War Coffee

Throughout history, war has not only redrawn borders and shifted political powers, but it has also deeply altered everyday life for millions. One particularly telling example of wartime adaptation was the widespread use of coffee substitutes during major conflicts, especially World War I and World War II. As global trade collapsed under the pressure of naval blockades, rationing, and military priorities, access to real coffee—largely grown in tropical colonies or far-off nations—became severely limited. In response, countries turned to domestic ingenuity to create replacements that could replicate, at least in appearance, the daily ritual of a morning cup.

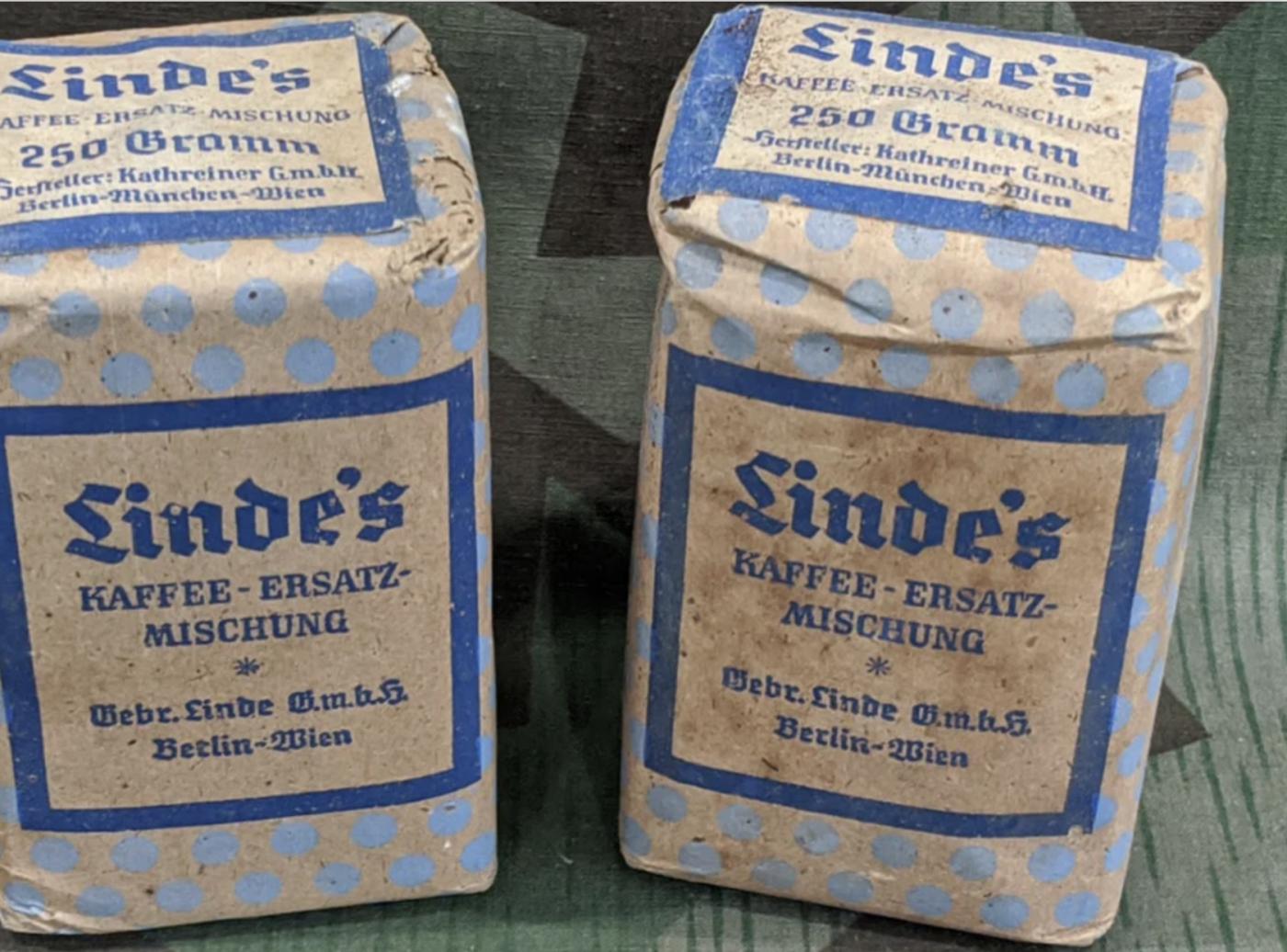

The use of substitute coffee was especially widespread in Germany, Austria, and occupied territories where trade isolation was most intense. Germany, which imported the majority of its coffee before the wars, became a leader in developing and promoting replacement beverages. With the term "ersatz" (German for "substitute") entering common use, German manufacturers began producing mixtures from locally available ingredients such as roasted chicory root, acorns, sugar beets, barley, malt, dandelion root, and even roasted fig seeds. These ingredients, once roasted and ground, could brew into a dark, bitter drink that visually resembled coffee but lacked its distinctive aroma, flavor complexity, and caffeine content.

One of the most prominent producers in Germany was Heinrich Franck Söhne, a company founded in 1828 in Ludwigsburg. Originally specializing in chicory-based products, the firm became a major supplier of coffee alternatives throughout both World Wars. Franck’s products, made largely from chicory and malt, were distributed widely across Germany and the occupied territories, even reaching front-line soldiers through army rations. The company’s preexisting expertise in non-coffee beverages made it a natural fit for large-scale production when war made real coffee scarce.

In Austria, similar production was led by companies like Kathreiner’s Malzkaffee-Fabrik, which had been producing malt coffee substitutes since the late 19th century. These firms shifted into high gear during the wars to meet the growing demand for caffeine-free alternatives. In France and the Netherlands, chicory-based drinks had already enjoyed some popularity as inexpensive alternatives even before the wars, so existing infrastructure allowed for increased output during the crisis years. French producers in regions like Nord-Pas-de-Calais, where chicory farming was concentrated, became important sources of raw material and processing.

Though Germany led in industrial-scale production, homemade versions also flourished in war-torn regions. Civilians, facing empty store shelves, roasted and ground their own blends from whatever ingredients were on hand. Acorns were commonly gathered, shelled, and roasted in household ovens. Dandelion roots were dug up and dried. These homemade preparations were often gritty, uneven, and bitter, but they provided some comfort to families deprived of imported luxuries.

In terms of taste, most agreed the substitutes were inferior. Chicory, while earthy and mildly bitter, could only vaguely mimic coffee’s depth. Acorn-based brews often had a burnt, woody flavor. Malted grain versions were sometimes described as watery or sour. Without caffeine, none of them provided the stimulant effect people craved. However, for many, especially in war zones, these hot beverages were better than nothing—a brief return to daily routine in a world turned upside down.

After the wars, most consumers quickly abandoned the imitations in favor of true coffee as trade routes reopened and global markets stabilized. However, some of these substitute drinks remained popular in certain regions. In Germany, Franck’s brand continued to sell malt- and chicory-based drinks well into the postwar decades. In France, chicory coffee remained a cultural staple, especially in northern regions. New Orleans in the United States, influenced by French settlers, famously continued the tradition with café au lait made from coffee mixed with roasted chicory.

Though originally born of necessity, these wartime beverages tell a larger story about adaptation and resilience. Far more than just a drink, the morning cup—no matter how far it strayed from the original—became a quiet act of normalcy, a psychological anchor amid upheaval. Whether produced by major firms like Heinrich Franck or crafted from foraged roots at home, these coffee substitutes reflect the determination to preserve daily rituals, even in the bleakest of times.