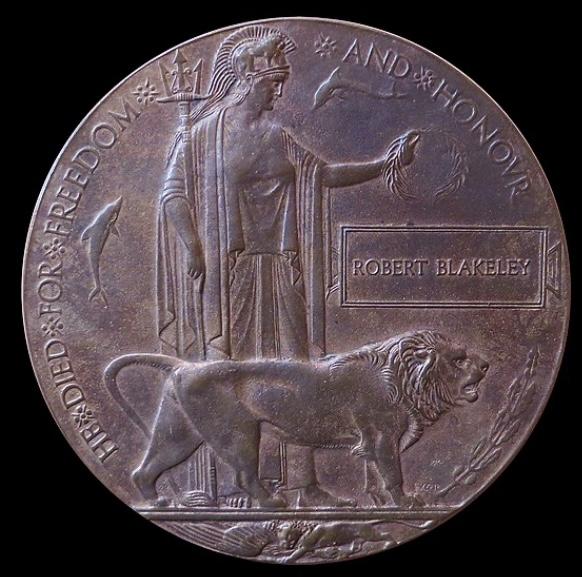

Death Penny

The Bronze Memorial Plaque, often called the “Dead Man’s Penny” because of its size and color, was a deeply symbolic item sent to the families of British and Empire service members who died during World War I. Made of cast bronze and nearly five inches across, each plaque bore the name of the person who died, offering a solemn and lasting tribute. For many families, especially those without a grave to visit, the plaque became one of the only physical reminders of their loved one’s sacrifice.

In 1917, while the war was still raging, the British Ministry of Pensions proposed creating a memorial plaque that would be sent to the next of kin of every service member who had died as a result of the war. A public competition was launched to design it, offering a prize of £250. The winning entry came from Edward Carter Preston, a British sculptor, whose design would go on to be reproduced more than a million times.

Production began in 1919 at a factory in Acton, London, and later expanded to Woolwich Arsenal due to the enormous number required. Over 1.3 million plaques were made, including some 600 for women. To produce all of them, about 450 tons of bronze were used. The sheer volume of material reflects the staggering number of lives lost, and the immense scale of the effort to remember them individually.

Each plaque was cast with the full name of the deceased, but no military rank or decorations. This was a deliberate choice, meant to show that all who served and died were equal in sacrifice, regardless of status or position.

The design is full of symbolism. It shows Britannia, the female personification of Britain, standing with a trident in one hand and a laurel wreath in the other, representing both strength and honor. A lion stands at her feet, symbolizing courage and the power of the British Empire. Two dolphins appear on either side of Britannia, alluding to Britain’s naval strength. There is also a smaller image of a lion attacking a German eagle, representing victory over the enemy. Around the edge of the plaque is the inscription “He died for freedom and honour,” which was changed to “She died for freedom and honour” in the plaques issued for women. Each person’s name was included in a rectangular panel, cast directly into the bronze, giving each piece a unique and personal identity.

Along with the plaque, families received a memorial scroll printed on high-quality paper with the name of the deceased in calligraphy, and a letter from King George V offering the nation’s condolences. These plaques were often framed or displayed in the home and became treasured reminders of the people they represented.

Today, these memorial plaques are valued historical artifacts. They can be found in museums, war memorial exhibitions, and private collections. Many are still held by descendants of the people they commemorate. More than a hundred years after the war, the plaques remain a powerful reminder of the human cost of conflict. The 450 tons of bronze used to make them speaks not only to the industrial effort behind their creation, but also to the vast scale of sacrifice during the First World War. Each plaque represents a life lost, a family changed forever, and a promise that those who died for their country would not be forgotten.