On this day in military history…

The Battle of Broodseinde, fought on October 4, 1917, was a major engagement during the First World War, forming part of the larger Third Battle of Ypres, commonly known as the Battle of Passchendaele. This clash occurred near the village of Zonnebeke in West Flanders, Belgium, and was a meticulously planned offensive by the British Empire against the German Army. It stands out as one of the most successful Allied attacks during the otherwise grim and attritional Ypres campaign.

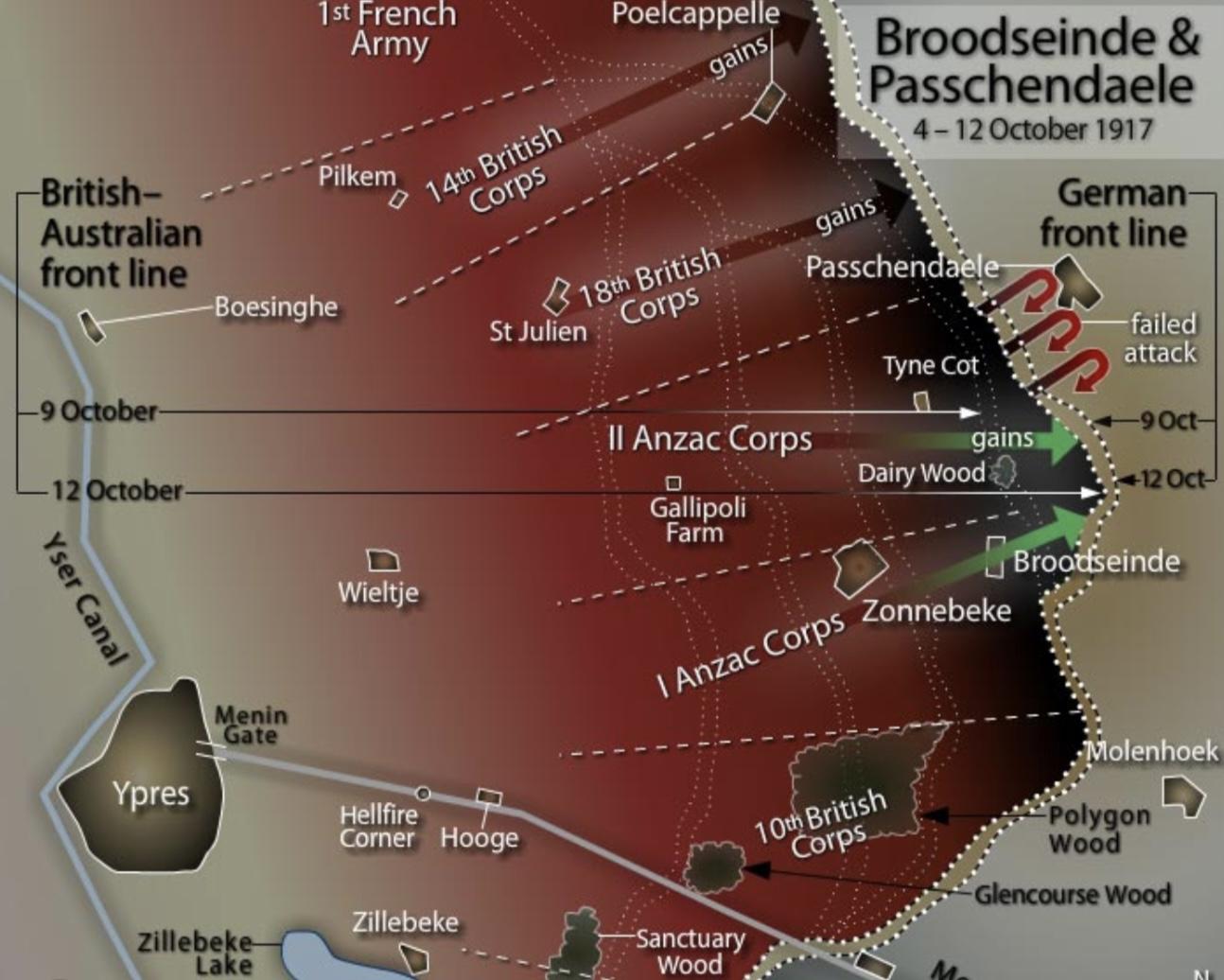

The battle was orchestrated by British General Herbert Plumer, commander of the British Second Army. Plumer was known for his methodical approach and careful planning, contrasting with the more aggressive tactics of other commanders. The opposing German forces were led by Crown Prince Rupprecht of Bavaria, who commanded Army Group Rupprecht, including the German Fourth Army under General Sixt von Armin. The British forces involved included units from the British Second and Fifth Armies, comprising British, Australian, and New Zealand troops. Notably, the Australian 1st, 2nd, and 3rd Divisions and the New Zealand Division played a key role in the assault.

Approximately twelve divisions of the British Empire forces participated in the attack, including six in the front line and several in support. Opposing them were elements of four German divisions, some of which were in the process of rotating into the front when the British attack struck. The total number of troops involved from the British side was estimated at around 100,000, while the German defenders numbered fewer, estimated at roughly 60,000.

Artillery played a pivotal role in the battle, as it did throughout the war on the Western Front. The British meticulously prepared an extensive artillery barrage that preceded the infantry advance. Over 1,000 guns were employed to deliver a creeping barrage, a tactic in which artillery fire moved forward in stages just ahead of the advancing infantry. This technique required precise coordination and had become a hallmark of British tactics by 1917. In addition to the field guns and howitzers used for the creeping barrage, heavy artillery targeted German strongpoints, trenches, and supply lines. German forces responded with their own artillery, but the surprise and intensity of the British bombardment significantly disrupted their defenses.

The significance of the Battle of Broodseinde lies in both its tactical success and its contribution to the overall Ypres offensive. British forces captured key ridges, including Broodseinde Ridge itself, which provided a commanding view of the surrounding terrain. The battle inflicted heavy casualties on the German forces and disrupted their defensive plans, particularly because the Germans were caught off guard during a scheduled relief and counterattack preparation. German troops were forming up for their own offensive, code-named "Gegenangriff," when the British struck, resulting in chaos and substantial German losses.

The outcome of the battle was a clear Allied victory. The British and dominion forces advanced up to 1,000 yards (900 meters) on a broad front and seized strategically vital ground. German casualties were estimated at over 30,000, while British and Commonwealth losses were also significant but slightly lower, estimated at around 20,000. The success at Broodseinde was a high point in the Passchendaele campaign and demonstrated the effectiveness of careful planning, concentrated artillery use, and combined arms coordination.

However, the victory did not come without cost or limitation. Following the battle, heavy rains returned to Flanders, turning the battlefield into a morass and severely hampering further operations. Despite the success at Broodseinde, the broader Passchendaele campaign dragged on for several more weeks, culminating in the capture of Passchendaele village in November at tremendous human cost.

The Battle of Broodseinde stands as a testament to the evolution of British military tactics during the First World War and highlights the capability of Allied forces to conduct coordinated and effective attacks under difficult conditions. It was a momentary triumph in a war characterized by stagnation and suffering, offering a rare glimpse of operational success in a campaign otherwise remembered for its mud and misery.