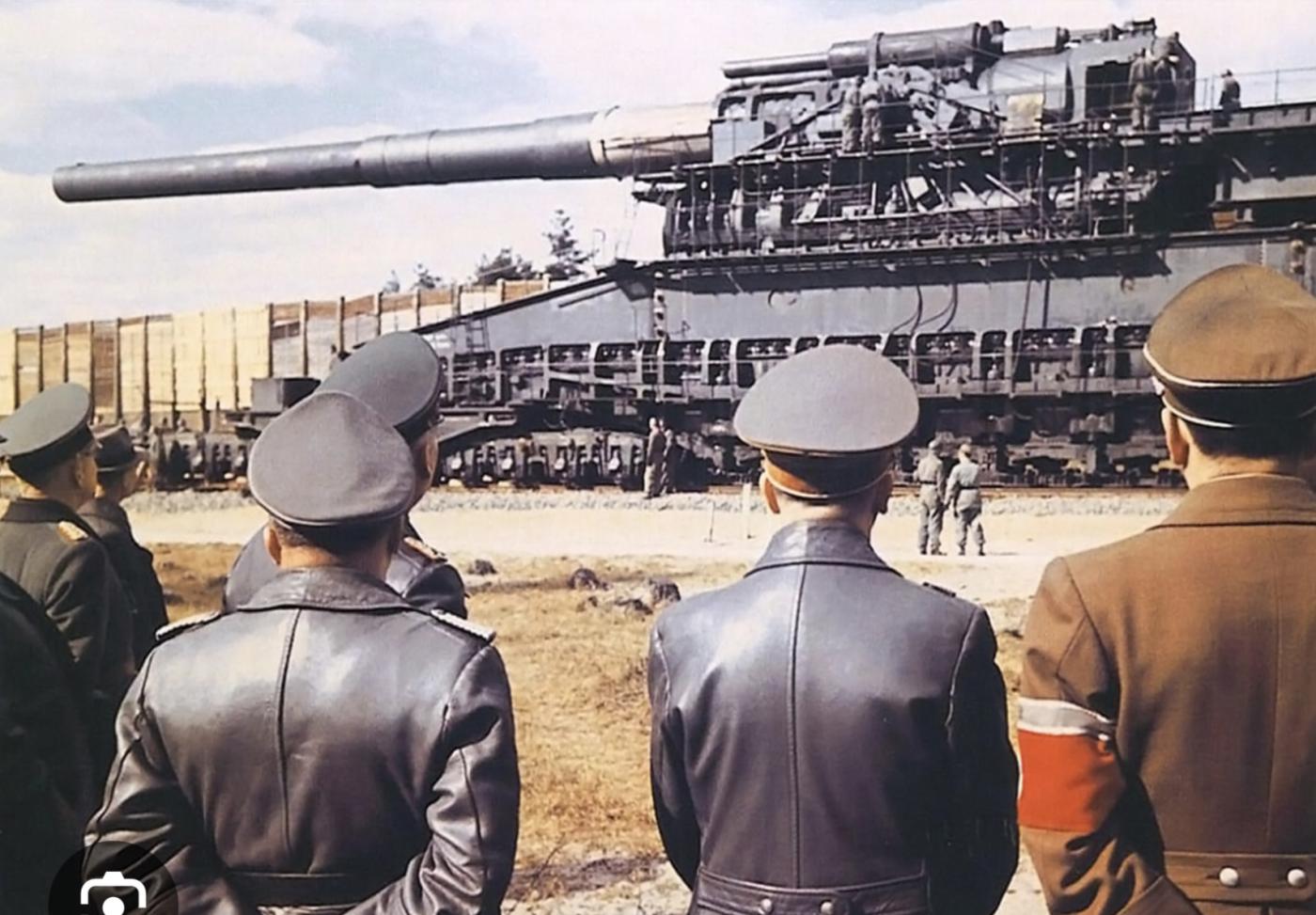

Gustav & Krupp railway artillery guns

During the first half of the 20th century, Germany invested heavily in the development of super-heavy artillery, particularly during the two World Wars. Among the most notable examples were the heavy railway guns produced by the industrial giant Friedrich Krupp AG and the enormous Schwerer Gustav, which represented the pinnacle of German engineering in railway artillery. These guns were not only feats of mechanical design but also psychological weapons meant to demonstrate military superiority and instill fear in opposing forces.

The German arms manufacturer Friedrich Krupp AG, headquartered in Essen, was responsible for designing and constructing most of Germany’s heavy railway artillery, including the famous "Big Bertha" guns used in World War I and, later, the Schwerer Gustav during World War II. Krupp’s experience in producing large-caliber naval and fortress guns made it the natural choice for engineering Germany’s largest land-based artillery. The concept of mounting large-caliber guns on rail carriages stemmed from the logistical difficulty of transporting and deploying such weapons in the field. Railways allowed these guns to be moved relatively quickly across long distances and positioned at strategic locations.

The Schwerer Gustav gun, designed in the late 1930s and completed in the early 1940s, was ordered by Adolf Hitler himself in anticipation of the assault on the French Maginot Line. Krupp’s chief engineer, Erich Müller, led the design team responsible for developing the Gustav. The project began with a formal commission in 1936, and after extensive trials and modifications, the prototype was finalised. The weapon was named “Gustav” after Gustav Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach, the head of the Krupp family business. The final version of the gun was known formally as “Schwerer Gustav” (Heavy Gustav).

The gun’s massive dimensions were unprecedented. Schwerer Gustav weighed approximately 1,350 tons and required a dedicated crew of 250 to 500 men to operate, with thousands more involved in its transport and support. It was mounted on a multi-axle twin-track rail system and required specially constructed tracks and infrastructure just to position and fire it. The main barrel was 80 centimeters in caliber (800 mm) and approximately 32.5 meters long. Each shell fired by Gustav weighed around 7 tons, and some armor-piercing variants could reach up to 7.1 tons. The explosive high-explosive shells used in combat weighed approximately 4.8 tons.

In terms of range, Schwerer Gustav could fire shells up to 47 kilometers (about 29 miles), depending on the ammunition type and firing angle. The primary high-explosive projectile had a range of about 29 to 38 kilometers, while the armor-piercing variant, which was heavier, could be fired at shorter ranges due to its mass. Gustav’s purpose was to destroy heavily fortified positions, such as concrete bunkers and underground ammunition depots. One of the most remarkable demonstrations of its firepower was during the 1942 siege of Sevastopol in the Soviet Union, where it was reported to have destroyed an underground ammunition magazine located 30 meters beneath reinforced concrete.

Despite its incredible size and engineering prowess, Schwerer Gustav was not a practical battlefield weapon. It took weeks to transport, assemble, and prepare for firing. The vulnerability of the gun to air attacks and the intense resources required for its deployment meant it was used only a handful of times. Alongside Gustav, a second similar gun, named Dora, was built and deployed briefly but saw even less action. A third gun, sometimes referred to in historical documents as Langer Gustav, was under construction but never completed before being destroyed near the end of the war.

Aside from Schwerer Gustav, the Krupp company also produced other railway artillery during both World Wars. In World War I, they manufactured the 420 mm “Big Bertha” howitzer, which, although technically not a railway gun in its earliest versions, later inspired the development of railway-mounted artillery due to logistical constraints. During World War II, various smaller-caliber guns, such as the K5(E) 283 mm railway gun, were also produced by Krupp. The K5(E) was far more mobile and practical in combat, with a barrel capable of firing shells up to 64 kilometers when using rocket-assisted projectiles like the “Peenemünder Pfeilgeschoss.” These guns were mounted on railway platforms and could be relocated rapidly compared to the colossal Schwerer Gustav.

The ammunition for Gustav was manufactured under tightly controlled conditions and consisted of several types. The high-explosive shells were designed to destroy large surface targets, while the armor-piercing variants were made to penetrate thick concrete and steel defenses. Each shell required its own powder charge, which was loaded separately into the breech behind the shell. The firing process involved careful calculation of atmospheric conditions, barrel temperature, and recoil compensation. Due to the barrel's massive size, the rifling wore out quickly and necessitated frequent maintenance and eventual replacement after a relatively small number of firings — estimates suggest that the barrel could fire only 300 rounds before needing to be replaced.

Ultimately, the legacy of the Krupp and Gustav railway guns lies more in their symbolic and technological significance than in their military effectiveness. They demonstrated Germany's industrial capability and engineering ambition but were largely outmoded by the rapid evolution of air power and mobile artillery. Nevertheless, these guns remain a striking example of the lengths to which nations went in the pursuit of military dominance during the early 20th century.