Night of the Broken Glass

Kristallnacht, the night of broken glass, took place on 9–10 November 1938 and marked a decisive turning point in Nazi Germany’s persecution of Jews. The immediate pretext was the assassination of German diplomat Ernst vom Rath in Paris by Herschel Grynszpan, a 17-year-old Polish Jewish refugee whose family, like thousands of others, had just been expelled from Germany and left stranded at the border. Joseph Goebbels, Nazi minister of propaganda, seized on the assassination as the excuse Adolf Hitler had been waiting for. At a gathering of senior Nazi officials in Munich on the evening of 9 November, Hitler gave implicit approval for violent action. Goebbels then stood and encouraged the assembled party leaders to allow “spontaneous” reprisals by the German public. It was in reality a centrally directed operation. Orders were relayed that night to storm trooper (SA) and SS units, as well as the Gestapo and local Nazi officials. Police were explicitly instructed not to interfere, except to arrest Jews if possible.

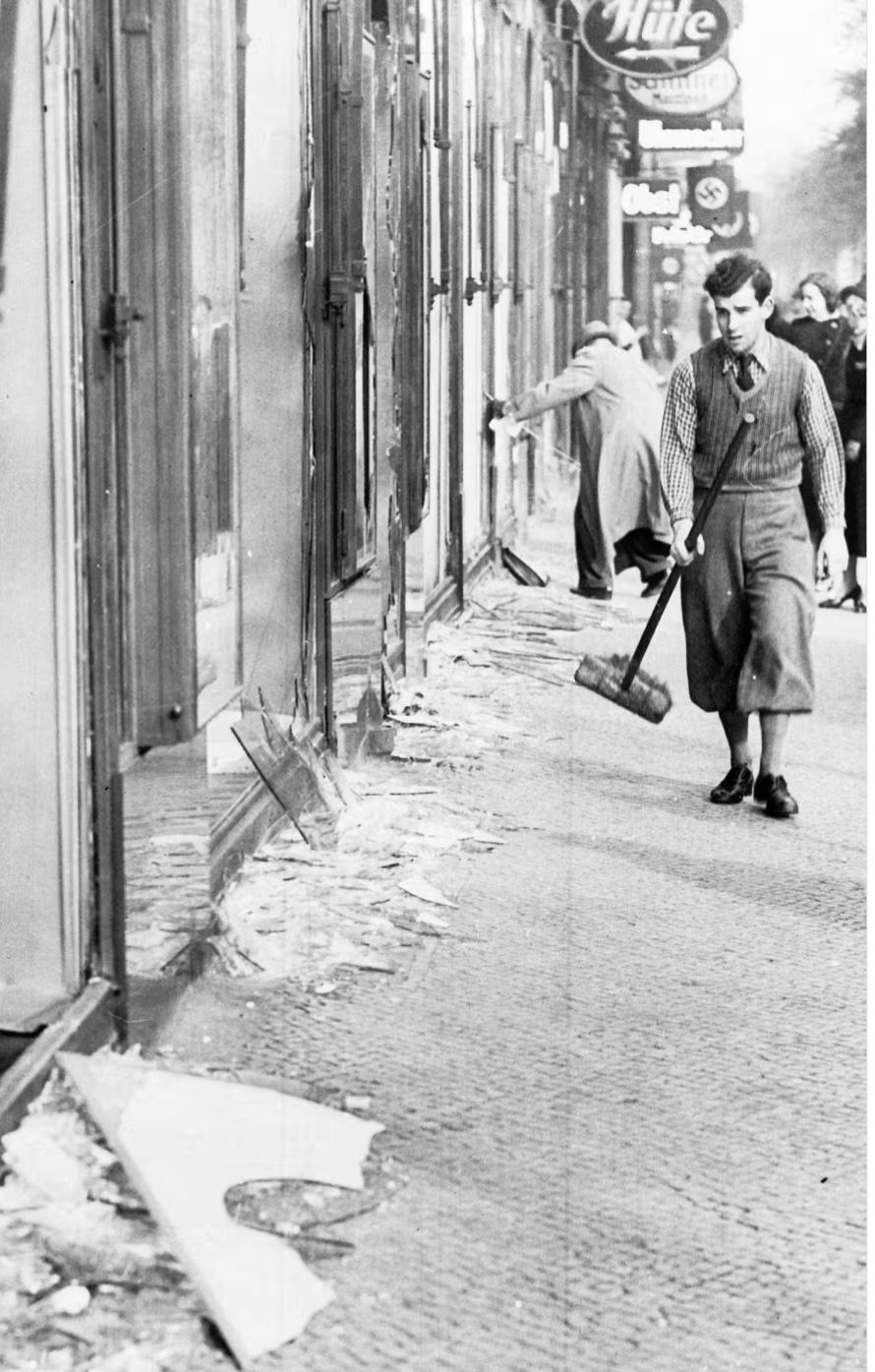

The violence began within hours and spread rapidly across Germany, annexed Austria and the Sudetenland. Around 7,500 Jewish-owned shops and businesses had their windows smashed and interiors ransacked or looted. Approximately 1,400 synagogues and prayer halls were destroyed or set on fire. Jewish schools, cemeteries, and communal institutions were vandalised. Fire brigades mostly stood by unless German-owned property was at risk. Private homes were attacked too — historians estimate about 30,000 were damaged or invaded. Jewish families were dragged out of their beds, beaten in the streets, humiliated, forced to scrub pavements or sing Nazi songs while being mocked.

The violence was not merely symbolic destruction of property. At least 90 Jews were officially recorded as killed that night, but modern research suggests the real number, including suicides driven by terror afterwards, may be in the hundreds. About 30,000 Jewish men were arrested and sent to concentration camps such as Dachau, Buchenwald and Sachsenhausen, where many suffered brutal treatment and dozens died in the following weeks. Businesses were shattered not only physically but financially, and soon after the pogrom the Nazi regime fined the Jewish population a collective one billion Reichsmarks — punishment for the damage they themselves had suffered. Insurance payouts were confiscated by the state. The total cost of physical destruction alone is estimated in the hundreds of millions of Reichsmarks.

Reactions among the wider German public varied. Some actively participated in looting, encouraged by the opportunity to steal. Others cheered or watched silently. A smaller number were horrified, but fear of the regime kept most from speaking out. There were letters of protest from some church leaders, especially after the camps filled with prisoners, but these were carefully worded and had no effect. Internationally the pogrom caused shock and condemnation, yet foreign governments still did little to open their doors to fleeing Jews.

Kristallnacht was a watershed moment. Until then, many German Jews believed that persecution, though harsh, might eventually ease or could still be endured. After that night, it was clear that the Nazi regime was prepared to use large-scale organised violence and that Jewish life in Germany was no longer safe at any level. Emigration surged among those still able to escape, though opportunities were limited. For the regime, the pogrom was a grim experiment in escalating from legal discrimination to open terror. It foreshadowed the even more radical and murderous policies that would follow during the war.