Gee & Obe marker systems

During the Second World War the problem of accurately locating and striking a target from the air became one of the central technical challenges of strategic bombing. Crews often flew at night or through cloud to avoid fighters and flak, but this made visual navigation unreliable and bombing accuracy extremely poor. Out of this problem came a series of British electronic navigation and bombing aids, of which GEE and Oboe were among the most important and influential.

GEE was the earlier and more widely used of the two systems. It was developed in Britain by scientists working at the Telecommunications Research Establishment, initially located at Swanage and later at Malvern, under the overall authority of the Royal Air Force. Key figures involved included Robert J. Dippy and Edward G. Bowen, who had already played major roles in radar development before the war. GEE entered operational service in early 1942.

The principle behind GEE was radio hyperbolic navigation. A master ground station in Britain transmitted a timed radio pulse which was immediately retransmitted by two slave stations at known distances from the master. An aircraft equipped with a GEE receiver picked up all three signals. Because radio waves travel at a constant speed, the time difference between receiving the master pulse and each slave pulse could be measured very precisely. These time differences corresponded to lines of position in the form of hyperbolas. By plotting the intersection of two such hyperbolic lines on a special GEE chart, the navigator could determine the aircraft’s position, typically to within a few hundred yards under good conditions.

In practice, the GEE receiver displayed the pulses on a cathode ray tube, and the navigator adjusted a time base until the pulses aligned with calibrated markers. The readings were then converted directly into position using pre-prepared maps. GEE worked best at ranges up to about 350–400 miles from the transmitters, which meant it was highly effective over western Europe but less useful deep into Germany. It was also vulnerable to jamming once the Germans realised how it worked, although countermeasures and frequency changes prolonged its usefulness.

Production of GEE equipment was carried out by British industry, including firms such as Plessey and Marconi. By the end of the war tens of thousands of airborne GEE sets had been built, with most RAF Bomber Command aircraft carrying the system at its peak. It was also supplied to Allied air forces, including the USAAF, though American crews relied more heavily on their own navigation aids.

Oboe was a more specialised and technically sophisticated system, designed to achieve extremely high bombing accuracy rather than widespread navigation coverage. It was also developed at the Telecommunications Research Establishment, with Alec Reeves being one of the central figures behind its concept. Oboe became operational in late 1942 and early 1943.

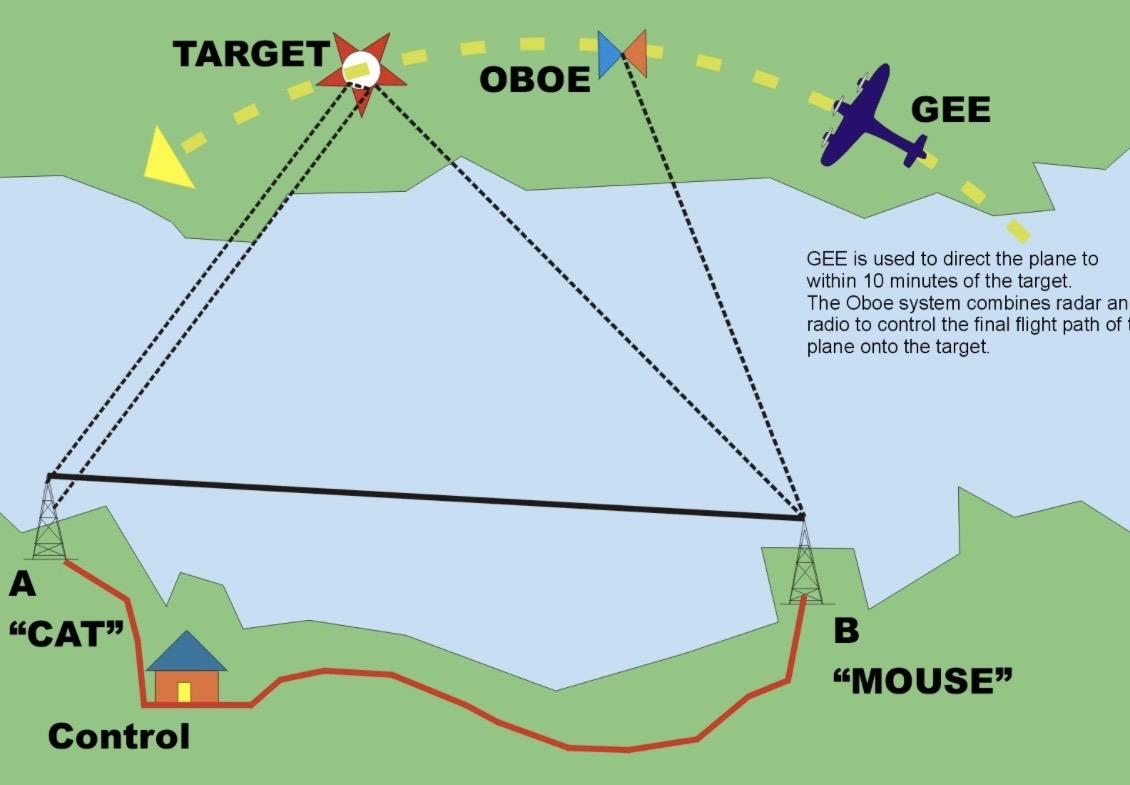

Unlike GEE, Oboe did not allow the aircraft to calculate its own position. Instead, it was a ground-controlled system. Two ground stations in Britain, code-named Cat and Mouse, tracked a single aircraft at a time using precise radio ranging. The aircraft carried a simple transponder that automatically replied to signals sent from the ground. By measuring the round-trip time of these signals, the ground stations could determine the aircraft’s distance from each station with extreme accuracy, often to within a few tens of yards.

The aircraft was guided along a circular arc at a fixed radius from one station. If it drifted inside or outside this arc, the ground controller sent corrective signals to the pilot via audio tones. When the aircraft reached the precise point where the second station’s range corresponded to the target location, a signal was sent that triggered the bomb release automatically or instructed the crew to release immediately. Because all the calculations were done on the ground, the airborne equipment was relatively simple but the system demanded uninterrupted communication and could only control a limited number of aircraft at once.

Oboe’s accuracy was remarkable for its time. Under good conditions bombs could be placed within a few hundred feet of the aiming point, far better than conventional blind bombing methods. However, its range was limited to roughly 270 miles from the ground stations, and its one-aircraft-per-channel nature meant it was mainly used by specialist Pathfinder units rather than by mass bomber formations. Only a few thousand Oboe airborne transponders were produced, reflecting its specialised role, but the ground infrastructure and technical effort behind it were considerable.

The operational impact of GEE and Oboe on bombing missions was profound. Before electronic aids, night bombing accuracy was so poor that only a small percentage of bombs fell within several miles of their intended targets. GEE dramatically improved navigation, reduced losses by helping crews find routes and turning points accurately, and allowed bomber streams to be more tightly controlled. Even when its bombing accuracy was limited by range or jamming, it still helped aircraft reach the correct target area.

Oboe, meanwhile, transformed target marking. Pathfinder aircraft using Oboe could place target indicators with unprecedented precision, allowing following bombers to aim at a clearly defined point rather than a vague area. This was especially important during the Battle of the Ruhr and later attacks on industrial and transportation targets in western Germany and occupied Europe. The combination of accurate navigation from systems like GEE and pinpoint marking from Oboe significantly increased the effectiveness of RAF Bomber Command, reduced wasted effort, and marked a decisive step toward the modern concept of precision-guided bombing, even though the weapons themselves were still unguided free-fall bombs.