U-Boat Schnorchel

The snorkel, spelled “Schnorchel” in German usage, was one of the most significant late-war adaptations fitted to German submarines and fundamentally changed how U-boats operated while submerged during the Second World War. Its purpose was simple but revolutionary: to allow a submarine to run its diesel engines while below the surface, drawing in fresh air and expelling exhaust gases without having to fully surface and expose itself to enemy aircraft and radar.

Before the snorkel, German U-boats were essentially surface ships that could submerge for short periods. Their diesel engines, which provided speed and range, required large quantities of air and could only be used on the surface. Once submerged, boats had to rely on electric motors powered by batteries. These batteries drained quickly, forcing submarines to surface regularly to recharge, often at night. By 1942–1943, Allied air patrols, radar, and radio direction finding made surfacing increasingly dangerous, turning battery recharging into one of the most lethal moments of a patrol. The snorkel was introduced as a direct response to this crisis.

The idea was not originally German. Early concepts appeared in the Netherlands before the war, and when Germany occupied the country in 1940, the technology fell into German hands. Engineers within the Kriegsmarine quickly recognized its potential. Further development was driven by submarine designers and specialists such as Hellmuth Walter, who were already exploring ways to keep submarines underwater for longer periods. By 1943, experimental installations were being tested, and by 1944 the Schnorchel began to appear widely on operational boats, especially the Type VII and Type IX classes.

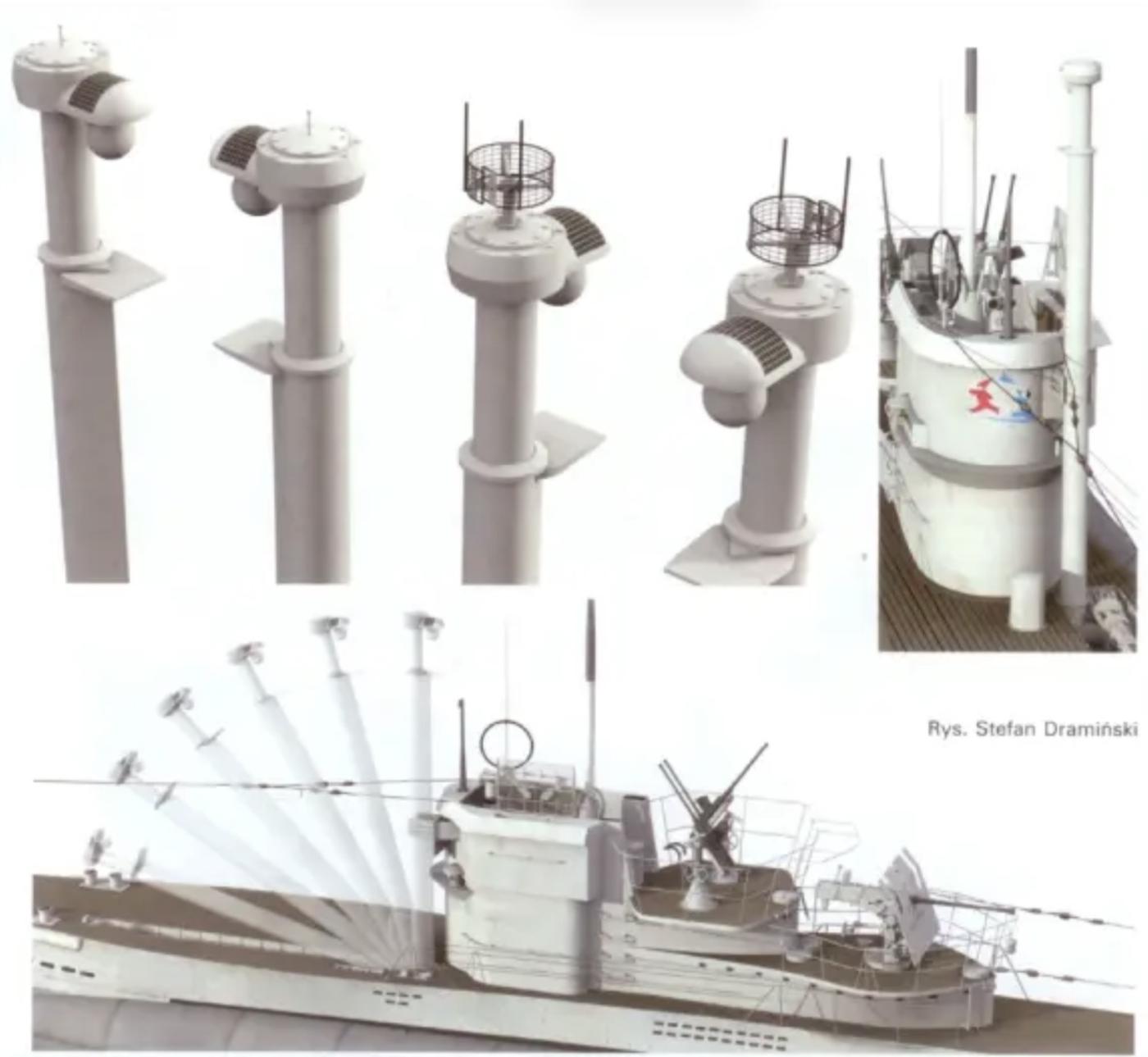

Physically, the snorkel was a retractable mast mounted on the submarine’s hull, usually on the starboard side of the conning tower. When not in use, it folded down into a recessed housing and lay flush against the deck or tower, minimizing drag and reducing the risk of damage from waves or enemy fire. When needed, the mast could be raised hydraulically or mechanically from inside the boat. Once extended, it projected just a short distance above the surface, often little more than a meter, making it far harder to spot than a fully surfaced submarine.

The mast itself usually consisted of two main channels: one for intake air and one for exhaust gases from the diesel engines. At the top was a head valve, sometimes called a float valve, which automatically closed if waves washed over the opening. This prevented seawater from flooding down into the boat. When the valve snapped shut, however, the diesel engines continued to draw air, creating a sudden vacuum inside the submarine. This could cause ear pain, nosebleeds, and intense discomfort for the crew, and it was one of the most disliked aspects of snorkel operation. Engines often had to be throttled back or shut down temporarily until the valve reopened.

Using the snorkel imposed strict limitations on speed and maneuverability. While running on diesel with the mast raised, a U-boat could typically make only about 5 to 6 knots. Higher speeds increased vibration and exhaust pressure, making detection more likely and stressing the snorkel mast. The extended mast also added drag and affected handling, especially in rough seas. In heavy weather, waves could repeatedly close the head valve, making sustained diesel operation almost impossible and forcing the submarine back onto batteries.

There were also serious detection risks. Although the snorkel reduced visual exposure, it did not make submarines invisible. Allied radar sets were eventually refined enough to detect the small radar cross-section of a snorkel head, especially in calm seas. Exhaust gases sometimes left a faint wake or smell detectable by aircraft crews. Additionally, diesel engines running underwater were noisy, and the vibrations transmitted through the hull could be picked up by Allied sonar, sometimes making a snorkeling submarine easier to track than one running silently on electric motors.

Despite these drawbacks, the Schnorchel dramatically improved U-boat survivability. It allowed submarines to remain submerged for days or even weeks at a time, drastically reducing the need to surface. Crews could recharge batteries, ventilate the boat, and make long transits while staying below the surface, something that would have been unthinkable earlier in the war. In effect, it marked the transition from the early “surface-oriented” submarine to a true underwater vessel.

By the final year of the war, the snorkel was standard equipment on most German submarines and heavily influenced postwar submarine design worldwide. Although introduced too late and in too small numbers to reverse Germany’s fortunes in the Battle of the Atlantic, the Schnorchel was a clear acknowledgment that air power and radar had changed naval warfare forever. It remains one of the most important incremental innovations in submarine history, bridging the gap between conventional diesel-electric boats and the fully submerged nuclear submarines that would follow in the decades after the war.