Brutal Japanese

Brutal Treatment of Allied POWs by Japanese Forces

During World War II, thousands of Allied troops captured by Japanese forces endured one of the darkest and most horrifying experiences of the war. Held in prison camps across Southeast Asia and the Pacific, these men faced unspeakable conditions — starvation, disease, overwork, and brutal punishment were all part of their daily lives.

The prisoners, mostly from Britain, Australia, the United States, and the Netherlands, were captured after fierce battles and surrender in places like Singapore, the Philippines, and Java. Once in Japanese hands, they were stripped of any rights, herded into overcrowded camps, and subjected to a regime that operated without mercy or restraint.

Life inside the camps was hellish. Food was minimal — a thin broth, sometimes a handful of rice, rarely anything more. Men who once marched proudly in uniform were reduced to skeletal figures, their bodies failing from the constant malnutrition and unrelenting labor. Medical supplies were almost nonexistent. Wounds festered. Disease spread unchecked. Dysentery, malaria, and cholera were common, killing prisoners in droves.

Forced labor was relentless. POWs were put to work building railroads, airstrips, and fortifications for the Japanese war machine. Perhaps the most infamous of these was the Burma-Thailand Railway, where men worked barefoot through the jungle, beaten with bamboo canes and rifle butts if they faltered. They hauled heavy timbers and stones in blazing heat, often working sixteen hours a day or more, collapsing where they stood from exhaustion.

Brutality by the guards was constant. Beatings were administered for the smallest perceived slights — not bowing correctly, not working fast enough, or simply being in the wrong place at the wrong time. Guards often used wooden poles, metal rods, or whatever else was on hand to deliver savage punishment. Prisoners were tied to posts in the sun without food or water. Others were locked in small cages barely large enough to sit, kept there for days in their own filth.

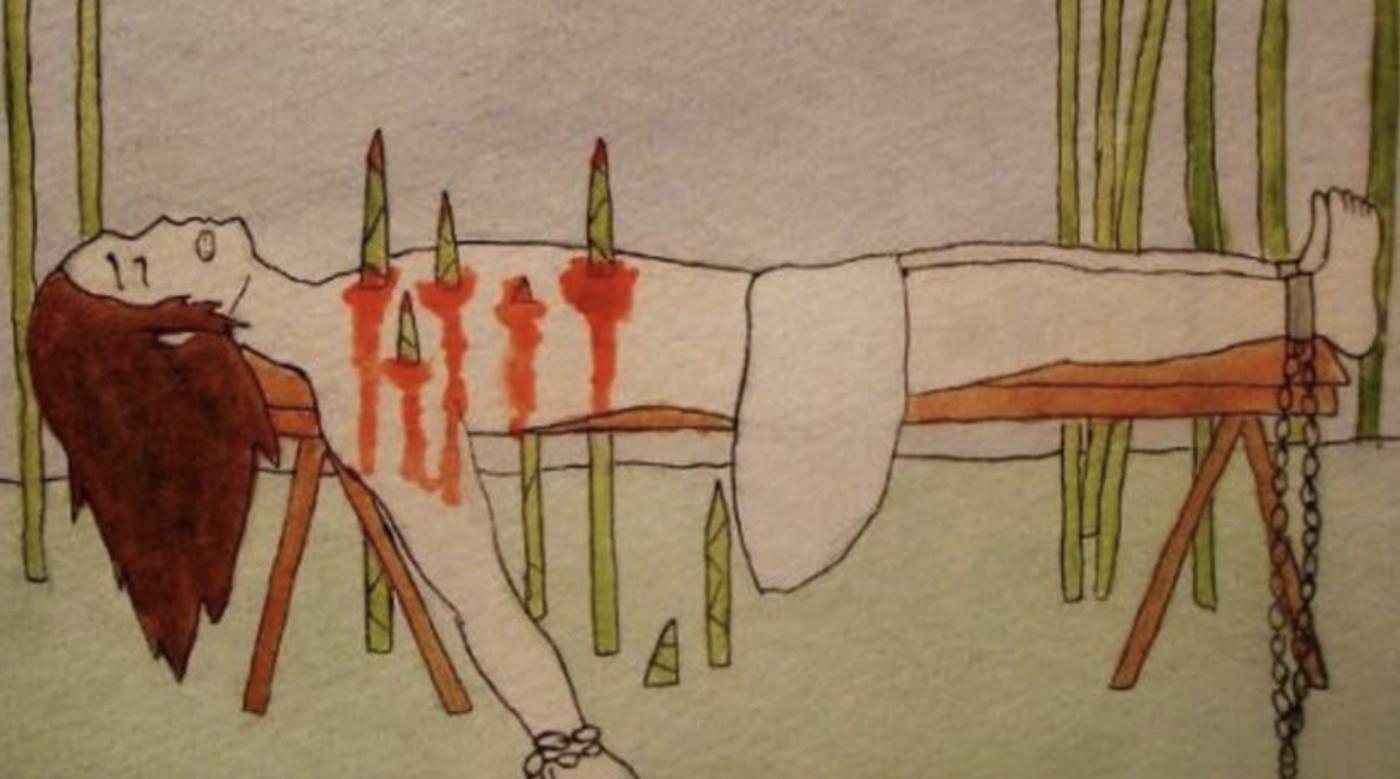

Among the most chilling and cruel forms of torture attributed to some Japanese captors was the so-called bamboo torture. Prisoners were tied face-up above a patch of young bamboo, their backs pressed close to the shoots. Over time — sometimes days — the sharp, fast-growing bamboo would grow upward, piercing through the flesh. Bamboo can grow several inches per day under the right conditions, and the sharpness of the young shoots meant they could push through skin and muscle with steady force. Whether this was done as punishment or execution, it served as a terrifying example of how nature itself was weaponised in acts of psychological and physical torture.

Psychological torment was also deeply embedded in the daily life of prisoners. Some were forced to beat or betray each other under threat of execution. Others were subjected to mock executions — blindfolded, marched out, and made to kneel while a bayonet was pressed to their necks, only to be laughed at and kicked back into line. A constant, gnawing fear hung over the camps. Any day could bring death, and no one knew when or how it would come.

Execution without trial was common. Suspected escapees were decapitated. Groups of prisoners might be chosen at random for reprisal killings. In some of the most horrifying documented cases, Japanese soldiers practiced cannibalism, consuming the bodies of executed or dying prisoners. These incidents, while rare, reflect the complete breakdown of humanity in the most brutal theatres of the war.

By the time the war ended, tens of thousands of Allied POWs had died in Japanese captivity. The death rate in these camps was more than six times higher than those held by the Germans. Survivors returned home haunted — malnourished, disease-ridden, and emotionally shattered.

Their suffering remains a stark reminder of the horrors of war and the capacity for cruelty when international rules are ignored and human dignity is abandoned. Their stories — of suffering, resilience, and survival — deserve to be told and remembered.