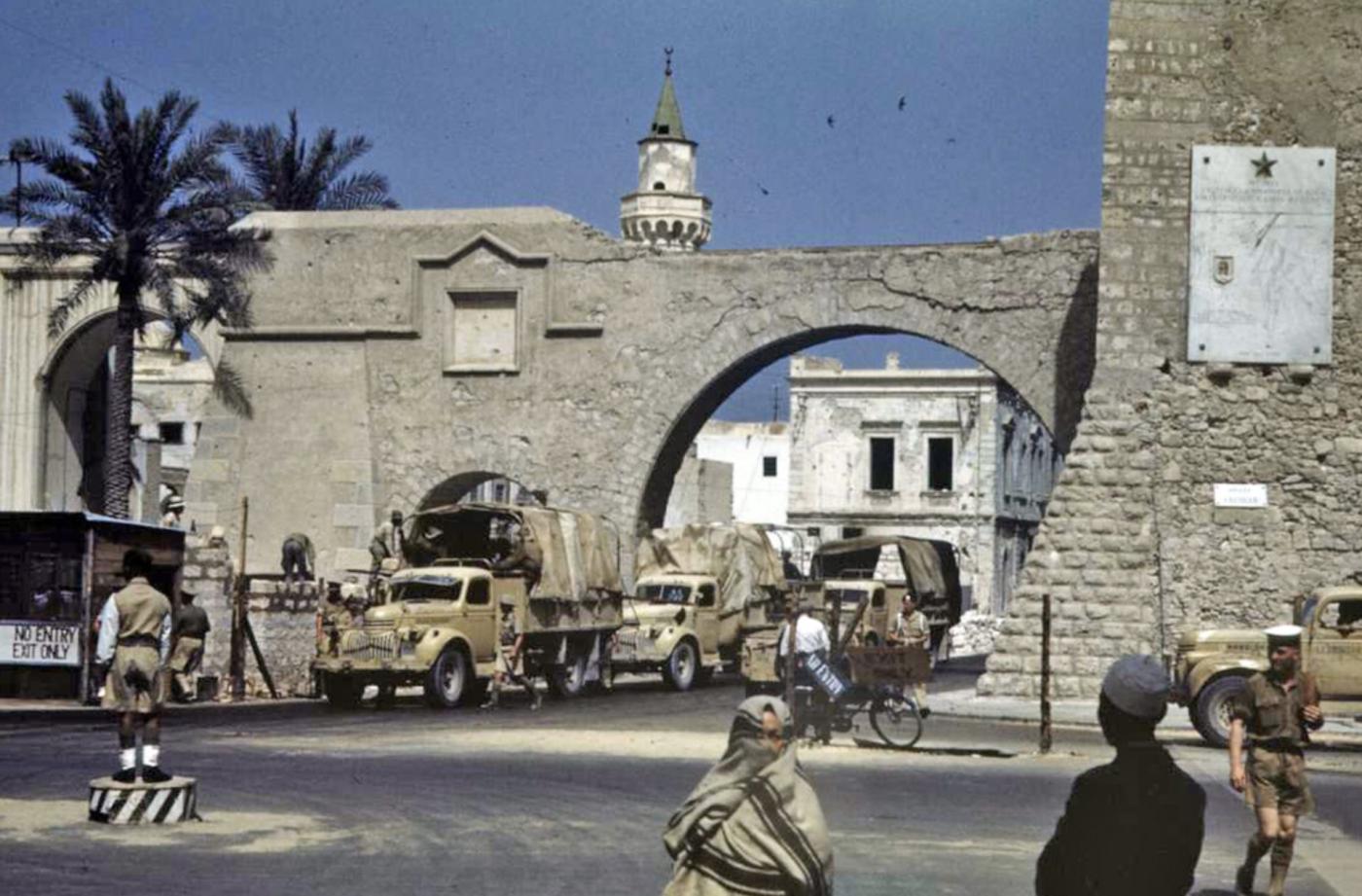

Homs Occupied

the winter of 1943 the war in North Africa was reaching a decisive moment. After their great victory at El Alamein, the British Eighth Army had driven westward across Egypt and Libya in one of the longest pursuits in military history. Rommel’s Afrika Korps, once feared for its speed and striking power, was now in retreat, short of fuel, short of supplies and under constant pressure from British armour and aircraft. By mid-January the chase had carried the Eighth Army almost to the gates of Tripoli, the last major Axis stronghold in Libya.

General Bernard Montgomery knew that the final phase of the Libyan campaign had to be handled carefully. Rommel was still a dangerous opponent, even in retreat, and the German and Italian forces were expert at laying mines, blowing bridges and using small rearguards to delay a larger enemy. Montgomery therefore planned his advance in a way that would deny Rommel time to reorganise or escape inland. Instead of sending all his forces straight along the coast road, he spread them across several routes. Some divisions advanced along the Mediterranean coast, while others pushed through the broken hill country inland. This forced the Axis troops to fall back on a wide front and prevented them from concentrating their defences in one place.

Supplying this advance was a massive undertaking. Every gallon of fuel, every shell and every loaf of bread had to be hauled hundreds of miles across desert roads that were little more than dusty tracks. Long columns of lorries rolled day and night, guided by signs hammered into the sand and by experienced drivers who could find their way even in sandstorms. Without this vast logistical effort the armoured divisions at the front would have been unable to keep moving, and Rommel might have gained the breathing space he needed.

On 19 January 1943 the Eighth Army reached two key points on the approaches to Tripoli: Homs on the coast and Tarhuna in the hills inland. These towns were not heavily defended because the Axis forces were already pulling back toward Tripoli, but their capture was strategically important. Homs brought British troops within little more than sixty miles of the Libyan capital along the main road, while Tarhuna gave them a firm grip on the inland routes that might have allowed Axis units to slip away or mount a counterattack. Together, the two towns formed a tightening grip on Rommel’s retreating army.

The troops who entered Homs and Tarhuna found the signs of a hurried withdrawal. Abandoned vehicles, damaged guns and scattered equipment told the story of an army that was retreating under pressure. German and Italian rearguards had done what they could to slow the British advance, but the momentum was now firmly with the Eighth Army. British armour, supported by artillery and aircraft, was simply too strong for the weakened Axis formations to resist for long.

For the soldiers of the Eighth Army, the occupation of these towns was another step toward a victory that had seemed impossible only months earlier. Many of them had fought all the way from Egypt, across the vast empty spaces of the desert, through heat, cold and exhaustion. Now, as they moved through the narrow streets and stone buildings of Libyan towns, it was clear that the long chase was almost over.

The capture of Homs and Tarhuna had a direct and immediate effect on the campaign. It cut off the last good defensive positions before Tripoli and made it impossible for Rommel to hold the city. Only four days later, British troops entered Tripoli itself, ending Axis control of Libya. This was a huge strategic victory for the Allies. It removed a major Axis base, opened the way for operations into Tunisia, and ensured that the Mediterranean sea routes were far safer for Allied shipping.

In the wider war, what happened on 19 January 1943 was part of a turning of the tide. The Axis powers were now being pushed back on every front, and in North Africa their defeat was only a matter of time. The Eighth Army’s careful planning, its relentless pursuit and its ability to sustain an advance across one of the harshest landscapes on earth had broken Rommel’s army.