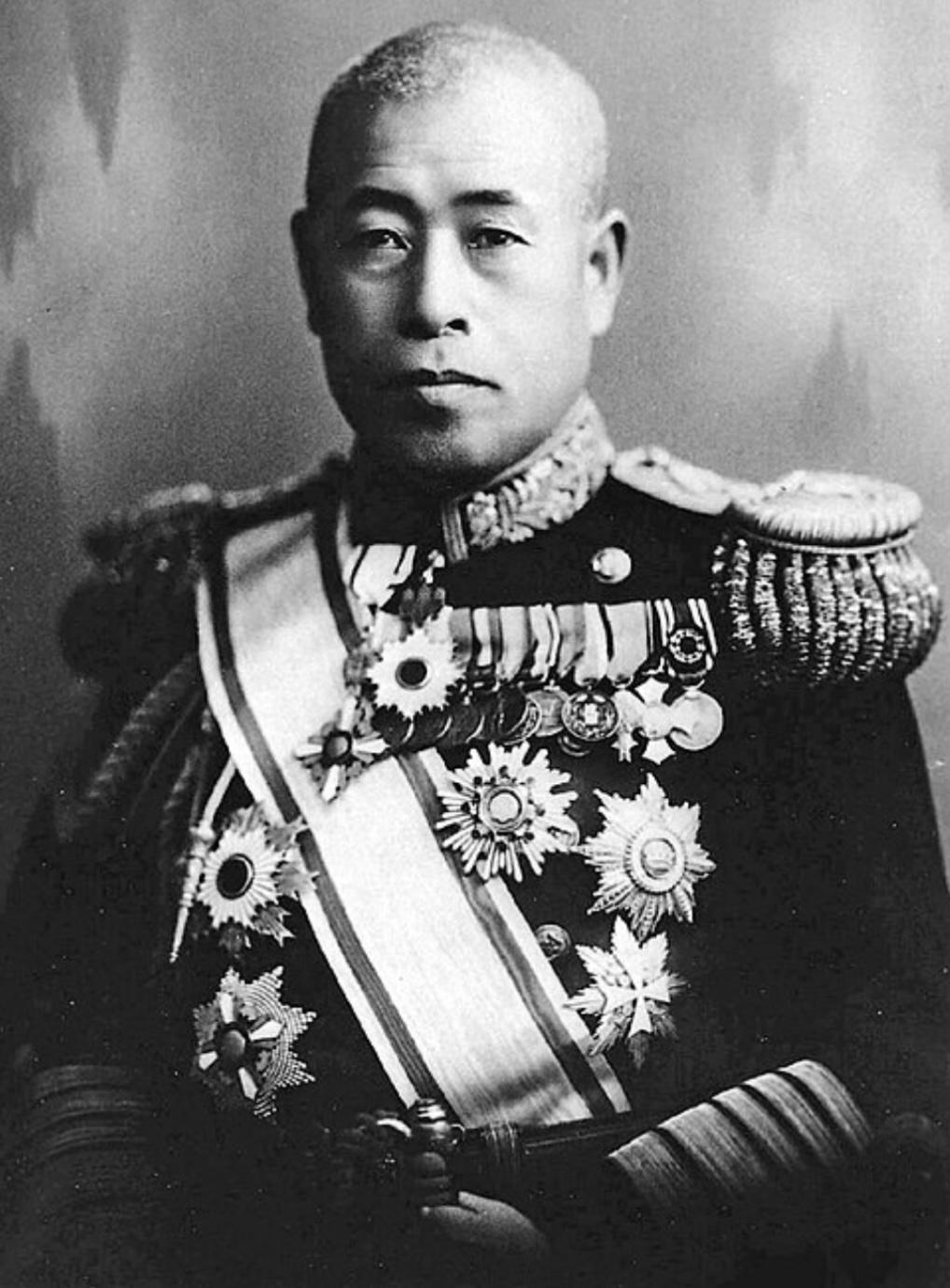

Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto

Isoroku Yamamoto was born on April 4, 1884, in Nagaoka, a small castle town in Niigata Prefecture. He was the sixth son of a modest samurai family that had fallen on hard economic times after the Meiji Restoration. Originally named Isoroku Takano, meaning “56” to indicate his father’s age when he was born, he was later adopted by the Yamamoto family, a common practice in Japan for preserving samurai lineages. His early life was shaped by a strict and disciplined environment, and he showed a keen mind, particularly in mathematics and literature. Although physically small and plagued by recurring health issues as a child, he developed a stubborn determination and a lifelong sense of purpose.

Yamamoto entered the Imperial Japanese Naval Academy and graduated in 1904, just in time for the Russo-Japanese War. He served aboard the cruiser Nisshin during the conflict and was wounded at the Battle of Tsushima, losing two fingers on his left hand. Instead of being a setback, this injury became a source of pride for him, symbolizing sacrifice and commitment. It also earned him the nickname “80 sen Admiral,” referring to the cost of losing eight-tenths of a hand, a lighthearted joke among sailors. After the war, Yamamoto began a steady climb through the ranks. His superiors quickly recognized him as exceptionally intelligent, fluent in English, and unusually open-minded for an officer of his generation.

In 1919, he was selected to study in the United States at Harvard University. This time transformed him. He traveled extensively across America, observing its industry, economy, and culture, and gaining a deep respect for the nation’s potential. He believed that a war against the United States would be disastrous for Japan. Upon returning home, he became a key figure in naval aviation, an area many traditionalists in the Japanese Navy dismissed. Yamamoto saw aviation as the future of naval warfare, arguing that aircraft carriers and air power would eclipse battleships. His ideas clashed with conservative factions in the Navy, but his strategic brilliance and persistence gradually earned him influence.

During the 1930s he opposed Japan’s drift toward militarism and its alliance with Nazi Germany. He spoke openly against war with the United States, which made him a target for right-wing extremists. The only reason he survived several assassination plots was that the Navy leadership transferred him frequently and provided heavy protection. In 1939, he was appointed Commander-in-Chief of the Combined Fleet, giving him supreme operational authority over Japan’s naval forces. This rise was due to his remarkable strategic mind, loyalty to the Navy, and the respect he commanded from both reformers and moderates.

As commander, Yamamoto oversaw the planning and execution of the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941. Despite opposing the war itself, he believed that if Japan had to fight, the opening blow must be overwhelming. His tactics relied on surprise, precision, and the mobility of carrier-based fleets. Yamamoto understood that Japan could not win a prolonged war and hoped a shocking attack would force the United States into negotiation rather than total war. His strategy demonstrated both originality and realism, though ultimately it underestimated American resolve.

Throughout the war, Yamamoto continued to advocate for aggressive, high-risk operations designed to exploit Japan’s early advantages. He orchestrated the expansion across the Pacific during the first months of the conflict and oversaw plans that led to major battles such as the Coral Sea and Midway. Midway in particular was a turning point. Yamamoto’s plan was complex, relying on deception and coordination across a vast distance, but American codebreakers intercepted key communications. The resulting defeat devastated Japan’s carrier fleet, and Yamamoto privately accepted responsibility. Despite the setback, he retained command because of his leadership, prestige, and the loyalty he inspired in the fleet.

Yamamoto was known for his personal discipline, love of poetry and calligraphy, and his fondness for poker and gambling, which sharpened his understanding of risk and probability. He maintained a simple lifestyle even as a high-ranking officer and was admired for his fairness and humanity toward subordinates. Yet he was also stern, demanding absolute precision from his crews and expecting them to match his own high standards of duty.

On April 18, 1943, his life came to an abrupt end. American intelligence decrypted a message detailing Yamamoto’s inspection tour of the Solomon Islands. In one of the most targeted operations of the war, U.S. Army Air Forces P-38 fighters intercepted his aircraft over Bougainville and shot it down. Yamamoto died instantly, still strapped into his seat. His death was a major psychological blow to Japan, which mourned him as a national hero and symbol of naval strength. The Americans viewed the operation, codenamed “Vengeance,” as strategic justice for Pearl Harbor.

Isoroku Yamamoto remains one of the most complex and studied figures of the Second World War. He was a visionary who foresaw the power of naval aviation, a reluctant warrior who opposed the very conflict he helped initiate, and a commander whose brilliance was ultimately constrained by the political forces and strategic realities of his time. His life reflects both the rise of Japan’s modern navy and the tragedy of a nation swept into a war it could not win.