On this day in military history…

In February 1942 Singapore fell to Japanese forces after days of relentless bombing, shelling, and ground attacks that shattered both the city and the confidence of its defenders. The surrender on 15 February was the final act of a campaign that had begun weeks earlier with the rapid Japanese advance down the Malayan Peninsula, accompanied by air raids that steadily intensified as Singapore drew closer to the front line. What had once been promoted by the British as an impregnable fortress became, in a matter of days, an overcrowded, damaged city struggling to cope with fire, casualties, and fear.

Japanese bombing of Singapore had begun as early as December 1941, but by early February 1942 it became constant and devastating. Air raids struck docks, airfields, power stations, hospitals, and densely populated residential districts. Civilians sheltered in trenches, tunnels, and basements while fires burned unchecked in some areas and emergency services became overwhelmed. When Japanese troops crossed the Johor Strait on the night of 8 February, heavy artillery fire from the mainland and bombing from the air added to the destruction. Over the following days the fighting moved steadily southwards across the island, bringing combat closer to the city centre and worsening conditions for the civilian population.

The Allied forces defending Singapore were commanded by Arthur Percival, who had overall responsibility for British, Indian, Australian, and local troops. The civil governor of the Straits Settlements at the time was Shenton Thomas, but the surrender itself was a military decision taken by Percival and his senior officers. By 15 February the situation had become desperate. Japanese forces had captured key areas such as Bukit Timah, which held vital supply depots, and much of the island’s water infrastructure was either damaged or under enemy control. Fresh water was expected to run out within a day, food stocks were limited, and hospitals were overflowing with wounded civilians and soldiers. Continued resistance, particularly in the built-up areas of the city, was expected to lead to even greater civilian casualties and widespread destruction.

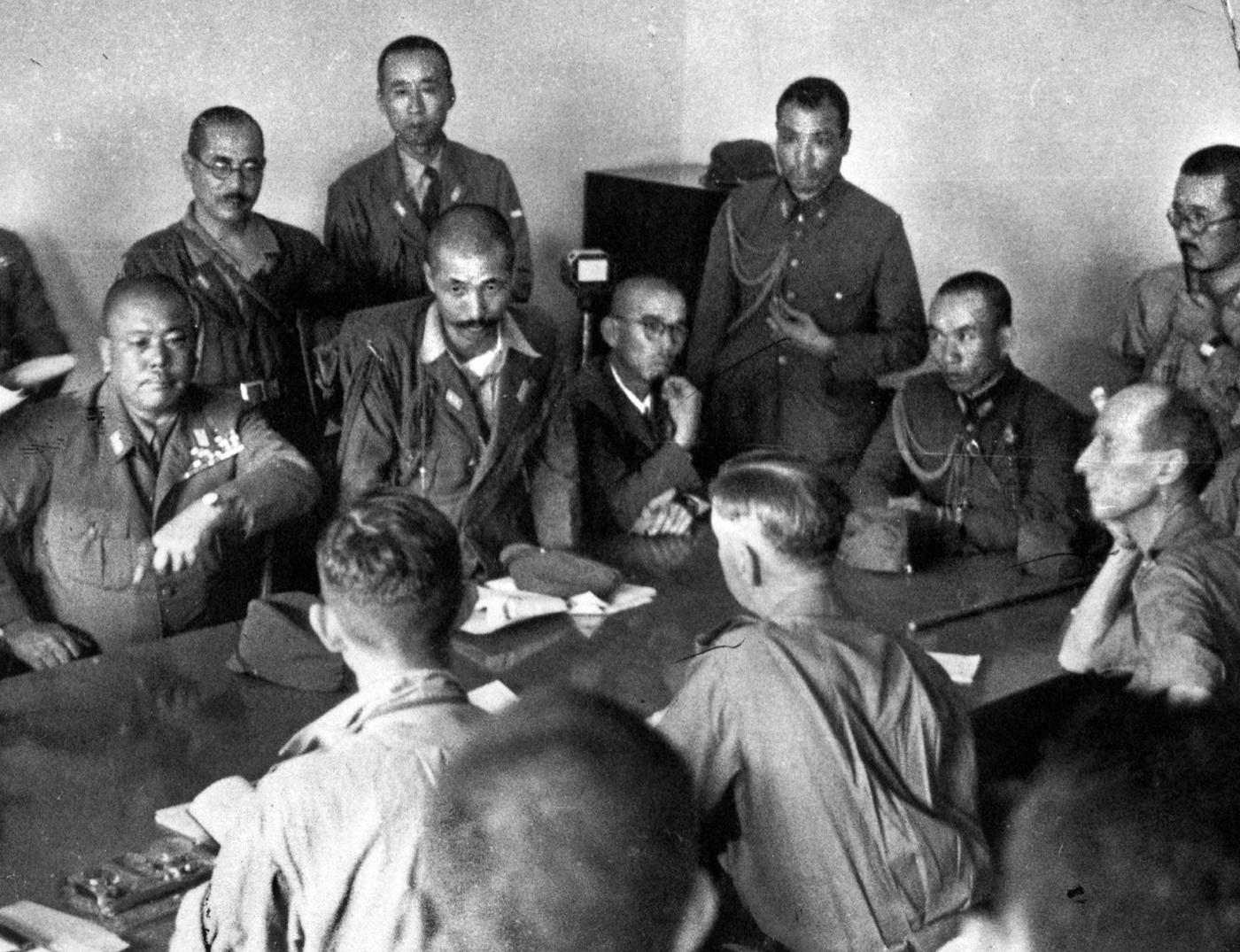

The decision to surrender was therefore made on the grounds that further fighting would achieve little militarily while causing enormous suffering to the civilian population. Percival later described it as the hardest decision of his life, taken not because troops lacked courage, but because the basic conditions required to sustain organised defence no longer existed. That afternoon, he travelled to the Ford Factory at Bukit Timah, where he formally surrendered Singapore to the Japanese commander.

The Japanese forces were led by Tomoyuki Yamashita, commander of the Japanese 25th Army. Yamashita’s troops on Singapore itself numbered roughly 30,000 to 36,000 men, drawn mainly from the 5th and 18th Divisions and the Imperial Guards Division. Although they were outnumbered by the total Allied garrison, Yamashita’s forces were well coordinated, highly mobile, and supported by effective artillery and air power. Japanese tactics emphasised speed, surprise, and pressure on key points, exploiting weaknesses in the defenders’ deployment and communications. Yamashita himself was concerned about his own supply situation and wanted to force a quick surrender rather than become bogged down in prolonged urban fighting.

During the bombing and fighting leading up to the surrender, civilian casualties were heavy. Thousands of civilians were killed or injured by air raids, artillery fire, and street fighting. Estimates vary, but by the time Singapore surrendered, around 7,000 civilians are believed to have died during the island battle, with many more wounded. Military casualties were also severe, and the surrender resulted in approximately 85,000 Allied troops becoming prisoners of war, making it one of the largest capitulations in British military history.

Once the surrender was signed, the fighting and bombing stopped abruptly. Many survivors later recalled the eerie silence that followed days of constant explosions and gunfire. However, the end of combat did not bring relief. Instead, it marked the beginning of a harsh Japanese occupation. Allied soldiers were marched into captivity, while civilians faced shortages of food, strict controls, and widespread fear. In the weeks and months that followed, Japanese authorities carried out brutal security operations and reprisals, adding further layers of trauma to a population already battered by war.

The fall of Singapore became a powerful symbol of imperial collapse and military miscalculation. British defences had been designed primarily to repel attacks from the sea, yet the Japanese came by land through Malaya, using speed and manoeuvre to outflank stronger positions. The defeat exposed serious weaknesses in planning, intelligence, and preparedness, and it had a profound psychological impact across Britain, its colonies, and the wider world.

Today, 15 February is officially commemorated in Singapore as Total Defence Day, sometimes informally referred to as Defence Day. The date is used as a reminder of the vulnerability revealed in 1942 and the importance of national preparedness, resilience, and shared responsibility for defence. It remains one of the most significant and sombre dates in Singapore’s history, marking not only military defeat, but the suffering of civilians and soldiers caught in one of the Second World War’s most dramatic and consequential collapses.