Geneva Accord North & South Vietnam

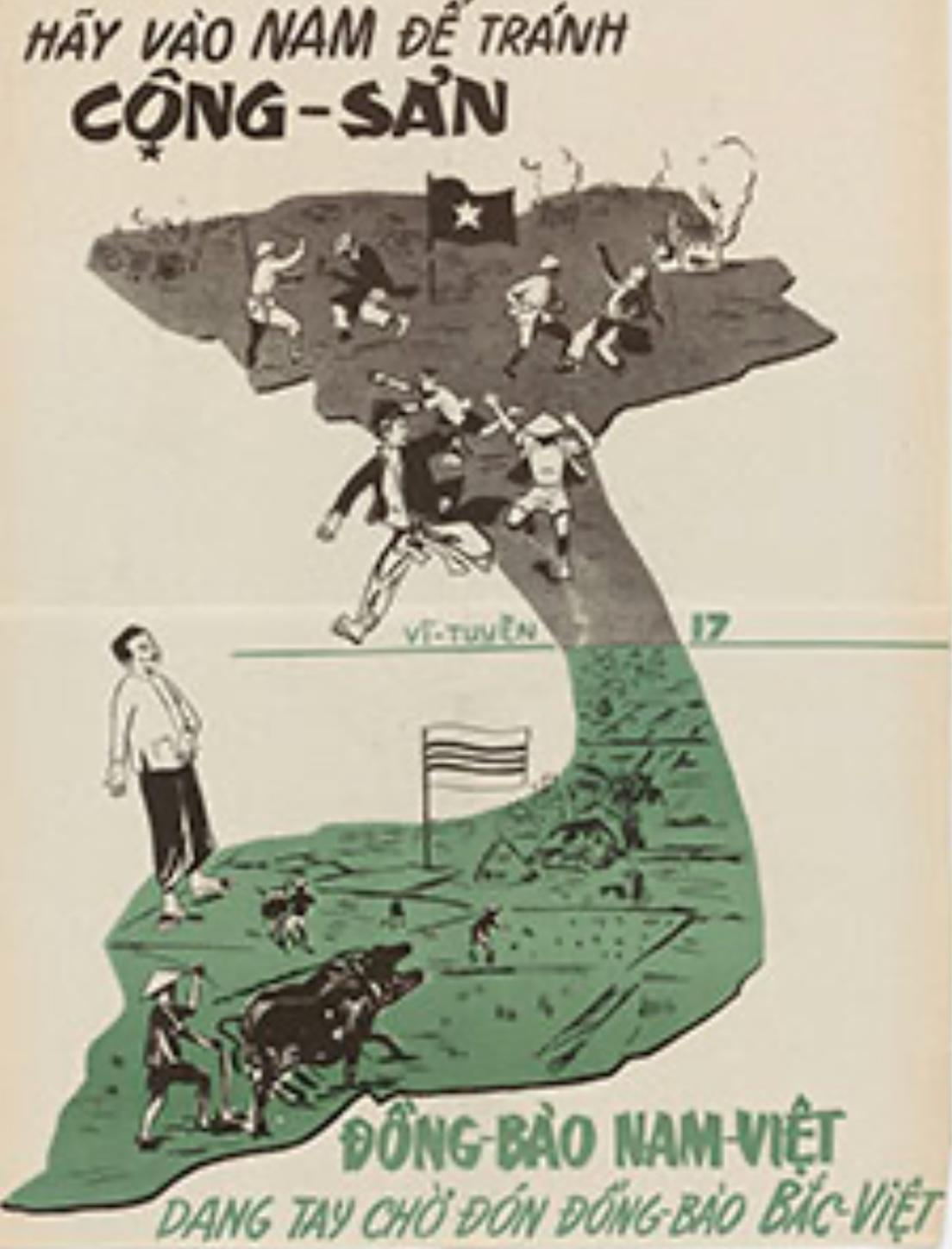

The Geneva Accord of 1954 marked a significant turning point in the history of Vietnam, bringing an end to years of conflict between French colonial forces and Vietnamese nationalist movements. One of the key provisions of the agreement was the temporary division of Vietnam at the 17th parallel, creating a northern and a southern zone. This division, however, was not intended to be permanent, and the accord laid out specific terms to allow for free movement between the two regions. The provision granting free movement was essential because it acknowledged the deep social, political, and familial connections that existed across the artificial boundary imposed by the agreement.

Under the accord, both the Democratic Republic of Vietnam in the North and the State of Vietnam in the South were to maintain a status quo until nationwide elections could be held to reunify the country. The free movement clause was designed to facilitate these future efforts by allowing citizens, goods, and information to cross the demarcation line without undue restriction. This provision recognized that, despite the political division, the Vietnamese people shared a common national identity and heritage, which necessitated continued interaction and exchange.

In practical terms, free movement between North and South Vietnam was intended to enable families divided by the new border to maintain contact, and for individuals to travel for work, education, or personal reasons. It was also meant to allow for the circulation of political ideas and to encourage the development of economic ties that could help ease tensions. The accord’s emphasis on freedom of movement was a reflection of the hopes for a peaceful, democratic reunification process through political dialogue and elections.

However, the reality of free movement was more complicated. Although the Geneva Accord explicitly allowed for this freedom, the two newly formed governments had differing interpretations and political motivations that affected how movement was regulated on the ground. In the North, the communist government under Ho Chi Minh viewed the provision as a way to facilitate the safe return of refugees and supporters from the South, aiming to strengthen its base. In contrast, the southern government, backed by Western powers, was more cautious and sought to limit infiltration by communist sympathizers, often imposing restrictions under the guise of security concerns.

Despite these challenges, the initial months following the Geneva Accord saw a considerable flow of people between the two zones. Tens of thousands of refugees, mostly from the North, moved south in what was described as a massive migration fueled by fears of communist repression and hopes for better opportunities. This movement was facilitated by international organizations and military forces overseeing the ceasefire, who worked to ensure safe passage and humanitarian aid. The accord’s promise of free movement was thus partially realized, serving as a lifeline for many seeking to escape uncertain futures.

Over time, however, political and military tensions escalated, and the ideal of unrestricted movement began to erode. Both sides tightened border controls and increasingly viewed the movement of people as a potential threat to their authority. This led to the establishment of checkpoints, travel permits, and other bureaucratic obstacles that undermined the spirit of the Geneva Accord. The initial hope that free movement would promote reunification through democratic processes gave way to entrenched division and conflict, ultimately culminating in the Vietnam War.