without scattering explosives indiscriminately across the ground. This association cemented its place in military lore and later in popular culture.

Estimating how many Claymores have been used worldwide is difficult. Procurement figures exist for certain periods and countries, but there is no comprehensive global total. What is clear is that they were produced in large numbers over several decades, used in training as well as in combat, and stockpiled by multiple militaries. Some remain in inventories today, while others have been destroyed or restricted under changing policies on antipersonnel weapons.

At a conceptual level, the Claymore’s internal design combines an explosive element with preformed fragments and a casing shaped to bias the force outward in one direction. The result is a concentrated zone of danger rather than an all-around blast. Injuries caused by fragmentation weapons are often severe, involving multiple penetrating wounds and long-term disability for survivors, which is why devices of this type are so controversial despite their controlled intent.

That controversy feeds directly into international humanitarian debates. Traditional buried antipersonnel mines are notorious for remaining active long after conflicts end, killing and maiming civilians who were never part of the fighting. A Claymore used strictly as a command-detonated device does not create the same lingering hidden hazard, because it is not meant to be left behind to be triggered by chance. However, if adapted for victim activation or abandoned, it crosses into the same ethical and legal problem space as other antipersonnel mines. This distinction has led to careful language in international agreements and national policies, with some states restricting or banning victim-activated mines while still allowing tightly controlled directional munitions.