Historical history

On 24th October 1415, King Henry V of England led his army to a remarkable and unexpected victory against a much larger French force at the Battle of Agincourt, one of the most celebrated military triumphs in English history. This engagement took place during the Hundred Years’ War, a prolonged conflict between England and France over territorial claims and dynastic rights.

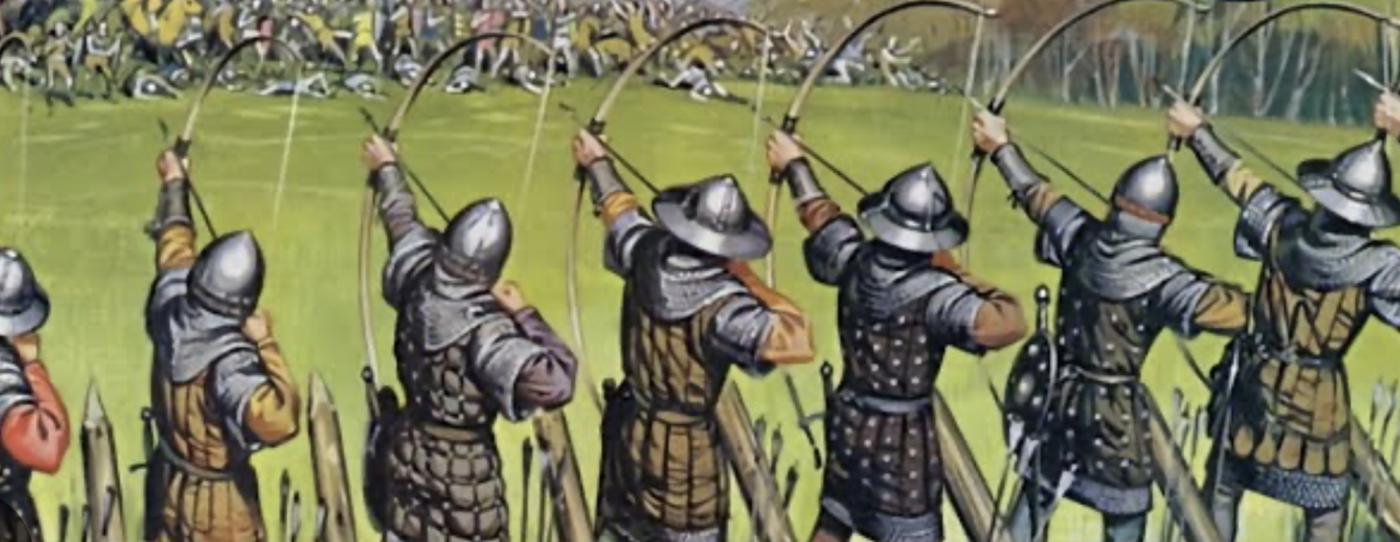

Henry’s army, though disciplined and determined, was severely depleted by the time they reached Agincourt. After a long and arduous campaign across northern France, the English forces numbered only around 6,000 men. Of these, approximately 5,000 were longbowmen—archers trained in the use of the English longbow, a devastating weapon capable of piercing armor at range. The remainder consisted of men-at-arms, heavily armored soldiers trained for close combat, often nobles and knights. The English army was exhausted, suffering from hunger, exposure, and illness after weeks of marching through hostile territory and sieging the town of Harfleur earlier in the campaign.

Opposing them was a much larger French force, estimated to number between 20,000 and 30,000 soldiers. The French army was composed mainly of knights and men-at-arms, with a smaller contingent of crossbowmen and archers. Many of these soldiers were members of the high nobility of France, confident in their superior numbers and status. The French command structure was less centralized than the English; nominally led by Charles d'Albret, the Constable of France, it also included several dukes and counts, each with their own followers and military ambitions. This lack of unity would prove disastrous in the battle to come.

The battlefield near Agincourt was a narrow strip of land flanked by dense woods on either side, which greatly limited the French army's ability to maneuver. The terrain had been soaked by recent rain, turning the fields to thick mud. This would severely hinder the heavily armored French knights as they advanced. Recognizing the advantages this geography offered, Henry arranged his forces in a tight defensive formation. His longbowmen were placed on the flanks behind wooden stakes planted in the ground to deter cavalry, while the men-at-arms held the center in a compact line.

The battle began with a provocation: the English archers unleashed a deadly hail of arrows into the French ranks, goading them into a charge. The French responded with a frontal assault, sending waves of heavily armored knights forward across the sodden field. As they struggled through the mud, they were met with continuous volleys from the English longbows, which tore through armor and disordered the French lines. Those who reached the English front ranks found themselves packed together, unable to fight effectively or retreat due to the press of men behind them.

What followed was a chaotic melee. The English men-at-arms, though fewer in number, fought with grim determination. Many French knights were killed or captured in the crush. A second French attack met the same fate, bogged down in the mud and cut down by arrows and swords. At one point, fearing a renewed assault on his camp and the risk of prisoners being rescued, Henry ordered the execution of many of the captured French nobles—a controversial act but one he considered necessary in the moment.

By the end of the day, the French had suffered a catastrophic defeat. Estimates suggest that between 6,000 and 10,000 French soldiers were killed, including many of the kingdom’s most prominent nobles. English casualties were remarkably light in comparison, possibly as few as 400. The scale of the French loss shocked all of Europe.

The victory at Agincourt had profound consequences. It boosted English morale and solidified Henry V’s reputation as a formidable military leader. Politically, it enhanced his position both at home and abroad, strengthening his claim to the French throne as he later negotiated the Treaty of Troyes, which named him heir to the French crown. For the French, the battle was a devastating blow, deepening internal divisions and exposing the weaknesses in their feudal military system.

Agincourt became a symbol of English resilience and tactical superiority. It demonstrated how discipline, terrain, and the effective use of technology—in this case, the longbow—could overcome superior numbers and traditional chivalric warfare. The battle would be immortalized in legend and literature, not least by William Shakespeare in his play Henry V, where the