This is how World War 1 started

World War I, often called the “Great War,” began in 1914, but its causes had been building for decades. At the heart of the conflict were deep-rooted political, military, and ideological tensions between Europe's great powers. The main causes can be summarized by the concepts of militarism, alliances, imperialism, and nationalism—each playing a crucial role in the road to war.

Militarism refers to the belief in building up strong armed forces to prepare for war. In the early 20th century, European powers were locked in an arms race, particularly Germany and Britain, who were rapidly expanding their navies. France and Russia also invested heavily in their militaries, fearing German aggression. This build-up created a sense that war was not only inevitable but even desirable to demonstrate national strength.

The system of alliances also contributed heavily to the instability. By 1914, Europe was divided into two major alliance blocs: the Triple Entente (France, Russia, and Britain) and the Triple Alliance (Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Italy). These alliances were intended as deterrents—if one country was attacked, its allies would come to its defense—but instead, they created a dangerous domino effect, where a conflict between two nations could quickly escalate into a continent-wide war.

Imperialism further stoked rivalries, as European powers competed for colonies and influence around the world. Germany, a relatively new and rapidly industrializing nation, felt left out of the colonial spoils and sought to assert its place as a global power, threatening British and French interests in Africa and Asia.

Finally, nationalism—the belief in the superiority and independence of one's nation or ethnic group—was a powerful and sometimes destabilizing force. In multi-ethnic empires like Austria-Hungary and the Ottoman Empire, nationalist movements threatened the integrity of imperial rule. In the Balkans, nationalism was especially explosive, with Slavic groups like the Serbs pushing for independence or unification with other Slavic peoples.

All these forces—military buildup, entangled alliances, colonial rivalries, and ethnic nationalism—created a situation in which Europe was a powder keg, needing only a spark to ignite.

That spark came from the Balkans, a region in southeastern Europe known for its ethnic diversity and political instability. The area had been under the control of the weakening Ottoman Empire for centuries, but by the early 1900s, nationalist movements had begun to reshape the map. Serbia, in particular, had emerged as a rising power, promoting Pan-Slavism—a movement advocating the unity of all Slavic peoples under its leadership.

Austria-Hungary, a sprawling empire with many Slavic minorities, viewed Serbian nationalism as a direct threat. The two nations had clashed during the Balkan Wars, and tensions remained high. Bosnia and Herzegovina, a region with a large Slavic population, had been annexed by Austria-Hungary in 1908, angering Serbia and its ally, Russia.

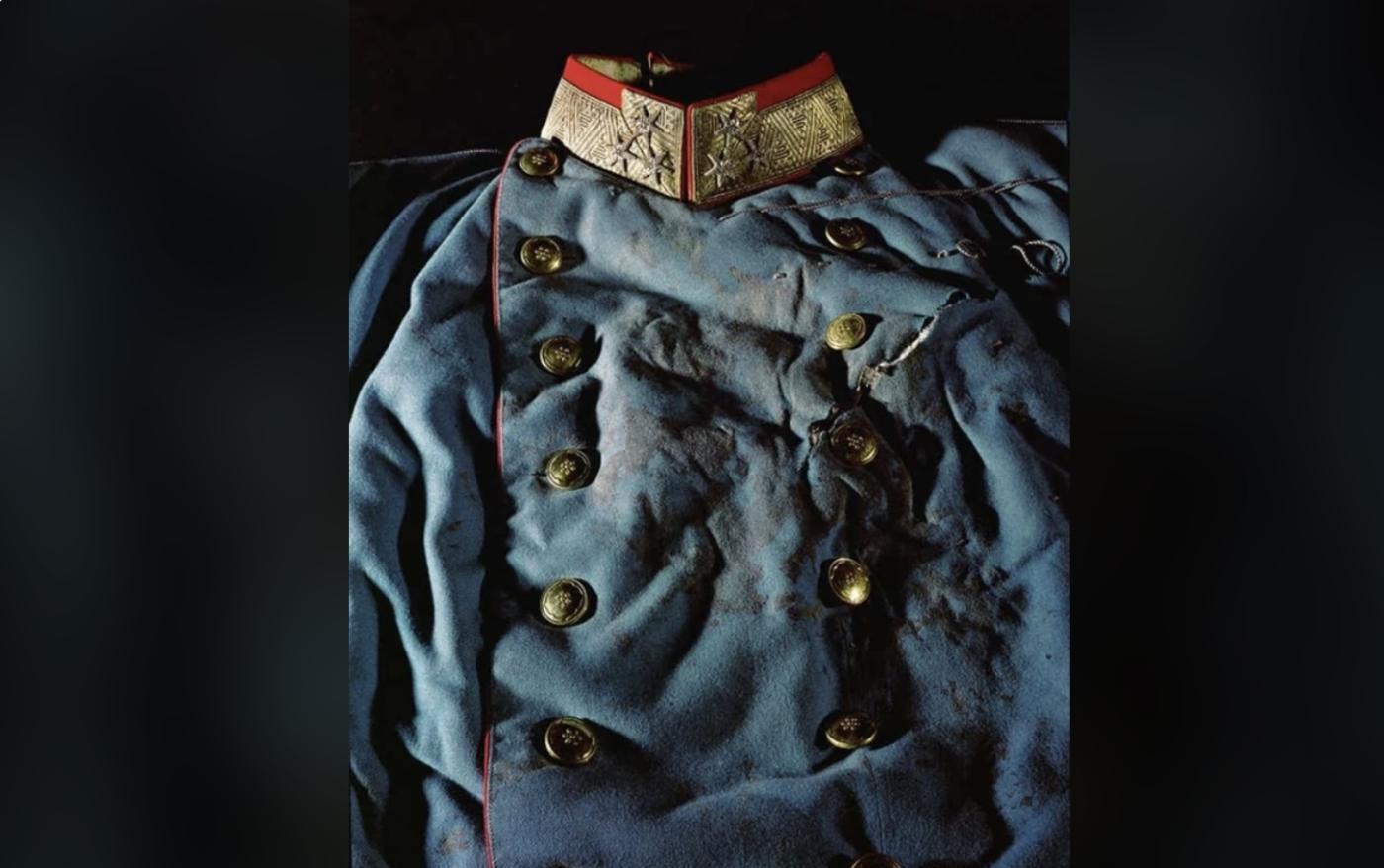

On June 28, 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, visited Sarajevo, the capital of Bosnia. His visit was seen as provocative by many Bosnian Serbs. That day, he and his wife, Sophie, were assassinated by Gavrilo Princip, a Bosnian Serb nationalist associated with the secret society Black Hand, which had ties to elements within the Serbian government.

The assassination shocked the world and set off a chain reaction. Austria-Hungary, enraged by the killing and determined to suppress Serbian nationalism, began preparing for retaliation. But the decision wasn’t made lightly—Vienna feared Russian intervention if Serbia was attacked. Thus, Austria-Hungary sought assurances from its powerful ally, Germany.

What followed the assassination is known as the July Crisis—a tense, month-long period of diplomacy, threats, and ultimatums that ultimately failed to prevent war.

On July 5, 1914, Germany gave Austria-Hungary a "blank cheque"—a promise of unconditional support. Encouraged by this, Austria-Hungary issued a harsh ultimatum to Serbia on July 23, demanding full cooperation with an investigation and allowing Austrian officials into Serbia. Although Serbia accepted most demands, it refused some that compromised its sovereignty.

Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia on July 28, 1914, exactly one month after the assassination. Russia, seeing itself as the protector of Slavic nations and allied with Serbia, began mobilizing its army. Germany, in turn, viewed Russian mobilization as a threat and declared war on Russia on August 1.

The web of alliances was now pulling countries into war. France, allied with Russia, prepared its own forces. Germany, anticipating a two-front war against France and Russia, activated the Schlieffen Plan, a military strategy that involved a rapid invasion of France through neutral Belgium.

Britain had pledged to defend Belgian neutrality under the Treaty of London (1839), and Germany's invasion of Belgium on August 4, 1914, was the final trigger. Britain declared war on Germany that same day.

By the first week of August, the major European powers were at war. What had begun as a regional conflict between Austria-Hungary and Serbia had spiraled into a full-scale global war.

Many historians have debated why diplomacy failed so catastrophically in 1914. Unlike later wars, the leaders involved did not necessarily want or plan for a total world war. Instead, many believed they could achieve quick victories or that their enemies would back down once faced with the threat of force.

One major reason for failure was the military planning and mobilization systems in place. For example, Germany's Schlieffen Plan required a precise timetable. Once mobilization began, there was little room to pause or change direction. Russia’s mobilization similarly forced German decisions. In essence, the machinery of war had become so rigid and complex that once it was set in motion, it was almost impossible to stop.

National pride and fear also played critical roles. Germany feared encirclement by France and Russia, while Austria-Hungary feared internal collapse from rising Slavic nationalism. Russia saw itself as the guardian of Slavic peoples, and France wanted to reclaim territories like Alsace-Lorraine lost to Germany in 1871.

Diplomatic communications were often slow, unclear, or influenced by outdated assumptions. Trust between nations was low, and many decision-makers acted based on worst-case scenarios. There were also powerful pressures from within: military leaders pushing for action, newspapers stirring public sentiment, and nationalist fervor drowning out caution.

In this environment, what might have been a limited Balkan conflict escalated into a massive war that engulfed Europe and eventually much of the world.

By late 1914, the war had spread beyond Europe. Japan joined the Allies and attacked German colonies in Asia. The Ottoman Empire entered the war on the side of the Central Powers. Fighting erupted in Africa, the Middle East, and even in the Pacific. What was initially expected to be a short conflict turned into a prolonged and bloody stalemate, particularly on the Western Front, where trench warfare led to horrific casualties.

The outbreak of World War I marked the collapse of the old world order. Monarchies that had ruled for centuries were shaken to their core. Entire generations were drawn into war, and empires began to crumble under the strain. The war’s end would see revolutions, redrawn borders, and an entirely new geopolitical landscape.

But it all began with deep-seated rivalries, unchecked militarism, and a single bullet in Sarajevo—a reminder that even the smallest spark can set off a fire when the world is full of dry tinder.