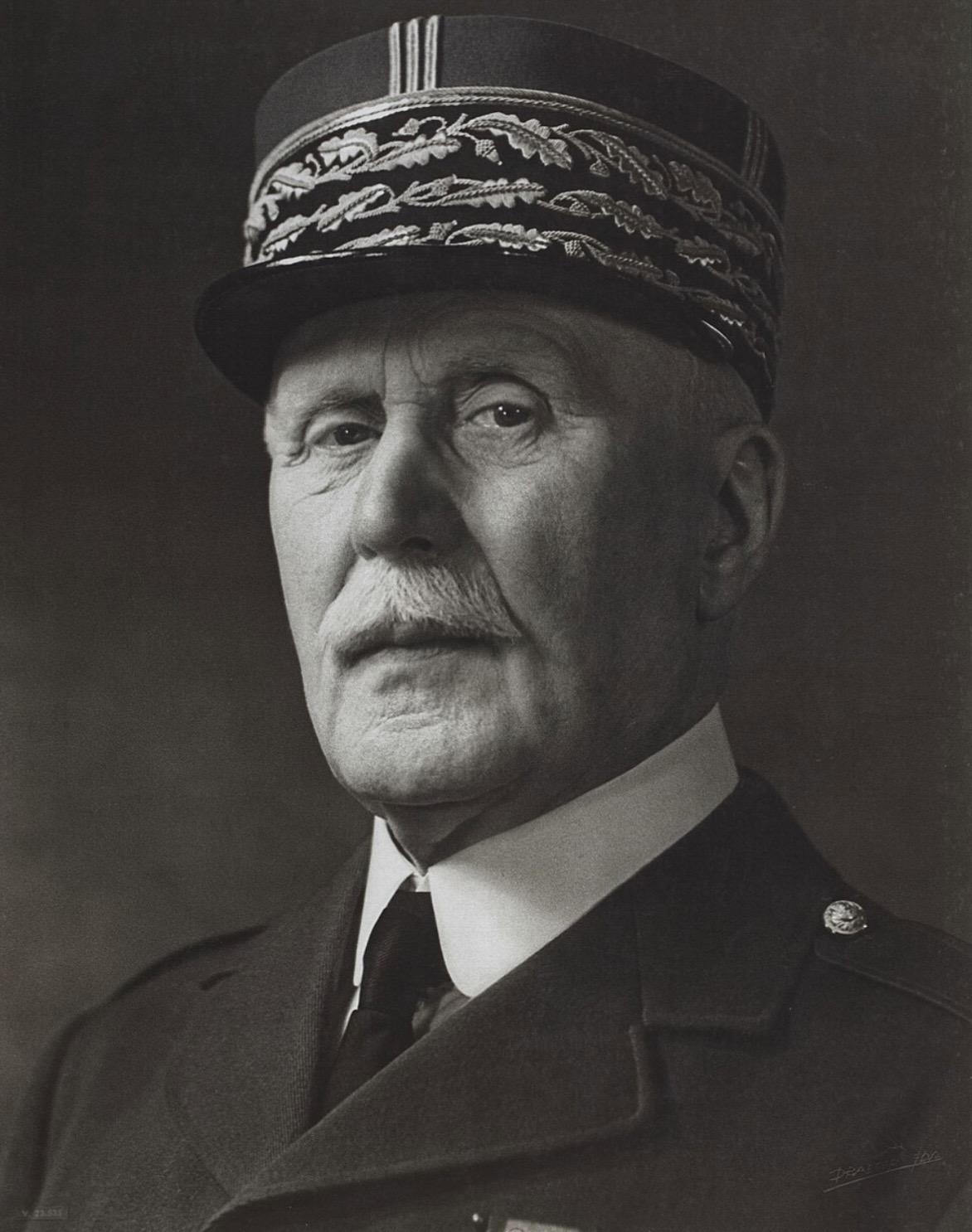

Philippe Petain

Philippe Pétain was born on 24 April 1856 in the small village of Cauchy-à-la-Tour in northern France. He came from a modest farming family and spent his early years in a rural environment shaped by traditional Catholic values and conservative social attitudes. As a young boy he witnessed the aftermath of the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–1871, in which France suffered a humiliating defeat. This experience deeply affected the generation he belonged to and influenced his later commitment to rebuilding France’s military strength and national pride.

Pétain entered the French military academy at Saint-Cyr in 1876. Unlike many of his contemporaries, he did not initially stand out as a brilliant officer and his career progressed slowly. He served in various infantry regiments and became known for his serious, methodical approach rather than flamboyant leadership. During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the French army often promoted officers who embraced aggressive offensive tactics, while Pétain advocated careful planning, defensive strength, and the importance of artillery support. These views made him somewhat unfashionable in the army at the time and delayed his advancement.

He spent years teaching at military schools, including the École de Guerre, where he gained a reputation as a thoughtful strategist. By the time the First World War broke out in 1914, Pétain was already 58 years old and a colonel, an age at which many officers were nearing retirement. However, the massive expansion of the French army during the early months of the war created opportunities for capable commanders, and Pétain quickly proved his worth.

In the early stages of the war he led a brigade and then a division with notable competence, particularly during the First Battle of the Marne in 1914. His calm leadership and effective use of artillery earned him promotion to general. He soon commanded the XXXIII Corps and then the Second Army. His emphasis on coordination between infantry and artillery and his insistence on conserving soldiers’ lives made him popular among troops, who respected commanders who seemed to care about their survival in the brutal trench warfare of the Western Front.

Pétain’s greatest fame came during the Battle of Verdun in 1916, one of the longest and most devastating battles of the war. When German forces launched a massive offensive against the fortress city of Verdun in February 1916, Pétain was placed in charge of French forces defending the area. He organised a determined defensive strategy that relied heavily on artillery and constant reinforcement. One of his key innovations was maintaining the “Voie Sacrée,” a vital supply road that allowed a continuous rotation of troops and supplies into the battlefield. This ensured that exhausted units could be replaced and morale maintained.

Under his command, the French army held Verdun despite enormous casualties. Pétain became a national hero, celebrated for his steady leadership and for preventing a catastrophic defeat. His reputation as the “saviour of Verdun” made him one of the most respected figures in France. Later in 1917, after widespread mutinies broke out in the French army following disastrous offensives and heavy losses, Pétain was appointed commander-in-chief of the French forces. Rather than relying on harsh repression alone, he restored discipline through a combination of limited punishments and reforms. He improved soldiers’ living conditions, increased leave, and promised to avoid futile offensives. His approach successfully stabilised the army and prepared it for the final Allied offensives of 1918.

When the First World War ended in November 1918 with Allied victory, Pétain was widely regarded as one of France’s greatest military leaders. He was promoted to Marshal of France in 1918, the country’s highest military honour. In the years after the war he served in various senior roles, including vice-chairman of the Supreme War Council and inspector general of the army. He supported defensive strategies and the construction of the Maginot Line, a vast system of fortifications along France’s eastern border designed to prevent another German invasion.

As he aged, Pétain’s political views became more conservative and authoritarian. He admired order, discipline, and traditional values, and he grew increasingly critical of parliamentary democracy, which he saw as weak and divisive. Despite his age, he remained a revered national figure throughout the interwar period.

When the Second World War began in 1939, Pétain was already in his eighties and serving as French ambassador to Spain. After Germany invaded France in May 1940 and the French military collapsed, he was called back into government as deputy prime minister. As German forces advanced rapidly and Paris fell, many French leaders believed further resistance was hopeless. Pétain argued for an armistice with Germany to prevent further destruction and loss of life. On 22 June 1940 France signed an armistice with Nazi Germany, effectively ending active resistance.

Shortly afterward, the French parliament granted Pétain full powers to govern. He established an authoritarian regime based in the town of Vichy, which became known as the Vichy government. As Chief of State, Pétain dismantled the democratic Third Republic and replaced it with a regime that promoted conservative, nationalist, and traditionalist values under the slogan “Work, Family, Fatherland.” His government collaborated with Nazi Germany, enforcing anti-Jewish laws, suppressing political opponents, and assisting in the deportation of Jews and other groups to German concentration camps.

Initially, some French citizens supported Pétain, seeing him as the hero of Verdun who might protect France under difficult circumstances. However, as the war continued and collaboration with Germany deepened, his reputation deteriorated. Many French people joined the Resistance, while General Charles de Gaulle led the Free French forces from exile. By 1944, as Allied forces liberated France, the Vichy regime collapsed and Pétain was taken into German custody before eventually being handed over to French authorities.

In 1945 Pétain was put on trial for treason. The proceedings were highly symbolic, reflecting the nation’s need to confront its wartime collaboration. He was found guilty and sentenced to death. However, due to his advanced age and his status as a First World War hero, the sentence was commuted to life imprisonment by Charles de Gaulle, who had become leader of post-war France. Pétain was imprisoned on the Île d’Yeu, a small island off the French Atlantic coast.

He died there on 23 July 1951 at the age of 95. By the time of his death, his legacy had become deeply controversial. Once celebrated as a national hero for his leadership at Verdun, he was later condemned for his role in leading the Vichy regime and collaborating with Nazi Germany. His life remains one of the most complex and debated in modern French history, representing both the heights of military glory and the depths of political disgrace.