British Rationing

Few objects capture everyday life on Britain’s home front during the Second World War as powerfully as the ration book. More than a simple booklet, it governed what people ate, wore, and used from week to week. Rationing affected everyone—men, women and children alike—and reshaped daily routines in homes, shops, farms, and streets across the country.

When war broke out in 1939, Britain faced a serious and immediate problem. The nation depended heavily on imported food, bringing in around 55 million tonnes each year from across the world. German submarine attacks on shipping routes quickly threatened these supplies, prompting widespread fear of shortages, hoarding, and soaring prices. The government feared that without strict control, food would become unevenly distributed, leaving the poorest at greatest risk.

To prevent this, rationing was introduced not simply as a way to limit consumption, but as a system designed to ensure fairness. Behind the scenes, scientists at the University of Cambridge carried out a top-secret experiment to determine whether a diet based largely on British-grown food could sustain the population. Their findings showed that even with limited imports, people could remain healthy and strong, providing the scientific confidence behind the rationing system that followed.

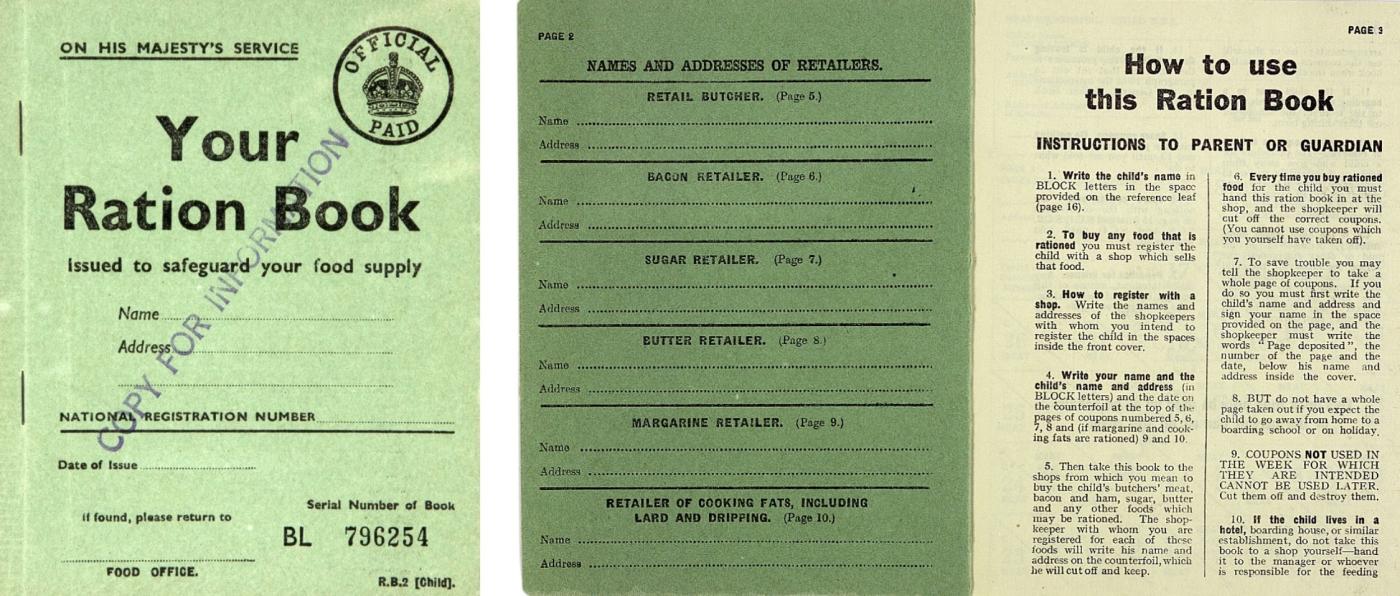

In January 1940, ration books were issued to every person in Britain. Each book contained pages of printed coupons, carefully organised and dated, which could only be used during specific weeks or months. These coupons had no value on their own; they only became valid when torn out and exchanged for goods at registered shops. Shoppers were required to bring their ration books with them, and shopkeepers would physically cut out or tear off the correct coupons at the counter before handing over the goods.

People could not shop wherever they pleased. Every individual had to register with a specific butcher and greengrocer, and later with other food retailers as rationing expanded. This registration was recorded in both the ration book and the shopkeeper’s records. The system allowed shopkeepers to know exactly how many customers they were responsible for supplying, helping them order the correct quantities and reduce waste. It also prevented people from visiting multiple shops to obtain extra rations.

Shopping became a carefully planned activity. Households studied their ration books in advance, deciding how best to use their monthly points. Some foods were more “expensive” in coupons than others, meaning families had to weigh up whether an item was worth the cost. If a shop had run out of a particular product, coupons could not simply be used elsewhere, leaving shoppers disappointed but resigned. Queues were common, and people often waited without knowing whether supplies would last until their turn.

Meat was the first food to be rationed, followed by fats, sugar, cheese, and many other staples. Unlike point-based foods, meat was limited by weight, meaning the amount available could vary week by week. Some cuts became rare luxuries, and offal and unfamiliar substitutes grew more common. Shopkeepers often offered creative alternatives, and recipes were shared to make the most of limited ingredients.

Different ration books were issued depending on age and circumstance. Adults carried brown ration books, while green books were given to pregnant women, nursing mothers, and young children, providing extra allowances of foods such as milk. Blue ration books were issued to older children, reflecting their growing nutritional needs. Ration books were precious items, and losing one could be a serious problem, requiring official replacement and investigation.

Rationing extended far beyond food. Petrol was rationed using small green coupon books, with each coupon worth one gallon of fuel and valid only for a short period. Clothing rationing, introduced in 1941, limited the number of garments people could buy and encouraged mending, remaking, and sharing. Clothes labels often displayed their coupon value, and many families carefully saved coupons for essential items such as winter coats or shoes.

On farms, rationing transformed agriculture. Production was tightly controlled, and even animal feed was rationed to maximise efficiency. Farmers needed official permission to slaughter animals, and produce was carefully accounted for. With many men serving in the armed forces, women filled vital roles through the Women’s Land Army, learning new skills and keeping food production going under intense pressure.

Rationing also exposed differences between town and countryside. Rural families often had access to gardens, land, or livestock that provided extra food outside the official system, while urban families relied almost entirely on their ration books. For some, even rationed food was difficult to afford, showing that rationing did not automatically guarantee equality. Evacuation sometimes changed diets dramatically, as city children encountered fresh milk, eggs, and vegetables for the first time.

Although the war ended in 1945, rationing remained a feature of daily life for almost another decade. Britain’s weakened economy, reduced overseas aid, and a desire to support starving populations in Europe all contributed to its continuation. Meat was the last food to be derationed in 1954, making Britain the final major wartime nation to abandon food rationing.

When rationing finally ended, it was celebrated publicly, symbolising a return to choice and abundance. Yet for those who lived through it, ration books remained powerful reminders of a time when shopping meant planning, patience, and sacrifice, and when a small booklet of coupons shaped almost every aspect of daily life.