Vinh window Vietnam

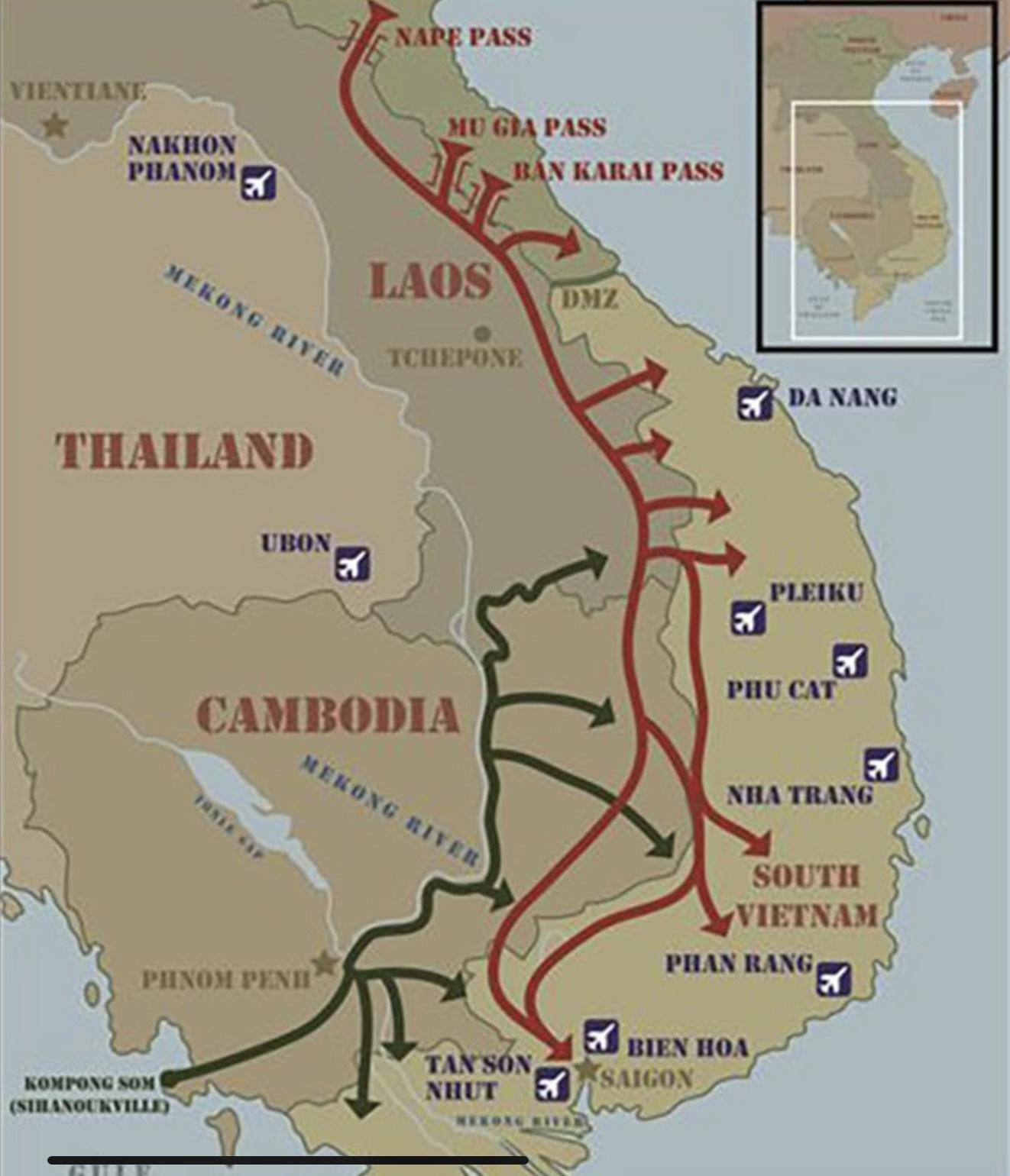

After the United States escalated its involvement in the Vietnam War in 1965, American intelligence agencies faced a daunting challenge: determining how many Communist troops and how much war material were infiltrating South Vietnam through the Hồ Chí Minh Trail. This extensive and complex network of roads, footpaths, and supply routes stretched from North Vietnam through the rugged terrain of Laos and Cambodia before entering South Vietnam. Despite overwhelming U.S. firepower and superior battlefield technology, the North Vietnamese and Việt Cộng continued to maintain a strong presence in the South. In fact, U.S. intelligence reports revealed an unsettling trend — the number of Communist forces operating in South Vietnam in 1967 was actually greater than in 1965 and 1966, despite heavy losses inflicted by American and South Vietnamese forces.

This discrepancy raised serious questions. How were Communist forces able to maintain and even grow their presence in South Vietnam despite suffering significant casualties? The answer, in part, lay in the North Vietnamese’s ability to move reinforcements and supplies down the Hồ Chí Minh Trail, often undetected and unimpeded. But understanding the full scope of this infiltration was extremely difficult for U.S. intelligence services. One major obstacle was the inability to effectively monitor and intercept the communications that coordinated this large-scale logistics operation. American cryptographers and reconnaissance teams knew that some form of central coordination had to exist—messages were being sent to organize movements, schedule deliveries, and deploy troops—but finding and accessing these communications proved elusive.

One of the reasons for this difficulty was the use of non-electronic communication methods by the North Vietnamese. They relied heavily on couriers who physically carried messages across borders and through jungle routes. This old-fashioned but effective system kept much of their command-and-control structure off the grid, rendering it invisible to the sophisticated signals interception technology deployed by the U.S. National Security Agency (NSA) and other military intelligence units. Furthermore, when electronic communications were used, they were often encrypted and transmitted in short, irregular bursts, making it difficult for American monitoring stations to catch them in time. The result was a significant intelligence gap: U.S. officials knew reinforcements and supplies were arriving, but not how, when, or in what numbers.

This intelligence blind spot persisted until a critical breakthrough occurred in October 1967. During a routine mission, a U.S. RC-130 aircraft participating in the Airborne Communications Reconnaissance Program (ACRP) was flying near the North Vietnamese city of Vinh. The aircraft was equipped with advanced radio monitoring and signal interception equipment and was tasked with scanning for enemy communications traffic. On this particular flight, the crew, which included skilled cryptologists, intercepted a stream of radio transmissions that seemed different from the usual tactical chatter. These messages were coming from Vinh—a known logistical hub located just north of the Laotian border and near the head of the Hồ Chí Minh Trail.

Upon analysis, it became clear that these transmissions were not ordinary battlefield communications. They were logistical orders: detailed, structured, and consistent, indicating the movement of troops, supplies, vehicles, and equipment. Cryptanalysts quickly realized they had uncovered a critical source of intelligence—Vinh was the nerve center for coordinating the flow of men and material into South Vietnam. The intercepted communications revealed what units were preparing to move, their approximate size, timelines for travel, and the types of supplies accompanying them. This was an unprecedented window into the inner workings of the North Vietnamese logistics network. From that point forward, this source of intelligence became known informally as the "Vinh Window."

The discovery of the Vinh Window marked a significant leap forward in the U.S. military’s ability to track Communist activities along the trail. Intelligence officers, linguists, and cryptographers at the NSA and other agencies began working around the clock to translate and analyze the intercepted messages. They cross-referenced this radio traffic with information gathered from other sources, including aerial surveillance, captured documents, and prisoner interrogations. For the first time, the United States had a reliable method of estimating how many troops were infiltrating South Vietnam at any given time and from where they were coming. This data improved the accuracy of troop estimates, informed military planning, and helped policymakers in Washington gain a clearer picture of the war’s scope.

However, the Vinh Window had its limitations. First and foremost, the intelligence gathered from Vinh was highly time-sensitive. The messages intercepted were often operational in nature, meaning they related to movements and decisions that were happening in real-time. If this intelligence wasn’t acted on within hours—or even minutes—it quickly became outdated. The fast pace of the war, combined with the bureaucratic hurdles of processing and disseminating information, meant that much of the intelligence was “perishable.” In practice, this meant that by the time analysts decoded a message and passed it along to commanders or strategic planners, the enemy units in question might have already moved or changed course.

Another challenge was the sheer volume of data being intercepted. The Vinh Window proved to be an incredibly rich source of information, but the U.S. intelligence community was not fully prepared for the task of managing it. Translating the coded Vietnamese radio transmissions into English, analyzing their significance, and delivering them to the right people in a timely manner required a massive and coordinated effort. Despite the expertise and dedication of those involved, bottlenecks occurred. Tactical commanders in the field sometimes received the intelligence too late to use it effectively. Meanwhile, strategic planners in Washington and Saigon were often overwhelmed with conflicting reports and delayed updates.

Moreover, while the Vinh Window gave the U.S. military a clearer understanding of how the North Vietnamese were operating, it did not provide a direct means of stopping the infiltration itself. The information could guide bombing campaigns or ambushes, but the Hồ Chí Minh Trail was vast, heavily camouflaged, and difficult to disrupt permanently. The North Vietnamese were highly skilled at repairing damage, rerouting traffic, and using the terrain to their advantage. Even with better intelligence, the U.S. struggled to significantly reduce the steady flow of troops and supplies that sustained the Communist war effort in the South.

In the end, the Vinh Window remained one of the most important intelligence discoveries of the Vietnam War, offering a rare glimpse into the enemy’s logistical operations. It enhanced U.S. understanding of the scale and coordination behind Communist troop movements and helped demystify how North Vietnam managed to wage a prolonged war despite heavy losses. However, its strategic value was constrained by the nature of the war itself. Intelligence, no matter how precise, could not easily overcome the geographic, political, and operational challenges that defined the Vietnam conflict.

The Vinh Window was kept secret for the duration of the war, known only to a limited group of analysts, commanders, and decision-makers. It was not widely acknowledged in public discussions or media coverage of the war effort, partly due to concerns over compromising the source and partly because it did not fundamentally alter the course of the conflict. Nevertheless, in retrospect, it stands as a powerful example of both the strengths and limits of intelligence work in modern warfare. It revealed the complexity of the enemy’s operations, the sophistication of U.S. technological capabilities, and the persistent difficulty of translating raw intelligence into battlefield success.