Plank Road

The Western Front of the First World War was notorious for its mud — not merely wet fields, but vast stretches of liquid ground where a man could sink to the waist and horses drowned almost silently. Artillery dominated the war, yet a gun was only as useful as the ability to move and supply it. The Canadian Corps, like all major armies, learned quickly that mobility depended less on wheels and horsepower than on carpentry. Plank roads — quickly assembled timber trackways — became one of the most essential but least glamorous tools of engineering warfare.

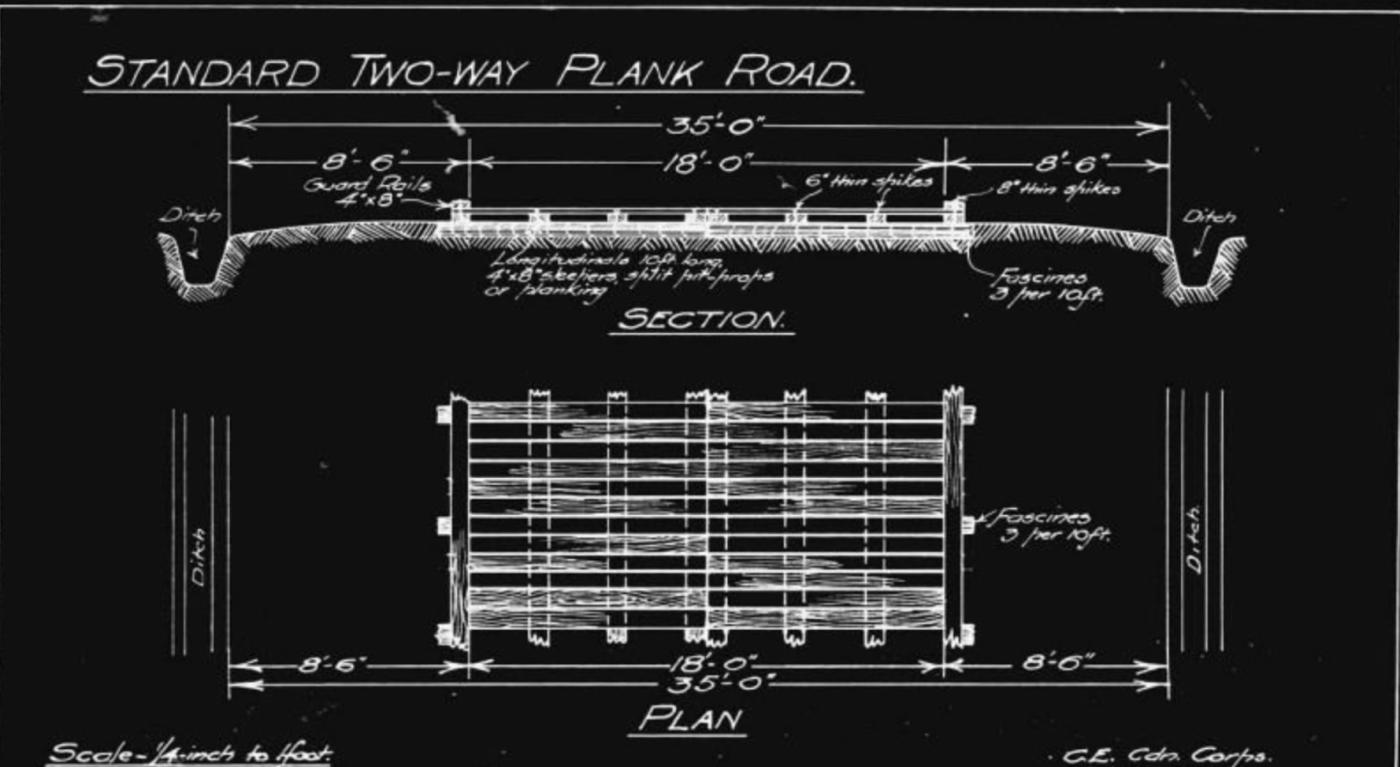

A plank road was built to lie on top of the ground rather than cut through it. In its simplest form it began with a base of corduroy — whole logs or rough-hewn trunks laid crosswise directly onto the mire, purely to keep the next layer from vanishing into the bog. Where timber supply or time permitted, that foundation was improved with rubble, sandbags or short oak sills to firm the base. Onto that went the structural spine of the road: long timbers known as stringers, running in the direction of traffic and spaced so that a gun’s wheels would fall squarely upon them. These carried the weight. Across the stringers the working surface was laid — thick sawn planks, usually 3 to 6 inches thick, laid horizontally and spiked or trenail-fixed in a staggered pattern so that joints did not line up.

To move an 18-pounder gun — roughly a ton in motion when limbered with ammunition — the road had to bear concentrated loads without splitting or sagging. Engineers therefore reinforced the wheel paths with double planking or additional longitudinal members where needed. Everything was fastened tightly so the structure behaved like a single flexible beam rather than a series of loose boards. In the wettest sectors, crews nailed wire mesh, rope or cleats to the running planks to give grip for horses. Everything was modular; men carried fresh pieces forward, bolting or spiking them on as the road advanced almost with the army.

The wood itself was nearly always softwood — spruce and pine above all — because Canadian forestry units could fell, mill and move immense quantities of it quickly. Hardwoods such as oak were used when available for the stringers or foundation sills in high-stress sections, but durability mattered far less than speed and tonnage. These roads were expected to be chewed up, repaired and replaced constantly. Men walked behind the advance with fresh planks over their shoulders, replacing shattered or submerged sections almost as fast as artillery and supply wagons broke them.

In operation a good plank road transformed a battlefield. Where a wheeled limber would otherwise sink up to its hubs, it could now roll — slowly, creakingly, but steadily — along a continuous timber surface that spread weight across dozens of supports. Even in pitch darkness or shell-churned rain, pioneers could extend these roads forward, linking supply dumps to gun positions and gun positions to assembly lines. Across Vimy, Passchendaele and later operations, entire offensives depended on completing these plank routes before the attack — sometimes more urgently than the stockpiling of ammunition itself.

They were never intended to last. They rotted, they splintered, they were buried by shellfire and rebuilt the same night. But their logic was perfect: raise the load above the water, distribute weight over many points, give wheels a continuous track that resists suction. Without them, an 18-pounder field gun might as well have been nailed to the mud. With them, the Canadian Corps — soaked, freezing, but relentlessly practical — could make the impossible merely miserable, and still keep moving forward.