On this day in military history…

On 20 January 1942, in a quiet villa at Am Großen Wannsee 56–58 on the southwestern edge of Berlin, senior officials of Nazi Germany met for what became known as the Wannsee Conference, a pivotal moment in the bureaucratic coordination of the genocide that the regime called the “Final Solution of the Jewish Question.” By this point the mass murder of Jews was already under way in occupied Eastern Europe, but the meeting was designed to align ministries, clarify authority, and systematize deportation and killing across the whole of Europe under German control.

The conference was convened by Reinhard Heydrich, head of the Reich Main Security Office (RSHA) and one of Heinrich Himmler’s closest lieutenants. Heydrich had been tasked by Hermann Göring in July 1941 to prepare an overall plan for the “final solution,” and Wannsee was where he sought formal recognition of his leadership over the process and the cooperation of the civilian and party bureaucracies whose compliance was required. Fifteen men attended, representing the SS, the Nazi Party, and key government ministries. Alongside Heydrich were Adolf Eichmann, who organized the logistics of deportations; Heinrich Müller of the Gestapo; and Otto Hofmann from the SS Race and Settlement Office. The civilian ministries sent high-ranking officials such as Wilhelm Stuckart from the Interior Ministry, who had helped draft the Nuremberg racial laws; Josef Bühler from the General Government in occupied Poland; Roland Freisler from the Ministry of Justice; Martin Luther from the Foreign Office; and Erich Neumann from the Four Year Plan Office, among others. These were not fringe extremists but the administrative elite of the Third Reich.

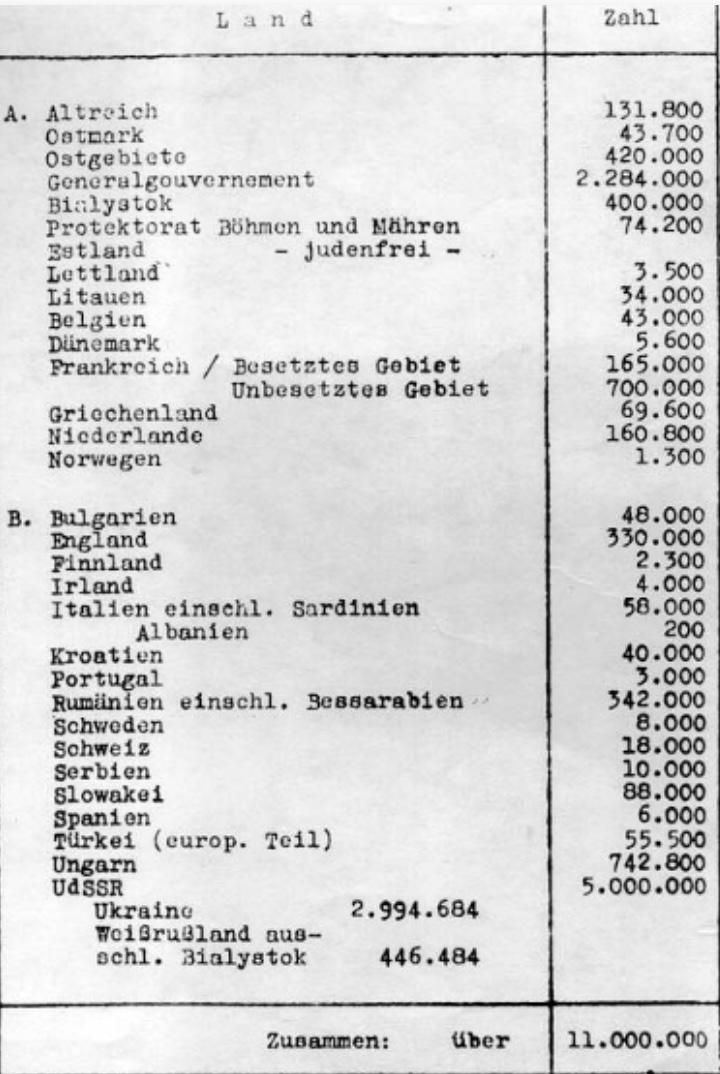

The discussion at Wannsee revolved around how to define who was to be targeted, how to handle people of mixed Jewish and non-Jewish ancestry, and how to organize the deportation of Jews from across Europe to killing centers in the East. Heydrich presented a chilling statistical overview listing approximately eleven million Jews in Europe, including those in countries not yet occupied by Germany, indicating the continental scope of the plan. The meeting assumed that Jews would be rounded up, transported eastward, and subjected to what the minutes euphemistically called “appropriate treatment,” a phrase that concealed forced labor followed by murder. Poland, already the site of mass shootings and the construction of extermination camps, was identified as the central killing ground.

What makes the Wannsee Conference especially significant is that it left behind a paper trail. Adolf Eichmann drafted the minutes, known as the Wannsee Protocol, which summarized the decisions in the bland, technical language of bureaucrats. Although the document avoided explicit references to gassing or shooting, its meaning is unmistakable when read in context. It spoke of “evacuation” of Jews to the East, of labor deployment under “suitable guidance,” and of a final “natural reduction” that would require “appropriate treatment” of any survivors. One surviving copy of the protocol, found after the war in the files of the German Foreign Office, became one of the most important pieces of documentary evidence proving that the Holocaust was not an accidental byproduct of war but a planned, coordinated policy at the highest levels of the Nazi state.

The meeting itself lasted about ninety minutes and took place over cognac and refreshments in a comfortable lakeside setting, a detail that underlines the terrifying normality with which mass murder was discussed. There were disagreements, particularly over the legal status of so-called Mischlinge, people with mixed Jewish and non-Jewish grandparents, and over whether forced sterilization or deportation should be applied to them. These debates show how deeply racial ideology and administrative calculation were intertwined, as officials weighed how to reconcile genocidal aims with existing laws and social realities.

By early 1942, extermination camps such as Chełmno were already operating, and others like Belzec, Sobibor, and Treblinka would soon follow as part of Operation Reinhard. Wannsee did not start the Holocaust, but it marked the moment when the machinery of the German state was formally harnessed to it in a unified way. The protocol produced there stands today as stark proof of intent, revealing how educated, professional men turned genocide into a matter of schedules, definitions, and transport lists. Remembering what happened on 20 January 1942 matters because it shows that one of history’s greatest crimes was not only driven by fanatical hatred, but also enabled by orderly desks, typed pages, and officials who chose to make murder their administrative task.